One of the things we spend a lot of time studying are Alaska’s fiscal policy baselines. There are several.

On the revenue side, the Department of Revenue (DOR) regularly publishes two long term (10-year) revenue forecasts every year (Spring and Fall).

As a regular part of its financial reports, the Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation (PFC) monthly publishes similar, long term (10-year) projections of Permanent Fund statutory net income – used to calculate the statutory Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) – and the Percent of Market Value (POMV) transfers projected to be made annually from the Fund.

On the spending side, the administration’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) annually publishes a long term (10-year) revenue and spending forecast in connection with the governor’s proposed budget.

In response to the governor’s budget, the Legislature’s Legislative Finance Division (LegFin) then publishes two long term (10-year) baselines of its own, one reflecting projected spending based on “current policy” derived from on the previous year’s budget and the other reflecting projected spending based on “current law.” From those they then run a number of scenarios over the course of any given legislative session as requested by the chairs of the Finance Committees.

For our part, we also prepare and publish periodic budget baselines which we use for various ongoing analyses and charts during and between legislative sessions, particularly our weekly “Goldilocks” updates.

The various baselines differ on both the revenue and spending sides.

DOR publishes its own forecasts of traditional revenues (oil revenues plus existing taxes and fees), but adopts the PFC’s with respect to POMV and PFD levels. In its annual 10-year forecast, OMB takes its revenue number from DOR’s annual Fall forecast.

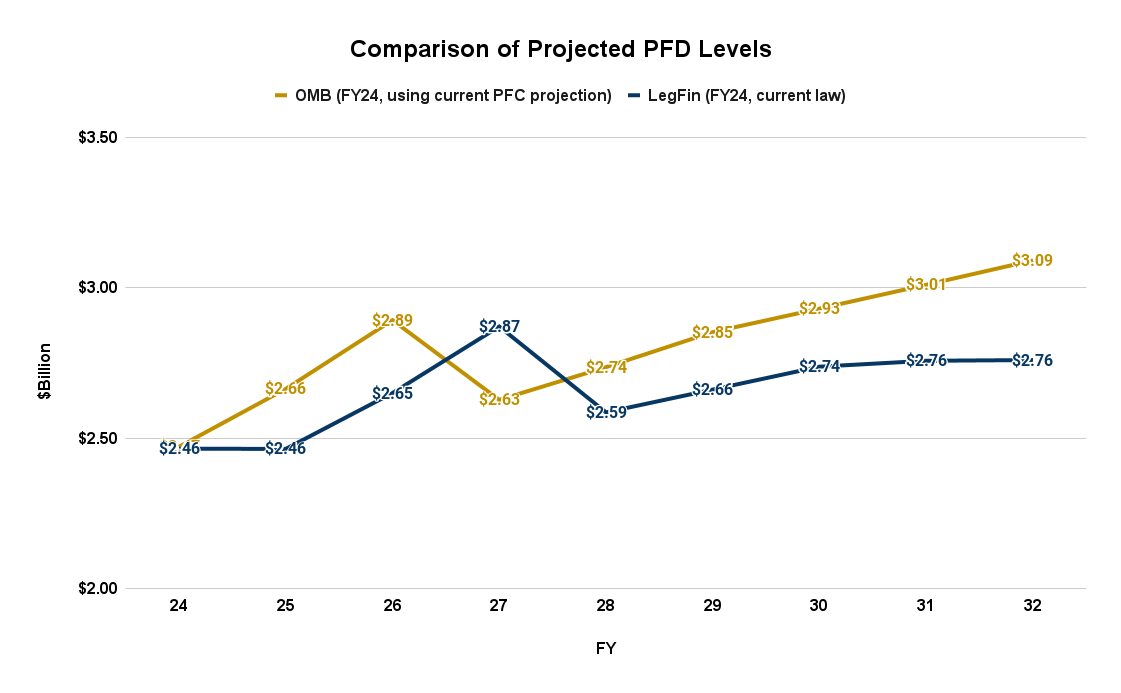

LegFin uses DOR’s forecast of traditional revenues, but uses different rates of return than the PFC (for reasons we don’t fully understand) in preparing its own forecasts of POMV and PFD levels. Here’s the difference in PFD projections between the two:

Like DOR, we use the PFC’s projections of both POMV and PFD levels, but differ by updating our forecast of traditional revenues more frequently to reflect ongoing changes in the oil futures market.

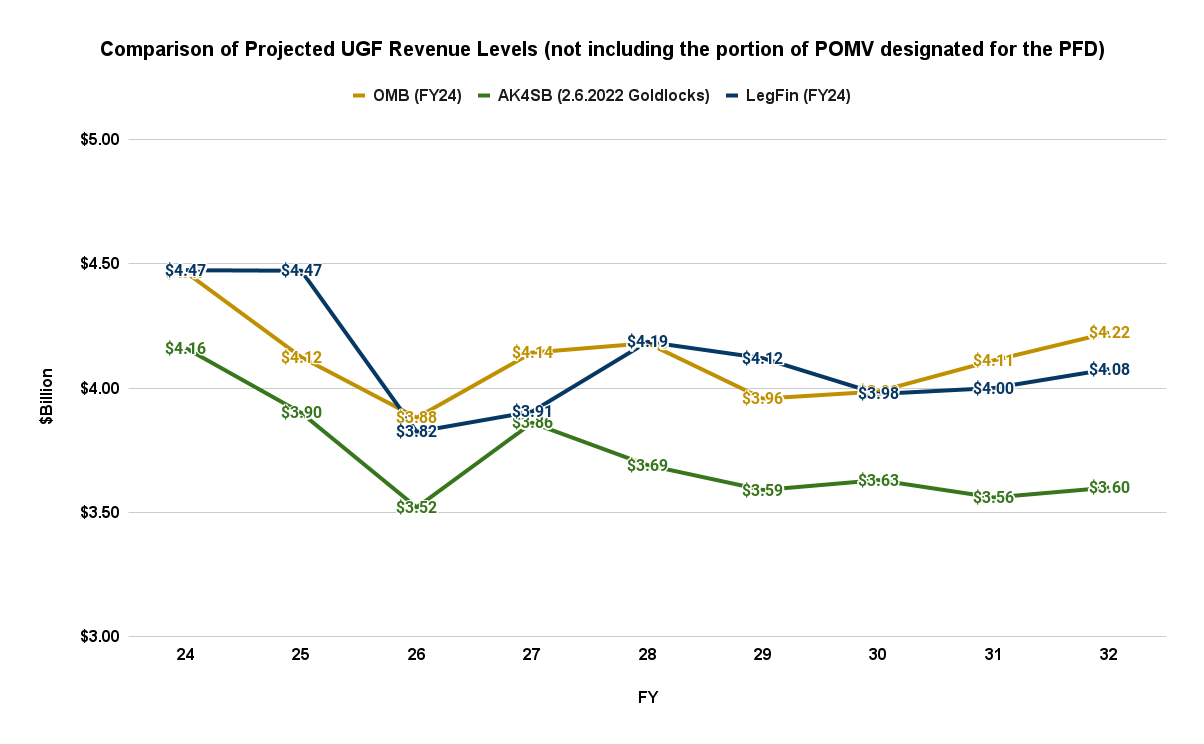

As of today, here’s the difference in revenue projections among the three sources over the upcoming “10-year” (really, 9) period.

It’s something of a hodgepodge. Because of their different views of Permanent Fund returns, and thus, POMV and PFD levels, LegFin is higher than DOR & OMB some years and lower in others. Due to the impact of declines in oil futures on projections of traditional revenues, we recently have become consistently lower on the revenue side than both.

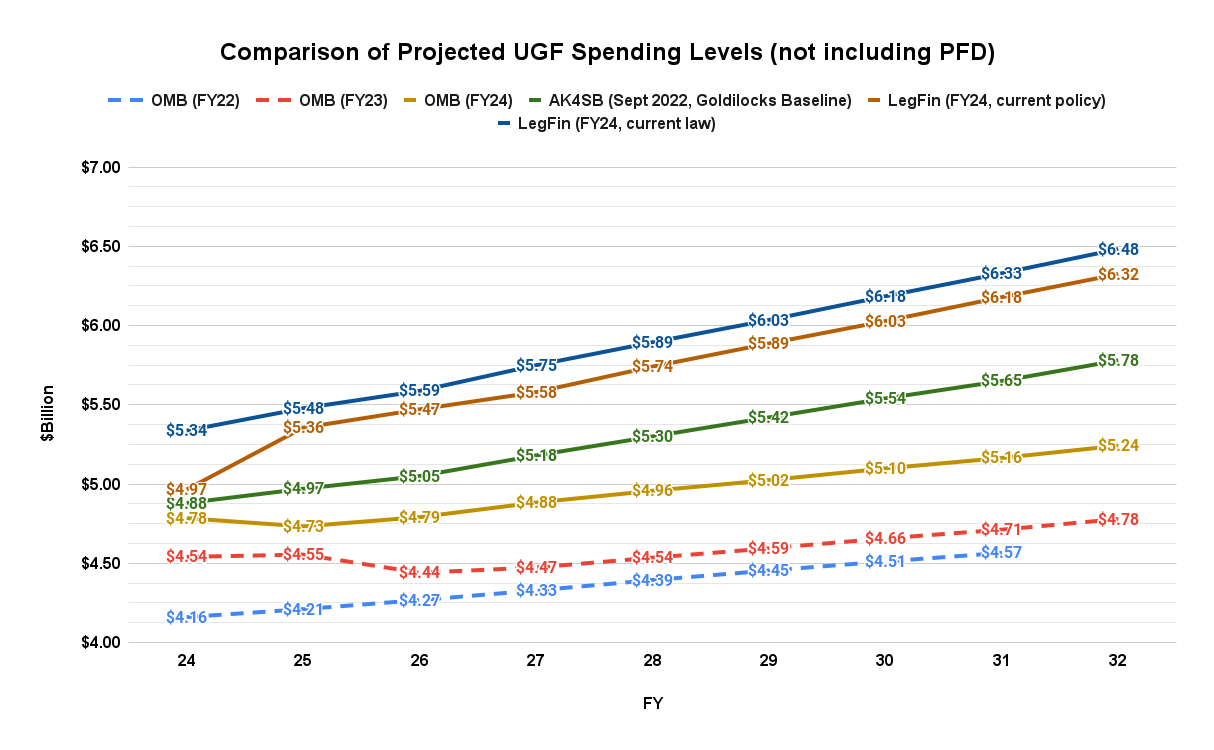

The differences are even greater on the spending side. There, LegFin’s projections over the projection period substantially exceed both those made by OMB and us. Here’s the comparison (we have included the projected spending levels included for the period in OMB’s FY22 and FY23 10-year plans as well to show the progression in the Dunleavy administration’s thinking over time):

Three of the four current forecasts (OMB, LegFin current policy and us) start near the same level in FY24. Because it fully funds all statewide items to their statutory level, however, LegFin’s “current law” baseline starts substantially higher.

After a significant jump in the current policy baseline in FY25, LegFin’s two baselines stay relatively close thereafter, separated in the out years (FY29 and beyond) by only roughly $150 million (2.5%). Ours stays in the middle, running below LegFin’s in the out years by roughly $500 million (10%), and above OMB’s by roughly the same amount.

While up significantly from the FY22 and FY23 projections, OMB’s FY24 projection remains relatively low, rising at an annual compound rate of only 1.16% over the period.

By comparison, LegFin’s two baselines rise at annual compound rates of 2.45% (current law) and 3.05% (current policy) and ours rises at an annual compound rate of 2.2%.

There are two significant differences in approach between the various baselines that largely explain their different trajectories. The first is the difference between the current policy and current law approaches. Both OMB’s and ours essentially use the current policy approach, setting the funding throughout the period of some spending categories below the levels assumed by LegFin in its current law, and after FY24, current policy approaches.

The second significant difference in approach is the treatment of inflation. Though at slightly different rates, both LegFin and we consistently adjust spending levels throughout the period to reflect currently projected inflation levels.

OMB, on the other hand, does not. For reasons we discussed – and heavily criticized – in a previous column, OMB intentionally uses an annual adjustment factor that is significantly below currently projected inflation levels.

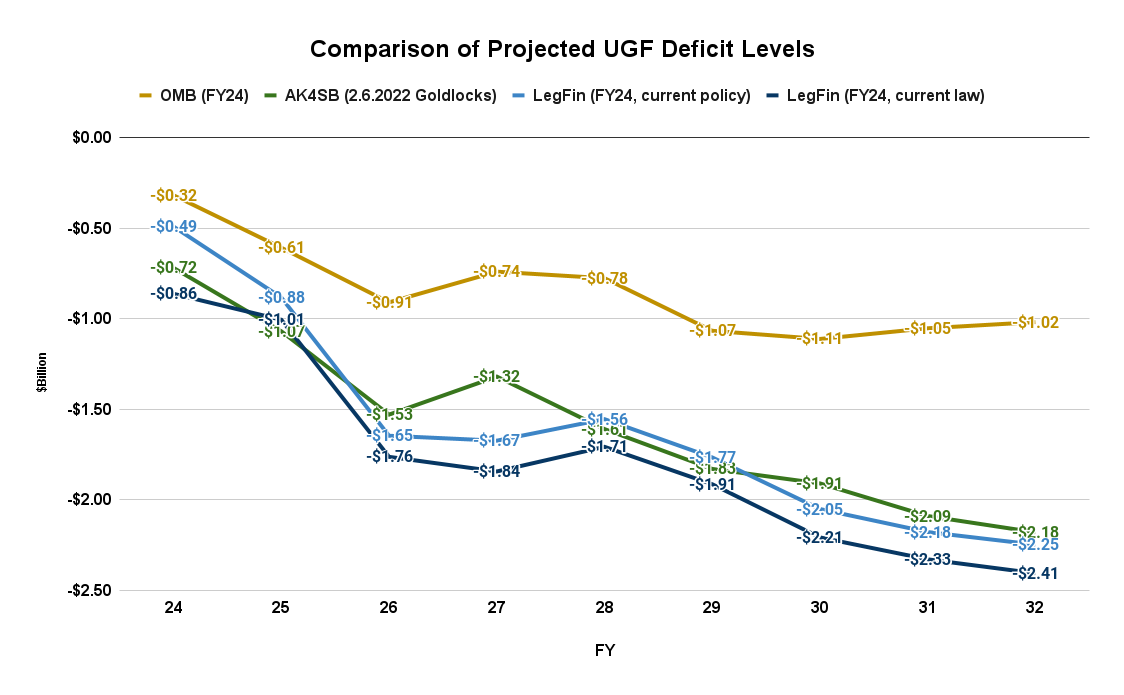

Because of differences in both the revenue and spending baselines, understandably there are significant differences also in the baseline deficits each of the sources project.

To be clear, all three forecasts – LegFin’s, OMB’s and ours – are projecting annual deficits starting soon and rising significantly over the forecast period. None are projecting a future in which the state is able to avoid the need for additional revenues.

There are significant differences in the levels, however. Here is a comparison of the deficit levels projected by each:

While OMB’s forecast projects a deficit, by comparison to the others it paints a relatively rosy picture, holding out-year deficit levels to roughly $1 billion. That provides Governor Mike Dunleavy (R – Alaska) some cover when he then projects balancing the budget solely with the “hundreds of millions of dollars” in future carbon management fees he anticipates the state will receive in future years.

On the other hand, although we arrive there in significantly different ways, we and LegFin jointly see a substantially different future unfolding.

LegFin’s “current law” baseline sees annual deficits growing to $2.41 billion – 37% of spending – by FY32. By the same year, annual deficits under LegFin’s “current policy” approach reach $2.25 billion – 35% of spending – and we project annual deficits at $2.18 billion – 38% of spending.

The outlook is not that much better if you focus only on the intermediate term – where things are in five years (FY28).

OMB projects a deficit at that point of $780 million, 16% of spending. We and LegFIn, on the other hand, project significantly larger levels. LegFin projects a “current policy” deficit of $1.56 billion (27% of spending) and a “current law” deficit of $1.71 billion (28% of spending). We project a deficit of $1.61 billion (30% of spending).

In short, all three forecasts – both LegFin’s “current policy” and “current law” projections and ours – project deficits at levels approaching double those projected by the Dunleavy administration in both the intermediate and longer term. Not even at their most extreme does the governor’s forecasted “carbon management” fees cover deficits at those levels.

So, what’s the takeaway from all that?

First, at a surface level, it’s that there is no universal fiscal “baseline” of where Alaska is headed. LegFin can’t even agree with the administration (DOR and OMB) on projected revenue levels, much less spending. And we think all of them are using stale oil numbers.

When someone says “here’s the state’s fiscal baseline,” they are talking about their version of the baseline – built around their views of the future – not some universal truth.

But below that surface, there’s a second takeaway, and that is the future of Alaska – and Alaska families – becomes increasingly bleak if we don’t adopt a solid fiscal policy very soon that both develops equitable sources of new revenues and creates real incentives for slowing the rate of spending growth (in our view, by engaging the top 20% in the result).

Although it may not have intended to do so, LegFin’s recent Overview of the Governor’s (FY24] Request provides a very helpful “rule of thumb” about Alaska’s fiscal situation that is applicable here. It concludes that, in Alaska, raising $900 million in additional revenue through a personal tax is the equivalent of an overall effective personal tax rate of 3% adjusted gross income (AGI).

That level happens to be close to the average level of PFD cuts made over the period from FY17 – FY23, and means that, overall, Alaska has experienced roughly a 3% average effective personal tax rate over the past six years. Of course, almost all of that burden has fallen on middle and lower income Alaska families. Those in the top 20% have contributed only a trivial share and non-residents have contributed zero.

But overall, the average effective personal tax rate Alaskan families have experienced is about 3% of AGI.

On its current trajectory, however, by only five years from now (FY28) Alaska will need an effective personal tax rate (of whatever kind – head taxes, sales taxes, progressive income taxes) of somewhere between 5 and 6% of AGI to balance the budget.

And that effective personal tax rate will continue to grow to 7 to 8% of AGI by FY32.

As we have explained in a previous column, if distributed equitably Alaska can relatively easily continue to accommodate an effective personal tax rate of 3% of AGI.

Doubling that to effective personal tax rates of 6% and 8% of AGI, however, raises significant issues.

To avoid that we need to develop mechanisms to equitably distribute the burden we have now, and to significantly slow down the rate of continued growth going forward.

In one way or another, that’s what all of the baselines – regardless of which one you happen to choose – are telling us.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.