While most eyes are focused on next week’s election, ours increasingly are turning to mid-December, when the then-governor is required to submit his proposed initial FY24 budget and related 10-year plan to the Legislature.

Of course, the election will have a significant impact on what is submitted then, but there are certain things that we believe should be included both in the proposed budget and plan regardless of who is elected.

Here are the Top 4:

- Be honest with Alaskans about the state’s fiscal situation. This seems like a no-brainer – and it should be – but if the past is any indication, it’s not.

There are two basic parts to every budget – revenue and spending. In Alaska, unrestricted general fund (UGF) revenue is composed basically of oil and investment revenues.

While the projection of oil revenues used to be somewhat opaque (and as a result, manipulable), through the use of publicly available futures prices and professional production estimates the system has become much more transparent and understandable over the past few years.

That certainly does not mean it’s always an accurate projection of the future. As we’ve seen over this year alone, futures prices can be high (or low) during the budget cycle and then, as market conditions change, flip to the opposite after. A seemingly comfortable budget at one point can become problematic as the year wears on.

But that doesn’t mean the forecasted revenues aren’t honest at the time the forecast is made. By using a transparent process, Alaskans should have confidence that any administration is making the best projection it can of the situation the state is facing as of the time the projection is made.

The same can’t always be said for the spending side, however. Over the past few years the spending numbers in both the initial budget and 10-year plan have seemed artificial, crammed into whatever the revenue number is so as to avoid showing significant deficits. This passage from last year’s 10-year plan discussing inflation suggests that’s not unintentional:

One method for projecting future expenditure changes in non-formula State spending is to use a projection of a common inflation metric, like the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is a measure of the cost of goods purchased by the normal consumer published by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. An analysis of historical trends, however, does not indicate a strong correlation between CPI and State government spending and find that expenditure trends are more closely aligned with the availability of revenues and the policies of incumbent administrations. Given the Governor’s commitment to fiscal prudence, and projections indicating adequate but constrained future revenues, OMB uses a 1.5 percent inflation rate for non-formula programs.

The consequence is that the budgets consistently have understated projected future spending – and thus, deficit – levels, enabling administrations and legislatures alike to avoid confronting the need to develop mid- and long-range plans for dealing with them. The result has been a series of short-term fiscal band-aids, based on the (objectively unjustified) rationalization that the future will be better.

The coming budget and 10-year plan should be honest with Alaskans from the beginning about both the state’s near and long-term fiscal situation and outlook. That means, among other things, using a realistic inflation rate, not one derived by reverse engineering a number to avoid showing the future deficits the state unavoidably faces on its current path.

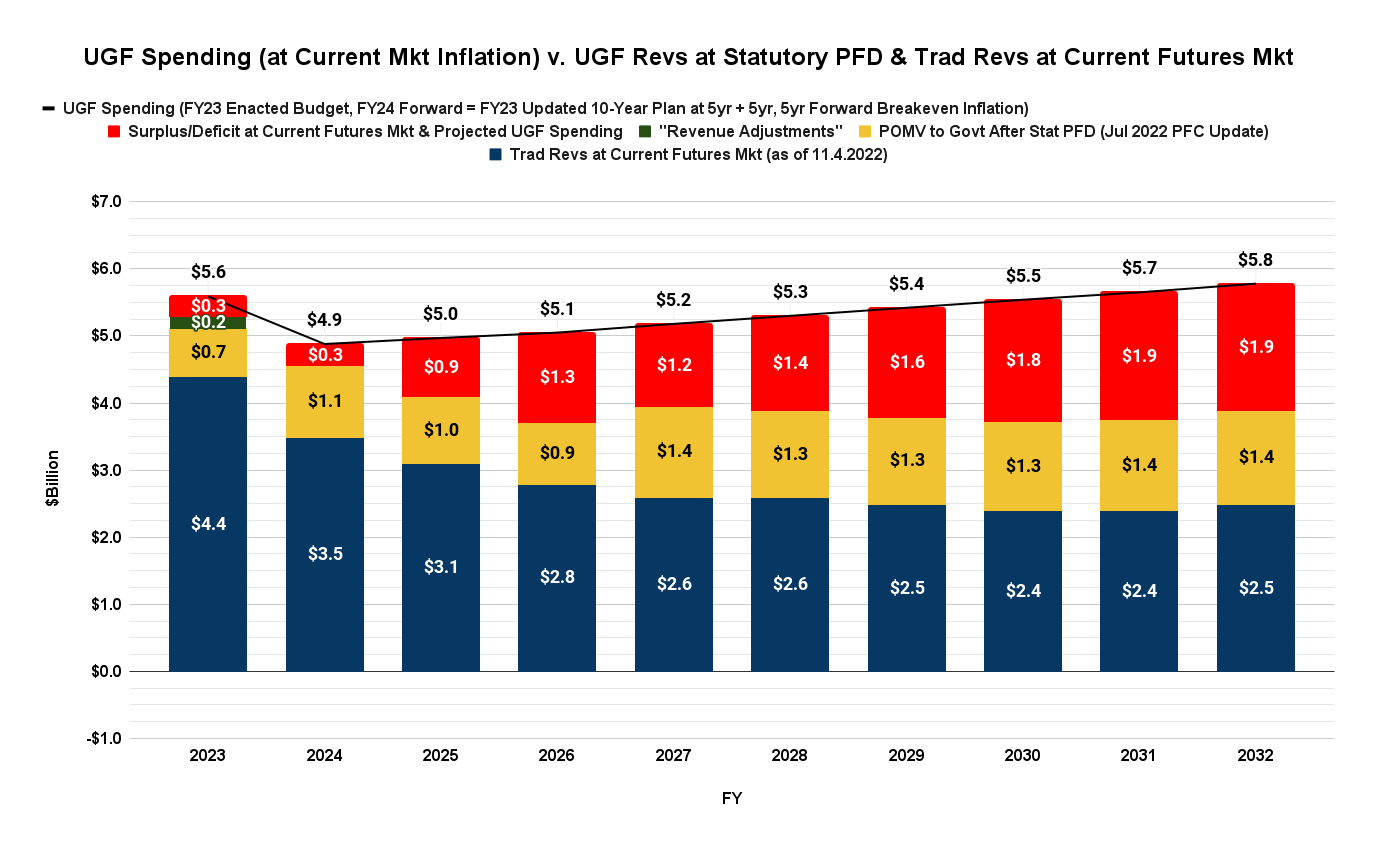

Based on current futures prices and our most recent update of projected spending levels using the baseline resulting from this year’s legislative session and current inflation rates as projected in the financial markets, here’s our view of the current 10-year outlook (red above the line are deficits). It’s not pretty.

2. Include a Constitutional Budget Reserve (CBR) payback as an expense. During this year’s campaign all candidates have talked to varying degrees about the need to position Alaska for future generations. Yet, there has been deafening silence on one of the most important – if not the most important – issue that will affect those generations.

That issue is the level of the “rainy day” savings accounts this generation is leaving for them.

Over the past decade Alaska’s current generation has drained roughly $18.5 billion, combined, from the Statutory and Constitutional Budget Reserves, along with diverting (taxing) another $3 billion from the statutory Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD), in an ongoing effort to cushion itself against the impact of the changing fiscal environment.

The result is that the fiscal cupboards are being left largely bare for future generations. As it stands now, rather than having the same ability from which this generation has benefitted to cushion any fiscal blows they may face, future generations are being left largely without any backup. The result is that as they hit fiscal bumps – and they will – they won’t have the same fiscal insurance from which this generation has benefitted; instead, they will have to pay immediately to cover the impacts, likely through heavy taxes, largely from the first dollar.

Some argue that the situation will fix itself over time without the need for any conscious effort – that over time this generation will apply the “surpluses” it receives from high oil prices to rebuild the savings accounts to be left for future generations.

One only has to look at this year’s legislative session, however, to realize that’s a fantasy. In a year of near record overall revenues, the Dunleavy administration and Legislature managed to set aside, in the context of the overall amounts due, a small, indeed what most would consider paltry, contribution.

It’s fine that this generation has drawn on the state’s rainy day accounts. That’s their purpose, to help cushion the transition from one fiscal condition to another.

But by draining the accounts without refilling them, this generation is in the process of leaving future generations holding the bag. Like any debtor in arrears, this generation – beginning with the administration – should adopt a firm payment schedule to catch up. We made some suggestions on how in a previous column. We hope to see those – or other ideas that achieve the same objective – in the upcoming and future budgets.

3. Calculate oil revenues for budget purposes on a 10-year average (or 5 year, with sideboards). As we look back over the decades, one of the biggest reasons for Alaska’s fiscal challenges has been the use of projections for the upcoming year’s oil price as the basis for the annual budget. In some years – like where the current year appears headed – reality has failed to live up to the projections, leaving the budget overextended.

Even when accurate, because oil prices (and with them, revenues) go up some years and down in others, developing a steady budget backed up by steady revenues largely has been impossible. Spending programs developed during periods of strong oil revenues – such as the state’s three independent university systems – have proven significantly problematic when oil revenues have retreated.

The implementation of percent of market value (POMV) draws from the Permanent Fund are designed to steady the revenue stream, and they have to some degree, but they only go so far. Even in low oil price years, oil revenues still remain a significant share of overall revenues and, as a consequence as projections bounce up and down from year to year, they still create an uneven revenue base that fails to support the programs built on them in strong years.

As it has with the use of Permanent Fund earnings through the design of the POMV program, Alaska state government would greatly benefit from adopting an approach that consistently steadies the flow of oil revenues into the budget process. Doing so would create a firmer fiscal base on which to develop long-term, sustainable programs.

In a recent column we looked at a couple of ways to do that. Both used the same general sort of averaging approach as currently used for both POMV draws and the calculation of the statutory PFD.

One was to use, for budgeting purposes in any given year, the average level of oil and other traditional revenues realized over the preceding ten years. The second was to use the average realized over the preceding five years, but subject to “sideboards” that limited the change up or down to no more than 15% from the previous year.

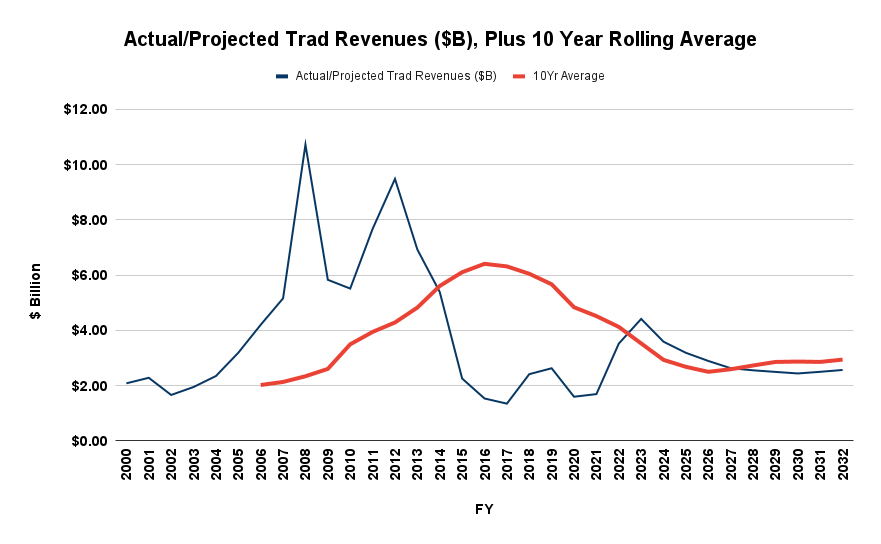

While between the two the best approach – in terms of the steadying the level of revenues – is to use the rolling 10-year average, even then the level of variation between years is significant. Looking at the following chart, it is clear that even using that approach, programs built up during the peak are likely to become challenged as time moves on and lower revenue years are included in the average.

At least, however, by using an averaging approach the variation between the peaks and valleys is narrower and the change from year to year smoother. And the potential exists going forward to make the flow over time even more smooth by adopting narrower sideboards limiting the rate of change from year to year.

4. Put all of the revenue options on the table and evaluate them objectively side-by-side. To us, one of the most important statements made during last year’s budget cycle came early on from the Legislative Finance Division (LegFin). At the outset of reviewing various “New Revenue” options in its “Overview of the Governor’s [FY23] Request,” LegFin stated that “equity, economic impacts, efficiency, and other considerations … should be addressed if the Legislature chooses to explore revenue options.”

Of course, as we pointed out in our column discussing the various budget gimmicks both the Administration and LegFin engaged in last year, LegFin didn’t follow through on its own advice, choosing to ignore throughout the “equity, economic impacts, efficiency, and other considerations” raised by using diversions from the PFD as the revenue option for balancing the budget.

But the fact that they ignored their own advice doesn’t make it bad advice. Indeed, it is one of the most important steps that any administration should be taking in constructing this year’s budget and 10-year plan.

One thing on which almost all – if not all – fiscal analysts agree is that different revenue options have different impacts on the various groups of Alaska families and the economy. Just like any administration should strive to find the right blend of spending measures that optimize the situation facing Alaska families and the overall Alaska economy, it should do the same on the revenue side as well.

To do that it should both evaluate and make transparent to Alaskans the “equity, economic impacts, efficiency, and other considerations” applicable to each option. Last year, the Dunleavy administration didn’t even come close to doing that, effectively sneaking in – without any discussion of the impacts – roughly $800 million in new annual revenues by restructuring the PFD from the current statutory approach to POMV 50/50.

The result is that, without any public evaluation or disclosure of the consequences, the administration proposed adopting the option that, of all the various revenue alternatives, has both the “largest adverse impact” on the overall Alaska economy and is, “by far,” the costliest option for 80% of Alaska families. By ignoring other, more equitable options, it proposed to shift a large portion of that $800 million out of the pockets of the “bottom 80%” of Alaska families indirectly into the pockets of the already well off top 20%.

The analysis suggested by LegFin isn’t difficult. Indeed, it’s as simple as filling in the following chart, most of the work on which has been done in previous studies.

So that Alaskans can understand the impact of the choices being proposed, any administration, regardless of who is governor, should engage transparently in such an assessment of the alternative revenue options as a regular part of presenting its proposed annual budget and 10-year plan.

Of course, we likely will have other comments and points to make once the new budget and 10-year plan are submitted in mid-December. But these four components are what we will look for first as a measure of whether the then-administration is being honest with Alaskans, treating future generations fairly, working better to stabilize the revenue stream on which the budgets are based and using revenue measures that are equitable to all Alaska families and have a low impact on the overall Alaska economy.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

A correction. A reader has noted on another page that the numbers in the “PFD Cuts (Diversions)” column in the chart under point “2” above don’t add to the “Total” stated for the column. The amount stated for the Total includes the amounts only through FY20. The correct number for the entire period thru FY23 (est) – and which should have been stated as the “Total” on the chart – is $6.675 billion. The remainder of the numbers on the chart are correct.