In our column a couple of weeks ago – “An updated 10-year outlook” – we proposed routinely including a line item for repayment of the Constitutional Budget Reserve (CBR) as part of any budget and 10-year plan.

That generated some pushback, with some arguing that since we only owe the amounts to “ourselves” it’s not really necessary to refill the reserve on any given schedule and certainly, shouldn’t restrict current spending or require new revenues to do so.

This column explains why we believe a repayment schedule is important, even if it impacts current spending or requires new revenues.

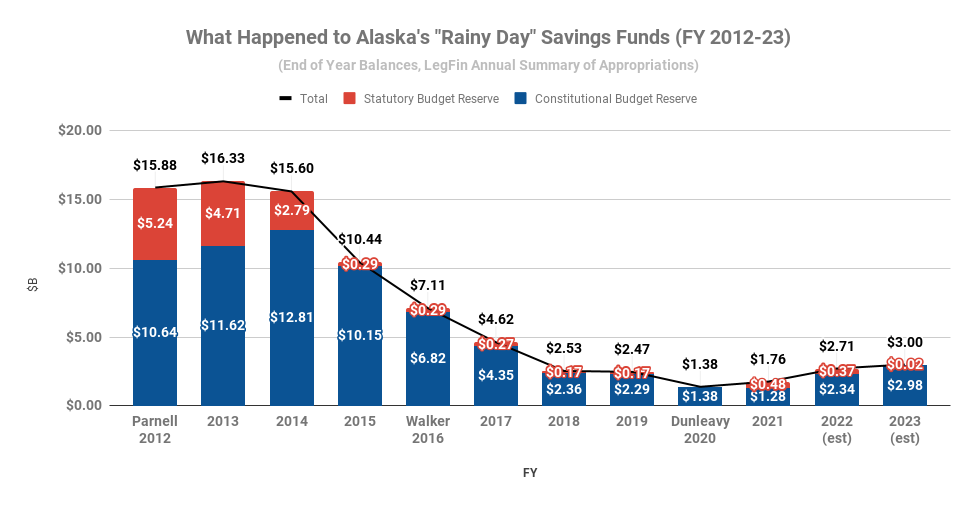

Here is what has happened to the CBR (in blue) – and the related Statutory Budget Reserve (in red) – since FY 2014, the last time the CBR was full.

Over the intervening period the balance in the fund has been drawn down from a high of $12.81 billion at the end of FY14 to a balance of $1.28 billion at the end of FY21.

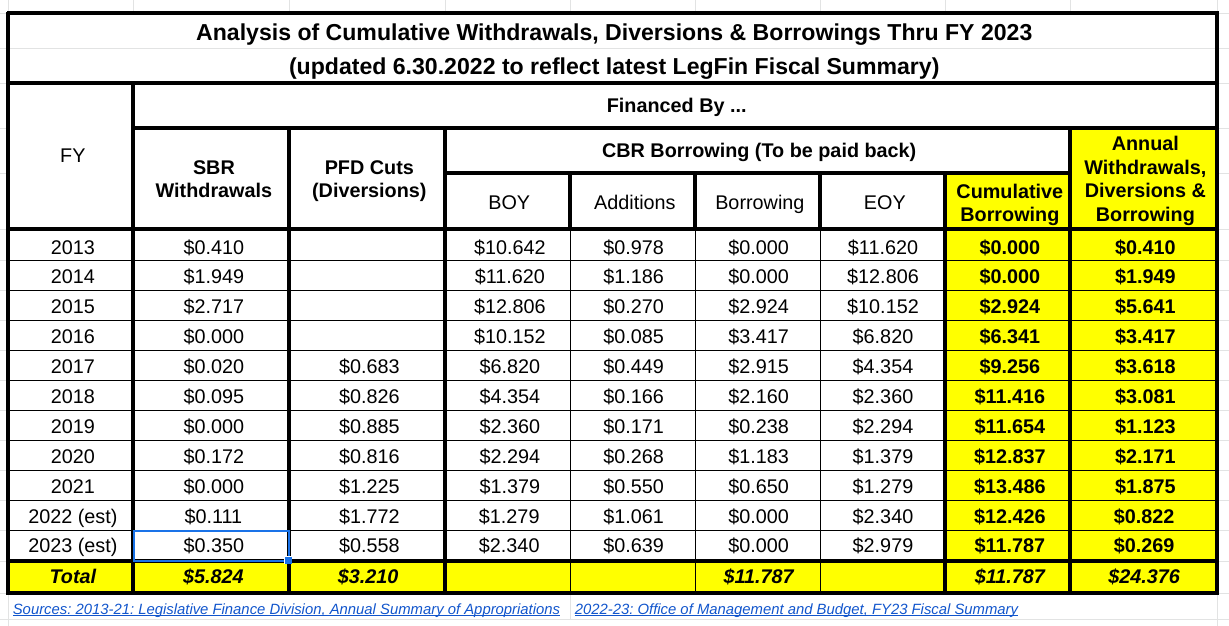

The amount owed to the fund as of the end of FY21 was actually greater than the $11.53 billion difference, however. Because, like any savings account – and as required by Art. 9, Sec. 17 of the Constitution – the fund actually generates a return on the amount retained during any given year, the total amount borrowed as of the end of FY21 was more in the range of $13.5 billion.

Due to higher projected revenues, both the Legislative Finance Division and the Administration’s Office of Management & Budget anticipate some repayments during FY22 and FY23, but not only are those repayments somewhat speculative, even then the total repayments ($1.7 billion) are less than the amount simultaneously being diverted from the Permanent Fund Dividend ($2.3 billion).

Essentially, the FY22 & FY23 budgets propose to repay at least some of the CBR through PFD cuts. As we discuss further below, we think that is a highly inappropriate policy.

The timing of CBR repayments. The most intense pushback we received on the position we outlined in the previous column was over the timing of any repayments. Most argued that since “we owe the payments to ourselves,” we should be able to repay them anytime “we” want. Many were adamant we shouldn’t make room in the budget for such paybacks if at the expense of current spending or if it requires raising additional revenue.

The CBR exists to serve as a backstop funding source in the event current spending exceeds current revenues. The reason it is required to be refilled is to ensure that any given generation isn’t able to drain it for its own benefit to make its life easier, then leave future generations on their own. The repayment obligation is to help ensure that each generation passes on the account to the next in at least as good a position as they found it.

To achieve that objective, each generation using the account to bridge over any fiscal gap it might encounter should refill it before the next generation arrives. It doesn’t serve the intended intergenerational goals if one generation is able to drain it, then pass it on to the next still drained, requiring the next to refill it up front before they are able to use it themselves to bridge over any fiscal challenges they may face.

The point at which one fiscal generation ends and the next begins is far from precise, but in Alaska’s case it falls within a fairly narrow band. Using Department of Labor estimates, over the past seven years – since the state started deficit spending – approximately 315,000 residents, or nearly 45,000 per year on average, have moved out of the state (“out migration”). On average, that’s about 6.1% of the state’s population per year over the same period. At the end of the seven year period roughly 40% of the state’s residents here when it started have departed.

Those leaving during the period are people who enjoyed the benefit of using the CBR to support deficit spending – receiving government services without having to pay for them – over all or at least some of the time they were here, but who won’t be around to help pay it back. Instead, at their departure their share of the burden is being shifted entirely to those who remain, plus those who move here only after repayments start.

To avoid that intergenerational inequity, we believe that each year the current generation should pay something toward any outstanding repayment balance. That won’t precisely match those who received the benefits of CBR draws with those who are making the repayments. Over any given period draws from the CBR may exceed repayments and some may leave the state before the draws from which they benefitted are fully balanced out.

But it will reduce the burden and avoid the current situation, where many are leaving the state without ever having made any contribution toward repayment of the draws from which they benefited, sticking those who remain and any subsequent newcomers with their entire share.

In our earlier column we calculated the annual repayment by amortizing the outstanding balance at the start of FY23 (approximately $12.4 billion) over a 15-year period. The result is an annual repayment amount of approximately $830 million. Given Alaska’s high turnover rate we easily could justify an amortization rate of 10 years (resulting in an annual repayment amount of roughly $1.24 billion), but even 20 years ($620 million) would help mitigate the virtually unlimited intergenerational inequity resulting from the current approach.

Frankly, we think creating an annual payback obligation also would impose some fiscal discipline in an area where Alaska currently has little. As we have seen during the last decade, draws from the CBR have been made by leaps and bounds. Over the seven-year period from FY15 to FY21, draws from the CBR alone (not counting additional draws from the SBR and diversions from the PFD) averaged nearly $2 billion/year. Believing that they could defer repayments until some distant point in the future, legislators essentially treated it as a cost-free pot of money from which they could continue to hand out government services despite not having sufficient current revenues to support them.

We believe constituents, and thus, legislators, would behave much differently if they knew draws would require repayment generally by the same generation receiving the benefit. Instead of using the funds to continue to kick the fiscal can down the road, we believe it would incentivize both constituents and legislators to face up to the state’s fiscal situation much closer to real time.

Who should make the CBR repayments. Earlier in this column we noted that, because PFD diversions exceed the amount being repaid to the CBR, PFD cuts implicitly are being used to cover at least part, if not all of the repayments.

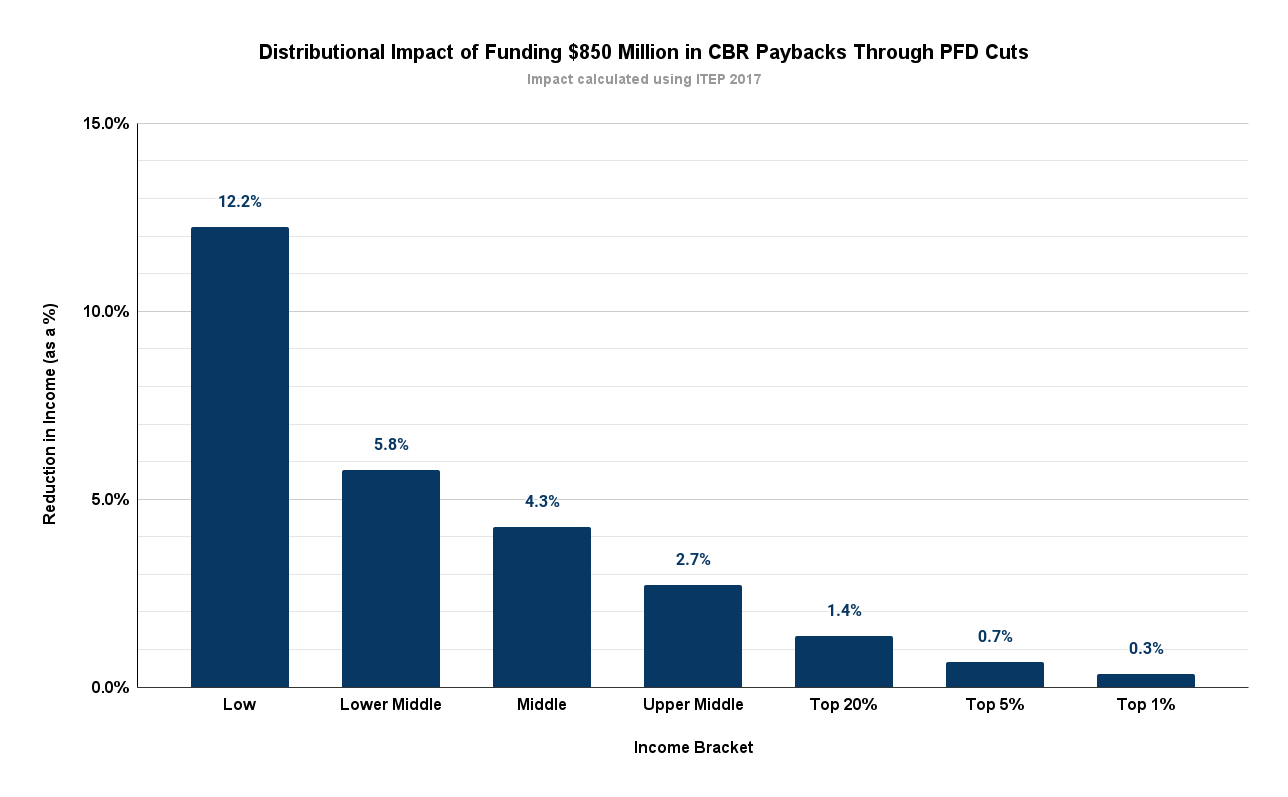

As regular readers of these columns will know, that means the burden for such repayments are being shifted largely to middle and lower income Alaska families. To borrow former Governor Jay Hammond’s words, those in the top 20% income bracket and non-residents are escaping nearly, if not entirely, “scot free” from any repayment obligation.

The Dunleavy administration’s Office of Management & Budget currently projects repayments of $1.061 billion and $639 million for FY22 and FY23, respectively, or an annual average of $850 million. Applying the methodology used in a 2017 report for the Legislature prepared by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (which we have discussed in detail in previous columns), by using PFD cuts as the source, this is how that repayment burden is being distributed.

As a share of income, low income Alaska families are contributing more than nine times more, middle income Alaska families more than three times more, and even upper middle income Alaska families more than two times more to the repayments than those in the top 20%.

As we have previously discussed, using PFD cuts to fund any category of government spending, including the repayment of prior CBR draws, has the “largest adverse impact” of all of the various revenue options on both 80% of Alaska families and the overall Alaska economy.

In addition, we are aware of no analysis that would show the prior CBR draws have been used to disproportionately benefit middle and lower income Alaska families, and even if so, certainly not to the same extent as using PFD cuts would adversely impact families in those brackets compared to those in the top 20%.

Instead, the CBR draws appear to have been used generally to support all Unrestricted General Fund (UGF) spending, which benefits all Alaska families.

As a result, we believe that, going forward, in years like FY22 and FY23, when oil and other traditional UGF revenues are insufficient to cover the CBR payback obligation, the necessary additional revenues should be raised from all Alaska families – and non-residents who also benefit from government services – in a manner which is both equitable and minimizes the impact on the overall economy.

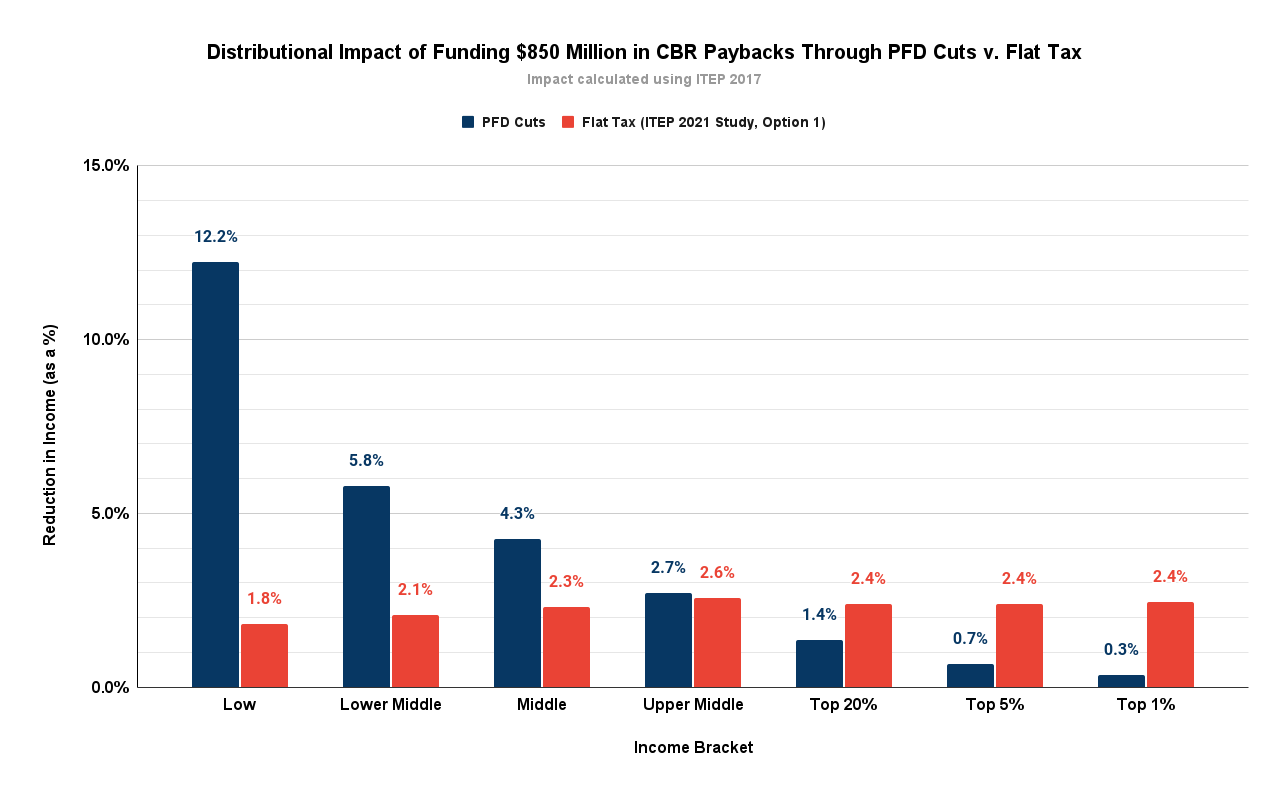

Here is the impact by income bracket (in red) if the necessary additional revenues for FY22 and FY23 had been raised, instead, through a flat tax.

Eighty percent of Alaska families would have contributed less than they did using PFD cuts. While the top 20% would have contributed more than they did using PFD cuts, they wouldn’t have contributed any more as a share of income than the remaining 80%, and still less than the remaining 80% did by using PFD cuts.

Bottom Line. The bottom line is that CBR repayments should be equitable both from inter- and intra-generational perspectives. No one generation should be able to avoid responsibility for any deficits they may generate in government spending by using CBR draws to kick the repayment obligation substantially, if not entirely, into the next generation. Any CBR draws should be repaid using an annual amortization approach that ensures at least some of the repayments are made by the same generation that directly benefited from the draws.

Similarly, no one income group should be able to avoid responsibility for any deficits from which they have benefited by using a repayment methodology that tilts the burden for the repayments largely to other brackets. All Alaska families benefit from CBR draws; all Alaska families should contribute toward repayments equitably.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Most Alaskans from 1985 to at least 2015 made no net payment to state or local government for any state or local service. If one wants to talk fiscal responsibility, we must first deal with the ignorant misconception that Alaskans are State stockholders and face the painful mess of facing actually paying for, well, anything.

Yeah. People learned about Alaska from “The Simpsons.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SdchHlmtn68