Over the course of the past week we have written extensively on our Facebook and Twitter pages and spoken at length on our weekly podcast segment about SB 199, the Senate Finance Committee’s proposed approach to a fiscal plan.

Under the version as forwarded out of Committee by a vote of 1 “Do Pass” (Senator Bert Stedman (R – Sitka)), 3 “No Recommendation” (Senators Click Bishop (R – Fairbanks), Lyman Hoffman (D – Bethel) and Natasha von Imhof (R – Anchorage)), 2 “Do Not Pass” (Senators David Wilson (R – Wasilla) and Bill Wielechowski (D – Anchorage)) and 1 “Amend” (Sen Donny Olson (D – Golovin)), the bill proposes to pay a Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) based on POMV 50/50 this coming fiscal year (FY23), but then reduce it to POMV 25/75 – a difference on average of about $1 billion per year ($1,500 per PFD) – in FY24 and subsequent fiscal years unless:

… by December 15, 2026, the commissioner of revenue and the director of the legislative finance division jointly agree that revenue measures anticipated to generate at least $800,000,000 of new annually recurring general fund revenue, when compared to annual revenue generated from the statutes as they read on June 30, 2022, have been passed by the Alaska State Legislature and enacted into law.

A POMV 50/50 PFD would be restored “only if” the commissioner and director “notify the revisor of statutes in a joint letter” by the prescribed date that the threshold has been met. Otherwise under the revised statute, the PFD would remain at POMV 25/75 in perpetuity.

Among the many problems we have outlined with SB 199 is that the $800 million in new revenue required to maintain POMV 50/50 is both far too steep and badly mistimed.

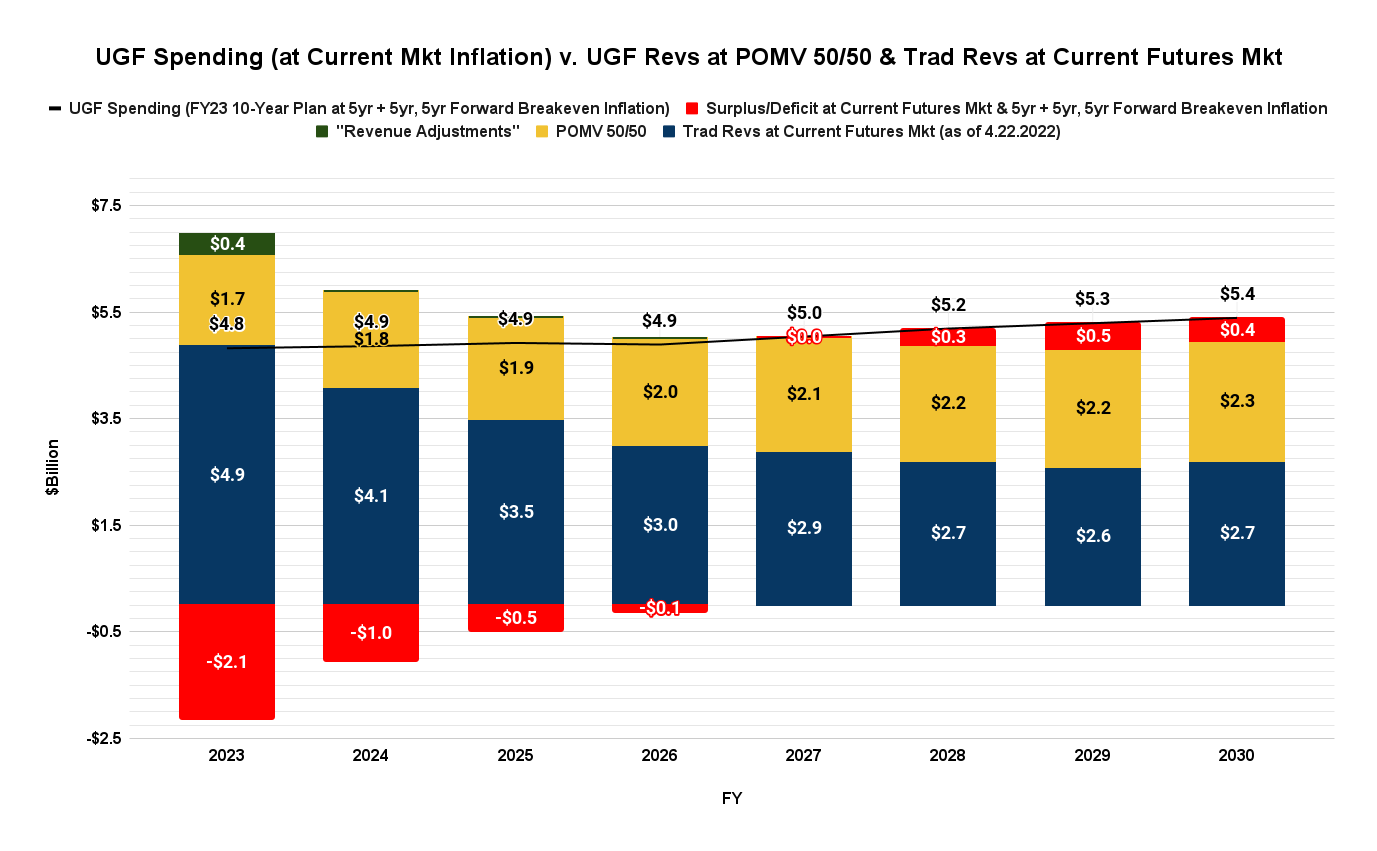

To explain, using the most recent versions of the “Goldilocks” charts we discussed in a previous column, we have charted the impact of using POMV 50/50 PFD through the remainder of the decade based on current oil futures prices and projected spending levels, adjusted for current market estimates of inflation rates.

As the analysis demonstrates, based on current market projections using POMV 50/50 the budget remains in surplus (red below the line) from FY23 through FY26 and even by FY30 is still only $400 million in deficit (red above the line). Offsetting the deficits against the surpluses results in a net surplus of $2.5 billion over the period from FY23 to FY30.

Under those circumstances, requiring any sort of new revenue to maintain POMV 50/50 before FY27, and even by FY30 requiring new revenue of greater than $400 – $500 million per year, is clearly excessive.

Put another way, over FY23 – 30 the SB199 approach would shift significantly more – on the order of $5 billion more – from Alaska’s private sector to government than is necessary to pay for government services.

That is bad both for Alaska families, who would be tasked to pay for most if not all of the excess, and, through them, the overall Alaska economy.

But as much as we believe SB199 is a very bad bill, we agree there is a need in the near future to put in place some sort of supplemental revenue approach as a contingency.

As the analysis above itself shows, on its current course there is a persistent budget deficit developing by the end of the period. And if the past decade has (re)taught us anything, despite projections based on legitimate futures market prices, expecting oil prices to remain at a given level over a prolonged period injects a material level of risk into the budget process.

Putting a contingent revenue plan in place to deal with those makes a lot of sense.

For ideas, we turned recently again to former Governor Jay Hammond’s seminal essay on Alaska fiscal policy, Diapering the Devil.

The reason we did is because Hammond contemplated similar issues both in the 1980’s and then again, early 2000’s. One thing we have learned about Alaska fiscal policy over the years is that nothing’s really new, it’s just the same issues popping up in different guises over and over again.

After the surge in new oil revenues following the commencement of deliveries from the TransAlaska Pipeline System (TAPS), in the early 1980’s then-Governor Hammond faced a significant push from the legislature to repeal the state’s then-existing income tax. Hammond resisted, arguing that while oil revenues might be flush then, that might not always be the case and, as a result, the state should have a backup revenue plan in place.

As Hammond explains in the essay, at the time he asserted that abolishing the income tax “was the most stupid thing we could do. Reduce or suspend it but don’t take it off the books completely.” Rather, he argued, by suspending the tax, it would hang “like a Damoclean sword over the legislature, threatening to decapitate them if they permitted spending to spin out of control.”

In short, having a contingency plan in place would serve both as a backup revenue source in the event the need arose, as well as an implicit spending cap.

As history tells us, of course, the legislature ignored him and went ahead with repeal, leaving the state short-handed when, as Hammond feared, oil prices subsequently plunged in the mid-1980’s.

In the book, Hammond recounts pushing a similar approach also a second time. In 2002, he and former Senate President Rick Halford developed a backup, “insurance” approach that ultimately came to be called the “Parachute Plan.” That plan:

… required a threshold be set beneath which the CBR [Constitutional Budget Reserve] could not be depleted without triggering means to recoup revenues required to bring it back up to that threshold. This could be accomplished through either budget cuts or increased taxes. If the latter, they would only be imposed to the extent necessary to retain the CBR threshold and then would be suspended or declined accordingly if no longer needed.

Reflecting on those, we think the time and opportunity may be right again to develop – and finally implement – a similar, trigger-based revenue contingency plan.

Because the POMV 50/50 approach likely remains in surplus for the next several years, the contingency source would not be used immediately, but rather as with Hammond’s approach, would hang like a sword of Damocles over the legislature if it subsequently once again permitted spending to outstrip revenues.

In our view, using the status of the CBR – as Hammond suggested in the “Parachute Plan” – continues to be a useful trigger.

While the numbers remain in flux, on its current path the CBR – or the CBR and SBR [Statutory Budget Reserve] combined should the legislature decide to route some of the surplus to the SBR instead – should end the current fiscal year (FY22) somewhere above $2 billion and then grow larger in FY23, creating an initial cushion for implementation of the Plan.

A modern-day “Parachute Plan” would build off that, triggering new revenues or spending cuts – or a combination of both – if and when the reserves subsequently fell below that threshold in the future.

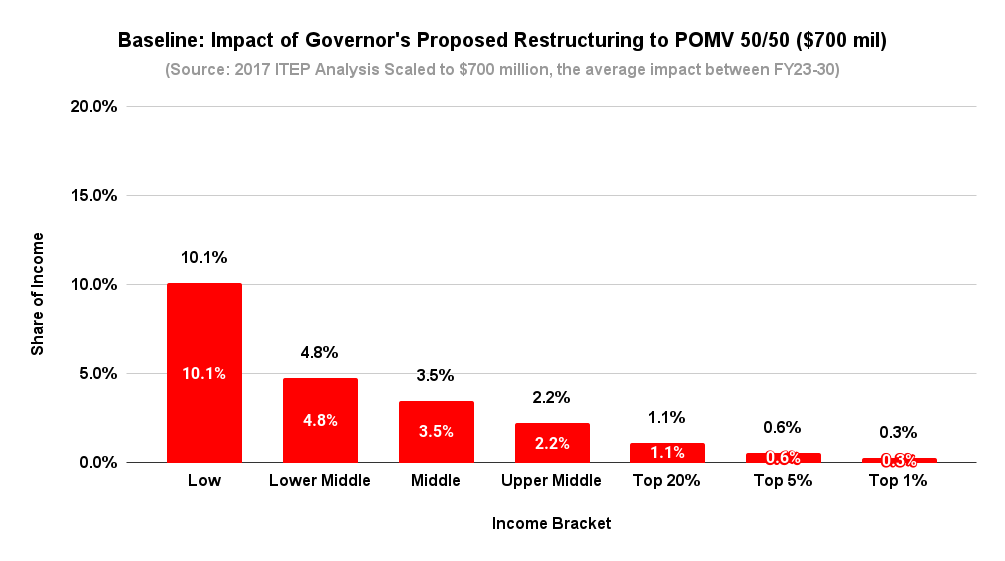

We have seen what happens when the CBR is drained without a plan in place for dealing with it. The Legislature has resorted to PFD cuts – the revenue approach that has the “largest adverse impact” on 80% of Alaska families and the overall Alaska economy – as a default.

As a result, to be effective the Parachute Plan would need to specify what happens when the threshold is breached, for example a combined spending cut and new revenue implementation that would share equally (50/50) in offsetting the shortfall. Both would need to be spelled out. The portion from spending cuts could be taken across the board, for example, with the revenue portion derived through a flat tax (or other equitable, low impact mechanism) already specified by statute.

While some might argue that additional PFD cuts should also be included in the Plan, they shouldn’t. Recall that middle and lower income Alaska families already will have borne a disproportionate share of the burden in the first step of the fiscal approach, reducing the PFD from the current, statutory level to POMV 50/50. As we have previously discussed, using PFD cuts take much more as a share of income from middle and lower income Alaska families than the Top20%:

As a result, any further revenues required subsequently to be deployed under the Parachute Plan should draw equitably from all Alaska families, not double down again disproportionately on middle and lower income families.

Moreover, requiring all Alaska families to be exposed to the risk of contributing additional revenues is a key piece of the Plan’s deterrence role. As Governor Hammond said, “[a]fter all, the best therapy for containing malignant government growth is a diet forcing politicians to spend no more than that for which they are willing to tax.”

In order for that, in fact, to act as a deterrent, all Alaska families, including those in the Top20% donor class so important to legislators’ careers, need to be exposed to the potential for such taxation as well.

The bottom line is this. While the outlook for the state’s finances under POMV 50/50 justify the creation of some sort of fiscal contingency plan, they come nowhere near to justifying the huge financial overreach embodied in SB199, which would transfer more than $5 billion in excess revenues out of the pockets of Alaska families and the Alaska private sector to government over the remainder of this decade.

A much, much better approach is to look to Governor Hammond’s proposed Parachute Plan, which creates a contingency mechanism which both carefully backstops state finances in the event of additional needs and creates a deterrent to excess spending which would hasten that day.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.