Over the past three years, we have used columns during the summer and fall to fill gaps in the Department of Revenue’s (DOR) regular cycle of state revenue forecasts. As we said when we began the practice:

The Department of Revenue publishes two formal revenue updates each fiscal year. The first is the detailed Fall Revenue Sources Book, published in December in connection with the submission of the governor’s budget. The second is the Spring Revenue Forecast, published three months later, in March, as the Legislature comes to grips with the annual budget.

While the Department also publishes occasional updates, those have a more limited circulation and aren’t as widely used as a public source of data for changes in the state’s fiscal outlook.

So, as part of our Alaska Landmine “Chart of the Week” series, we are going to attempt to help fill in the 9-month gap between the Fall and Spring forecasts with two additional three-month looks in mid-June and mid-September.

Last year, we modified that schedule to publish only one interim look — in late August, midway between the state’s official looks in March and December. We are continuing that practice this year.

As in previous updates, we review the outlook separately for revenues, spending, and the net.

Revenues. There are two significant drivers of state revenues under current law: oil revenues (which, in turn, are a combination of prices and production levels) and the portion of Permanent Fund earnings that are available for state government under current law (i.e., the percent of market value (POMV) draw remaining after deducting current law Permanent Fund Dividends (PFD)).

At present, the near-term (next two-year) outlook for oil revenues is highly uncertain due to significant uncertainty about future oil prices. Currently, the futures markets, which are used as the basis for DOR’s semi-annual revenue forecasts and for our weekly looks at projected revenues, are saying one thing, while the federal Energy Information Administration (EIA), which monthly publishes a forward-looking Short Term Energy Outlook (STEO) that includes a detailed oil price projection, is saying something significantly different. We explained what is driving the EIA’s view in an earlier column.

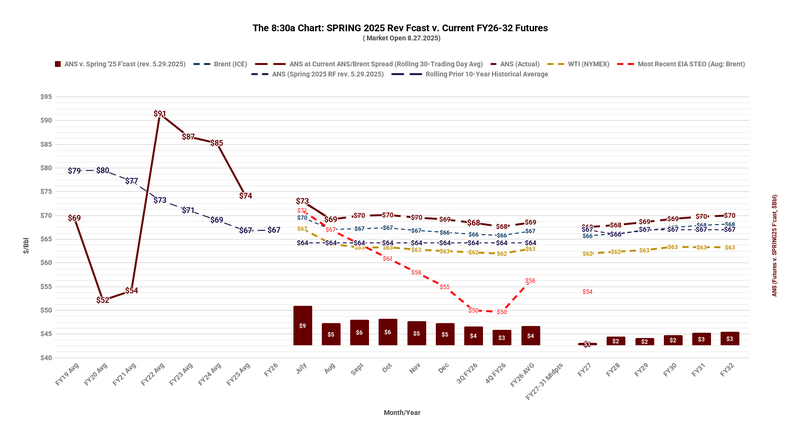

We include both sources in our daily “8:30am Chart,” which follows past, current, and projected oil prices for a period extending six years beyond the end of the current Fiscal Year (FY). Here is the most recent chart as we are writing this week’s column:

Looking at the middle of the chart, which covers the current fiscal year (FY 2026), the current futures market oil prices for Brent, adjusted for the current differential between Brent and Alaska North Slope (ANS), are reflected by the long-dashed maroon line at the top. Using that approach, the current projected average price for ANS is $69/barrel.

On the other hand, the current oil price for Brent projected for the same period by the EIA in the most recent STEO (the August EIA STEO), which is reflected by the dashed red line, declines significantly over the year. Using that source, the current projected average price for ANS, adjusted by the same differential between Brent and ANS as used for the futures market price, is $58/barrel.

The significant differences continue into FY 2027. There, the projected price using the futures market is $68/barrel. The projected price, based on the August 2025 EIA STEO, is $56/barrel.

As we explained in a previous column, the differences between the two price levels cause a significant disparity in projected revenue levels for FYs 26 and 27, the years covered by the August EIA STEO.

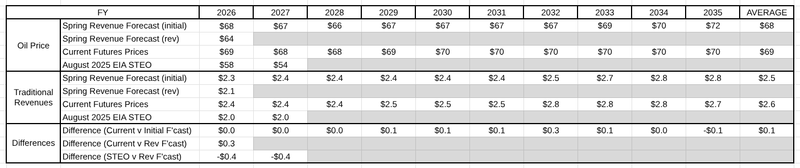

In the following chart, we include projected prices and traditional revenues included in (1) the Spring 2025 Revenue Forecast as originally published in March (the initial Spring Revenue Forecast), (2) the revision to that forecast for FY 26 later published by DOR on June 12, 2025 (DOR’s June 12 Revision), (3) calculated using the current oil futures market, and, (4) for FY 26 and 27 (the only years covered), calculated using the August EIA STEO.

As is clear, there are significant differences between the price levels projected for FYs 26 and 27 in the initial Spring Revenue Forecast and the current futures market on the one hand, and the price levels projected for FY26 in DOR’s June 12 Revision and for FYs 26 and 27 in the August EIA STEO on the other.

As the bottom section of the chart (“Differences”) demonstrates, the differences in projected prices also result in significant differences for FYs 26 and 27 in the projected level of traditional revenues.

For FY 26, DOR’s June 12 Revision results in a $300 million reduction in traditional revenues from the initial Spring Revenue Forecast and current futures market price levels, and the August EIA STEO results in an additional drop of $100 million beyond that. For FY27, the August EIA STEO results in a $400 million reduction in traditional revenues from the initial Spring Revenue Forecast and current futures market price levels.

After FY 27, both projected oil prices and traditional revenues over the period derived from current futures market prices remain within 5% of the projections made in the Spring Revenue Forecast, a non-significant difference.

Separately, while current FY 26 production levels are running materially below forecast, it is still early in the year. The production levels required over the remainder of the year to make up for the early deficiencies are well within a realistic range. Therefore, we have not adjusted the revenue forecast in this update for changes in production levels.

In the “Net” section at the end of this column, we will include separate lines reflecting revenues for FYs 26 and 27 at the oil price levels reflected in the initial Spring Revenue Forecast (which are the same as those reflected in the current futures markets), and those in the August EIA STEO.

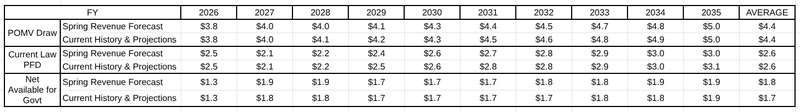

Different from traditional revenues, the projected level of Permanent Fund earnings available for state government has remained relatively stable since the Spring Revenue Forecast. We update our projections of those levels monthly using the most recent “History and Projections” report from the Permanent Fund Corporation.

Here are the most recent projections as we write this week’s column, compared to those that were included in the Spring Revenue Forecast:

While the projected level of the POMV draw is slightly higher in some years over the forecast period than that included in the Spring Revenue Forecast, so is the projected level of PFDs under current law. The net effect is that the portion of the Permanent Fund earnings available for government under current law remains largely unchanged.

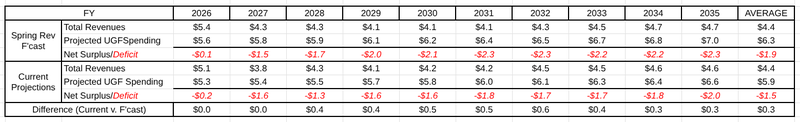

Combining the two (and substituting the appropriated PFD level for the current law level for FY26), here is the resulting total level of revenues projected over the period in the initial Spring Revenue Forecast compared to current projections using the August EIA STEO:

As is clear, the significant differences between the initial Spring Revenue Forecast and the current projections are those driven by the use of the oil prices included in the August EIA STEO for FY 26 and 27. For those years, total revenues are 6.7% and 10.2% lower, respectively, than those reflected in the initial Spring Revenue Forecast. For both years, current projected revenues are running approximately $400 million below those projected in the initial Spring Revenue Forecast.

While there are some slight differences from year to year for the remainder of the period, those largely wash out when averaged over the period. Outside of FYs 26 and 27, projected average annual total revenues are within 1% of those projected at the time of the Spring Revenue Forecast. Apart from FYs 26 and 27, total projected annual revenues over the period range from $4.1 billion at the low end (FY 29) to $4.6 billion at the high end (FY 28), averaging $4.4 billion per year for the period as a whole.

In some previous budget updates, we have also included estimates of future revenues based on a 10-year rolling historical average of oil prices. As we explained in an earlier column, using the 10-year average is a much more robust fiscal approach than relying on future oil price projections, as the state currently does. To align these updates with the budget cycle, rather than adding them to this outlook, we will update the rolling 10-year analysis going forward when the Department of Revenue publishes its Spring and Fall Revenue Forecasts.

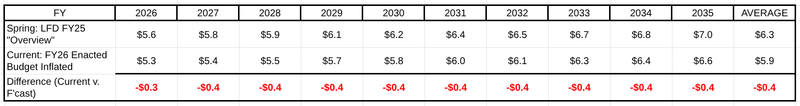

Spending. While projected spending levels are not included in the Department of Revenue’s Fall or Spring Revenue Forecasts, we include them in these updates to provide a complete overview of projected future budgets and deficits. In this update, we use the Legislative Finance Division’s (LegFin) estimates of unrestricted general fund spending levels included in its pre-session “Overview of the Governor’s [FY26 Budget] Request” (Overview) to represent projected spending levels current as of the time of the Spring Revenue Forecast.

To represent currently projected spending levels, we use the FY 26 unrestricted general fund spending levels included in the enacted budget as reflected in LegFin’s July 10, 2025, FY 2026 “Budget Summary,” including the so-called “surplus” reserved for supplemental FY 26 spending, escalated annually over the remaining period at the projected rate of inflation included in the Permanent Fund Corporation’s most recent “History and Projections” Report (2.5%).

Here are the results:

The chart indicates that the enacted FY 26 budget is materially (5.4%) lower than the level projected in LFD’s pre-session overview. Because both starting levels are escalated at roughly the same rate, that relationship stays relatively constant.

In addition to spending on current needs, we believe that, as part of the annual budgeting process, the Legislature and Governor also should include an additional amount to pay back the outstanding balance of the Constitutional Budget Reserve (CBR) over a defined period, similar to payments made to amortize debt owed to third parties. As we explained in a previous column, the near-term payback of that balance is appropriate to ensure that the same generation that benefited from borrowing from the CBR pays back the amounts. We last analyzed that issue in detail in 2022, three years ago. We will update those numbers in an upcoming column.

Net. Between diverting a significant portion of the current law PFD to unrestricted general fund revenue and reducing spending, the Legislature thought when it left Juneau earlier this year that it had both created breathing room for the FY 26 budget and, assuming continued deep PFD cuts, had positioned itself well also for the FY 27 budget. Adding the PFD cuts made to the traditional revenues included in the Spring Revenue Forecast resulted in overall revenues ($5.4 billion) being slightly in excess of projected overall spending ($5.3 billion, down from the $5.6 billion in spending projected in LegFin’s earlier Overview).

That might remain the outcome if oil prices stay on track with the current outlook in the oil futures market, which continues to follow those included in the initial Spring Revenue Forecast closely.

On the other hand, if, as the year unfolds, actual oil prices ultimately more closely reflect either DOR’s June 12 Revision, or, worse from a budgeting standpoint, those projected in the August EIA STEO, the FY 26 budget will end in yet another deficit. While the deficit won’t be any greater than that initially projected using LegFin’s Overview and the initial Spring Revenue Forecast, the state still will be facing a hole of roughly $200 million instead of the “balanced” budget the Legislature thought it had adopted when it left Juneau at the end of the regular session.

Beyond FY 26, the outlook remains largely unchanged from previous projections, with significant current-law deficits persisting throughout the entire period. While, if maintained over the period, the steps taken by the Legislature earlier this year to reduce current spending will also serve to reduce the level of future current law deficits, substantial deficits nevertheless remain, ranging from $1.6 billion for FY 27 to $2.0 billion by FY 35.

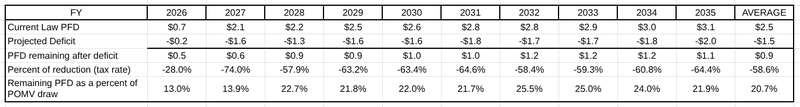

Here is the impact on PFDs, assuming the deficits continue to be covered entirely through PFD cuts over the period (the so-called “leftover PFD” approach). As noted above, we calculate and update projected current law PFDs monthly using the Permanent Fund Corporation’s most recent “History and Projections” Report:

Aside from FY 26 (which, by using the appropriated PFD, already reflects the cut from the current law PFD), the level of PFD cuts increases over the period, ranging from a low of $1.3 billion (FY 28) to a high of $2.0 billion (FY 35). Because projected current law PFD levels rise at a faster rate than the deficits, however, the percent reduction in the current law PFD – or, using Professor Matthew Berman’s phrase, the “tax rate” on the PFD – actually falls from 74% to roughly 64%, and the percent of the projected POMV draw distributed as PFDs rises slightly from approximately 14% in FY 27 to approximately 21% in FY 35.

As we have explained in previous columns, using PFD cuts to balance the budget is highly regressive – it takes an increasingly larger share of income from middle- and lower-income Alaska families than from those in the upper-income brackets. Indeed, Professor Berman concludes that the approach is “the most regressive tax ever proposed.”

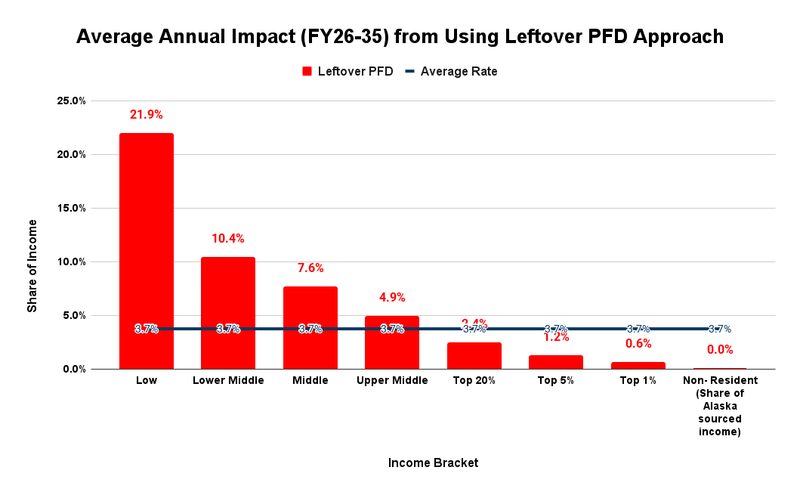

Here is the projected average annual impact of those cuts by income bracket over the period if the deficits continue to be covered entirely through PFD cuts:

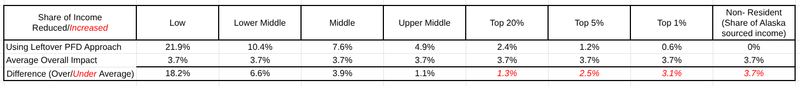

At an annual average of $1.5 billion, closing the deficit through PFD cuts reduces projected adjusted Alaska gross income over the period by approximately 3.7%. But the impact is hugely uneven across income brackets. The following chart compares the difference over the period by income bracket:

As a result of using PFD cuts to balance the budget, the average income of Alaska households in the lowest 20% income bracket is reduced by more than 18% more than the average Alaskan household, the income of those in the lower middle-income bracket is reduced by more than 6% more than the average, the income of those in the middle-income bracket is reduced by nearly 4% more, and the income of even those in the upper middle-income bracket is reduced by more than 1% more.

On the other hand, by using PFD cuts to close the deficits, Alaska households in the top 20% realize savings (essentially, a tax cut paid for by overcollections from those in the middle and lower-income brackets) of over 1% in income over the average impact, those in the top 5% savings of over 2% over the average impact, those in the top 1% savings of more than 3% over the average impact, and non-residents, who contribute nothing, retain 3.7% more income than if they were subject to the same average tax rate on their Alaska sourced income as everyone else.

Put another way, by using PFD cuts to close the deficit, those in the lowest 20% income bracket will see their income reduced by nine times more than those in the top 20%, those in the lower middle-income bracket will see their income reduced by more than four times than those in the top 20%, those in the middle-income bracket will see their income reduced by more than three times than those in the top 20%, and those in the upper middle-income bracket will see their income reduced by two times more than those in the top 20%.

On the other hand, those in the top 5% will see their income reduced by only half as much as those in the top 20% overall, and those in the top 1% will see their income reduced by only a quarter of those in the top 20% overall. Non-residents who contribute nothing will retain all their Alaska-sourced income, while those in the top 20% will see theirs reduced by 2.4%.

In sum. By reducing spending from the initial levels projected by LegFin, the Legislature reduced the deficit—and preserved more of the PFD—compared to the levels initially anticipated at the time of the Spring Revenue Forecast. If revenues hold at the levels projected in the initial Spring Revenue Forecast, the state will avoid a deficit. If, on the other hand, oil prices fall as projected in the August EIA STEO, FY 26 will end up in deficit even after the spending reductions, and FY 27 will become even more challenging than previously thought.

Beyond FY 27, the state continues to face staggering current law deficits. While the currently projected levels are smaller than the previous ones, that assumes that overall spending growth going forward is limited to no more than the rate of inflation. If actual spending growth increases at higher levels, projected deficits will also grow.

By using PFD cuts to close the resulting gap, middle and lower-income Alaska households – which combined, are 80% of Alaska families – are growing poorer than all Alaskan households on average, while those in the top 20% and non-residents are growing richer than the average at rates far greater than those resulting from the fiscal approaches used in other states. If not driving, the disparity certainly contributes to the outmigration of working-age Alaska families. The numbers are in plain sight. Those who ignore the impacts are simply disregarding a continually deteriorating situation.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Brad always does a great job connecting the dots between oil prices, spending, and real impacts on households.

The article makes a strong point about the regressiveness of hole io relying on PFD cuts. Are there any realistic alternatives being discussed in Juneau?

Even small shifts in oil prices can mean hundreds of millions in budget impact.

slope