In a recent op-ed that is making its way through the state’s newspapers and other media outlets, former Revenue Commissioner Bruce Tangeman rhetorically asks, “Does Alaska have a revenue problem or a spending problem?

It takes a while for him to get there, but he finally seems to settle on the revenue side:

Taxes will soon be required to balance our budgets going forward, but it will mean a seismic shift for the Alaskan economy. My deep concern is with the impact on the economy by attempting to extract enough revenue from the working Alaskans through an income and/or sales tax to satisfy our constitutionally required balanced budget.

Tangeman’s “deep concern,” however, is nearly a decade overdue. As early as 2016, researchers at the University of Alaska – Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) warned that of all the tools available to the state, including income and sales taxes, raising revenue through cuts to the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) would have “the largest adverse impact on the economy per dollar of revenue raised.” Some of those same researchers later concluded in 2017 that of all the those same tools, a “cut in PFDs would be by far the costliest measure for Alaska families.”

Yet, that was the option – and the only option – chosen by then-Governor Bill Walker in 2016. Since then, every subsequent Legislature has followed the same approach annually, and every succeeding governor has approved it.

The reasons behind the researchers’ conclusions – that the cuts are significantly regressive and solely impact Alaska families (rather than also raising revenue from non-residents, which would considerably lessen the burden on Alaska families) – remain unchanged.

In fact, just two years ago, one of the original researchers – long-time ISER professor Matthew Berman – reiterated the findings:

Let’s be honest. A cut in the PFD is a tax — the most regressive tax ever proposed. A $1,000 cut will push thousands of Alaska families below the poverty line. It will increase homelessness and food insecurity.

In his op-ed, Tangeman avoids addressing that issue, blithely dismissing the discussion of PFD cuts as a “distraction.”

But it isn’t. Regardless of whether or not labeling PFD cuts as “taxes” is rhetorically justified (Berman clearly believes it is, while Tangeman does not), there is no doubt that they reduce income for working Alaskan families in a massively regressive manner, disproportionately affecting middle and lower-income Alaska families – and through them, the Alaska economy – most severely of all of the options.

If Tangeman is genuinely concerned about the impact of raising revenues on the economy and working Alaskans, that concern would have been evident long ago, including during his brief (less than 15-month) tenure as Alaska’s Revenue Commissioner, when he could have recommended action.

Instead, he is only voicing that concern now, as the PFD nears exhaustion and revenues will likely also need to be raised from upper-income Alaskan families, non-residents (and, through them, the industries that employ them), and oil companies. Tangeman’s newfound concern seems to focus on the upcoming impact on those interests rather than the middle and lower-income working Alaska families who have continually been adversely impacted since 2016.

But even once he finally gets to the answer, Tangeman is wrong. Alaska’s problem isn’t either “too much” spending or “too little” revenue. Instead, it’s been the failure to utilize an efficient revenue design that broadly spreads the burden of additional government spending so that all Alaskans have a material stake in the spending levels and, thus, an incentive to establish a balance between spending and revenues.

As Tangeman notes, Alaska’s fiscal mindset has historically been based on the perception that state revenue is a “free” good. That perception has resulted in Alaska developing few constraints around spending. After all, when the revenue to pay for it is “free,” why bother?

The facts underlying that perception changed abruptly for some in 2016, when first former Governor Walker, and then in the subsequent year, the Legislature, started to withhold and divert income due to Alaskans under current law to pay for government. The consequence was that some Alaskans began to realize that additional government spending was no longer “free” and started to push back on spending levels. But because they felt the impact hardest, those largely tended to be middle and lower-income Alaska families.

Upper-income Alaska families, on whom PFD cuts have a trivial impact as a share of income, as well as non-resident employers and the oil companies, who were unaffected by the PFD cut, did not. Instead, from their perspective, they viewed the PFD cuts as a type of tax credit, resulting in the continuation of “free” government services to them, even as others paid for those services through reduced income.

As a result, even since 2016, when the imbalance between revenues and spending became obvious, those to whom PFD cuts mean little have continued supporting growth in government spending. As before, when the revenue to pay for it continues to be “free” to them, why bother opposing it?

The result would have been different if, instead of using regressive PFD cuts, the revenue had been raised broadly through a revenue design that required contributions not only from middle and lower-income Alaska families but also those in the upper-income brackets, as well as non-resident industries and others with significant political power. As former Governor Jay Hammond once said, “After all, the best therapy for containing malignant government growth is a diet forcing politicians to spend no more than that for which they are willing to tax.”

A flat rate (or what some call a proportional) tax design spreads the burden broadly, taking the same from all to whom it applies rather than, as do either progressive or regressive taxes, more from some than others. Ultra broad-based sales taxes can be designed largely to have the same effect.

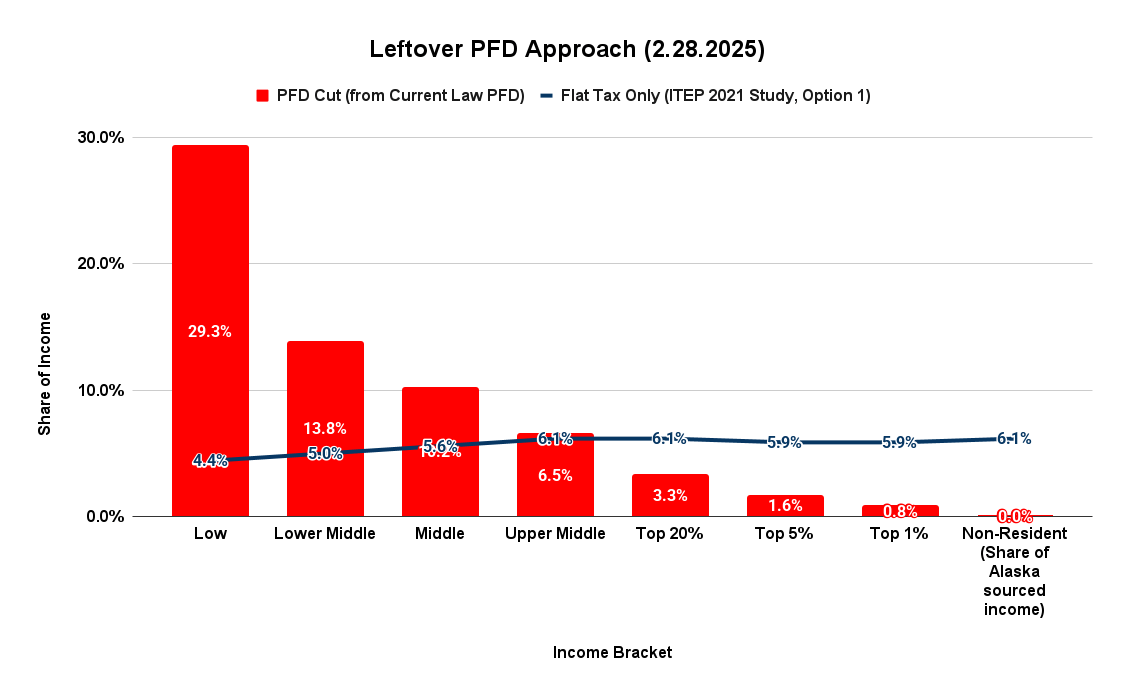

The difference between the two is reflected in this chart.

Both approaches raise the same amount of revenue. The impact of raising revenues using PFD cuts by income bracket is in red. Based on a 2021 study for the Legislature by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), the effect of using a flat tax is reflected by the blue line. The differences are clear. Using PFD cuts concentrates the impact on the middle and lower-income brackets, while those in the upper income brackets contribute much less and non-residents nothing. Using a flat tax or other broad based approach on the other hand impacts all brackets, including non-residents, roughly the same.

As the Tax Foundation explains, the shared impacts from a flat tax and other broad-based approaches have an effect: “Of greater significance for taxpayers, however, is that flat-rate income taxes tend to function as a bulwark against unnecessary tax increases.” Because everyone has the same stake, “they also tend to be harder to raise in the future.” Legislators cannot use the divide and conquer tactics as they can with graduated (progressive or regressive) taxes. Everyone has the same skin in the game.

Such a revenue design also helps balance constituents’ desires for government spending with their willingness to pay for it. They do not prevent additional spending. Legislatures can still increase spending. However, since everyone pays a proportionate share of the increase, doing so requires reaching a general consensus that the additional spending is needed. That eliminates the current situation in which some people, for whom the government is a “free good,” push unrestrainedly for additional spending, knowing they won’t feel the consequences themselves.

Had the Alaska legislatures since 2017, or Tangeman while he was Revenue commissioner, implemented such an approach, there wouldn’t be either a spending or revenue problem today. Increased spending would have occurred only when a general consensus existed that it justified increasing revenues.

Some argue that implementing such an approach only exacerbates a “spending problem” by giving legislators more money. But it doesn’t. Because everyone is required to pay a share, legislators will be able to raise more money only when there is a general consensus that the additional spending is justified. That won’t reflect a “spending problem;” instead, it will reflect a general consensus that the additional spending is needed.

And it certainly creates less of a “spending problem” than PFD cuts have, with successive legislatures growing spending more and more by diverting more and more of the amounts statutorily designated as PFDs to fund government instead.

In short, as economists routinely advise, it’s all about incentives. As long as those in control believe that “free” revenue is available, they will be incentivized to spend it or at least not oppose others’ spending it. That’s what we’ve experienced over the last several years with the use of PFD cuts.

However, once the incentives shift to require everyone to contribute a material share of the costs, additional spending will proceed only when there is a general consensus that it is worth the additional revenue.

The failure to adopt that approach in place of PFD cuts is the root of Alaska’s fiscal “problem.” It’s not excessive spending or insufficient revenue; it’s the failure thus far to implement an approach that requires all Alaskans to balance both aspects.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Withholding $1500 from everyone’s PFD payout is financially identical to taxing those same people $1500. Identical, in fact, to a head tax, which is an unbelievably regressive tax because even children pay it.

“SB21” is not mentioned in this post but this:

“…in 2016, when first former Governor Walker, and then in the subsequent year, the Legislature, started to withhold and divert income due to Alaskans under current law to pay for government.”

is 100% the result of SB21.

Government spending at unsustainable leveles is the cause for Bill Walker and subsequent legislatures taking PFD’s away from every Alaskan, 100%. They had other options that they chose not to take.

Not. Spending had not changed from one year to the next, but revenue dropped like a lead brick.

Spending more than tripled prior to SB-21, it dropped a little after but has remained artificially high thanks to the taking of the PFD and spending (there’s that word again) of the Constitutional Budget Reserve and other savings. It’s 100% a spending issue. If SB-21 hadn’t been enacted by the legislature and retained by voters there would be less money to spend today than if aces were still in place and spending would still be the problem.

Look at the numbers for 2016

636,000 checks issued $(2052 – 1022) = $1030 “missing” from each check

equals

$655 Million diverted from PFD payout

Please check for yourselves whether the SoA budget was 655 million dollars higher in 2016 than it was in 2015.

John,

You need to review a couple more years of state budget, go back at least to aces if you want a return to aces, but going back a few years before that helos as well. Don’t cherry pick data, use the data to inform yourself.

No taxation with a Universal Basic Income welfare system.