One Man’s Mountain

How decades of dysfunction on the Anchorage Hillside allowed one man to gate the Stewart Trail and seize control of upper Potter Valley

An Alaska Landmine Special Feature by Paxson Woelber

With additional reporting by Jeff Landfield

December 2, 2019

The mountain goes unnamed on current maps and hikers simply refer to it as “East McHugh,” but 1979 USGS maps briefly gave it its own name: Ruby. Anyone familiar with the peak would find that name fitting. Rising above the Potter Valley neighborhood on the southeast corner of Chugach State Park, its summit and the ridges below it have a graceful symmetry uncommon in the Chugach Mountains. In winter its unobstructed western face rises up to catch the sunset, glowing a brilliant ruby red long after the big Hillside homes on its lower slopes have slipped into night.

Anchorage residents recreated below Ruby for decades, accessing Chugach State Park on an old homestead road called the Stewart Trail. Families walked dogs, jogged, berry-picked and ambled into the tundra for panoramic views of the city and the mountains beyond. When it snowed, locals groomed nordic tracks onto the Stewart Trail and taught their children to ski. Though the area was beloved by many it remained something of a hidden gem, a place where those in the know could slip away from city life into the peaceful wildness of the Chugach foothills.

But in the summer of 2015, everything changed. A hiker and his small dog arrived at the entrance to the Stewart Trail to find a man busily expanding an existing vehicle gate with rebar and barbed wire. The hiker described the encounter as follows:

“He had a welding setup there and a bunch of metal… a bunch of rebar and plates, and an acetylene tank. My interaction with him was really short, I walked up to him and said ‘what’s going on?’ and he said ‘I’m building a gate’ or something. And I said ‘Wow, cause I’ve been walking up here since the late 70s or early 80s. I thought it was a public road.’ And he said ‘No, it’s private. And I’m closing it.’ You know he might have said, ‘It’s my land.’”

The man with the acetylene torch was Frank Pugh, and soon his gate was complete. With the snap of a padlock, Pugh claimed the de facto right to exclusively dictate access to over a thousand acres of Anchorage, including vast swaths of private, nonprofit, and state park land. Over the subsequent years, Pugh’s gate has withstood repeated demands from the Municipality to tear it down, the ire and defiance of his neighbors, and the early stages of a lawsuit. The battle for the Stewart Trail has spilled over into a bitter civil war on the Rabbit Creek Community Council, into heated Anchorage Assembly meetings, onto talk radio and into cryptic op-eds published by the ADN. In a 2018 phone call, one exhausted legislator described the situation as an “emotional shitshow.”

The fight for the Stewart Trail is about more than a gate. It has highlighted how decades of compounding errors in city planning have created so much dysfunction that one rogue landowner has been able to seize–and, for years, successfully hold–control over more land than any other individual in the Municipality of Anchorage.

Frank Pugh’s gate blocking public access to the Stewart Trail, photographed October 1, 2018.

Stewards of the State

Ivan and Oro Stewart occupy a middle ground in Alaska history: not quite famous enough for the history books, but so impactful that the ripples of their adventurous lives are still visible throughout the state. Ivan and Oro married in Alaska in 1942, at the height of WWII. According to a 1996 article in the LA Times, the couple was woken during their honeymoon camping trip on Kodiak by American soldiers who mistook them for Japanese spies. Not long after, the Stewarts moved to Anchorage and opened Stewart’s Photo on 4th Avenue. The store remains in business to this day.

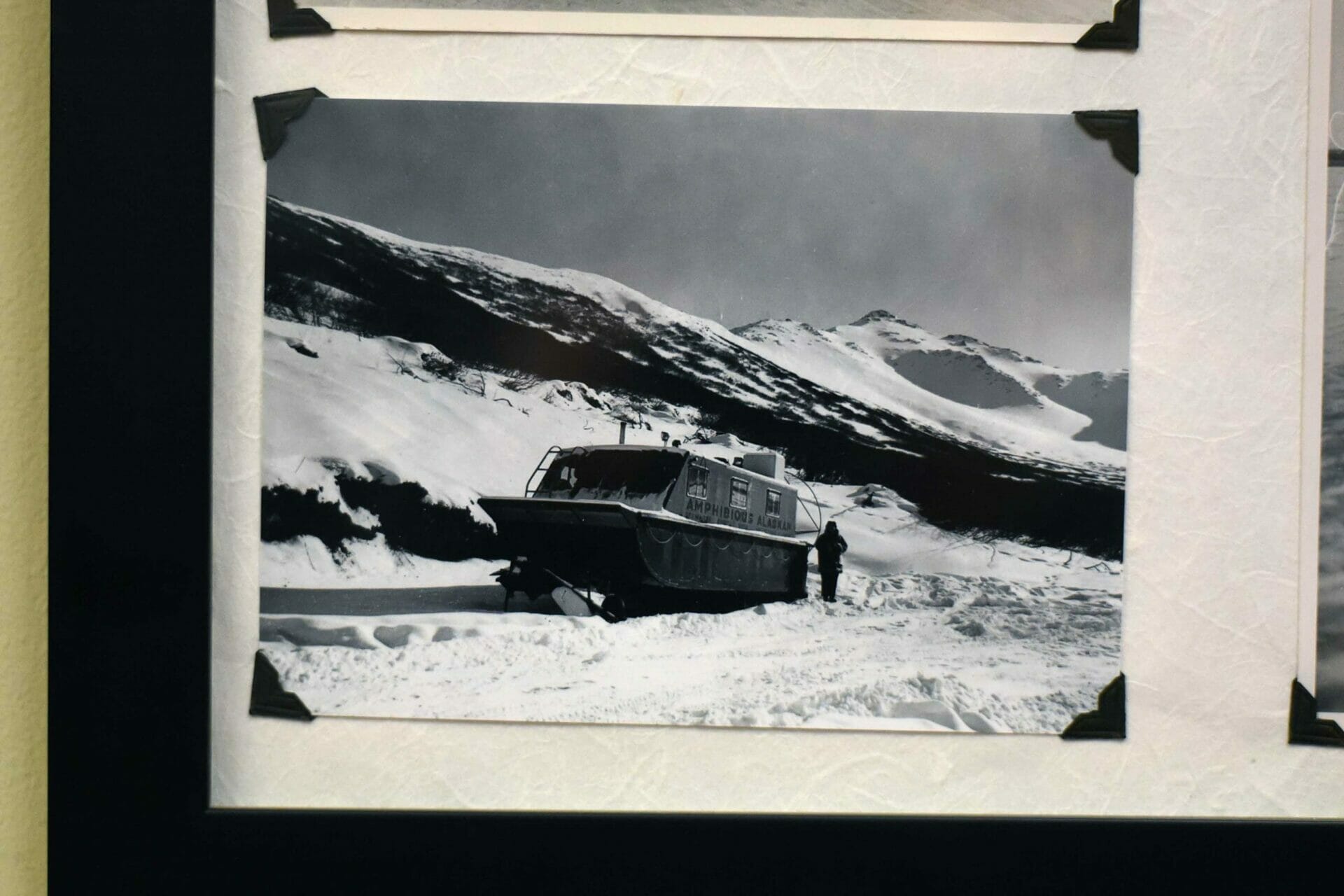

The brilliant and eccentric couple were passionate about geology, and played a key role in the development of Alaska’s jade industry. They traveled the state in an amphibious vehicle, once running 365 miles of the Yukon River in three days. The Stewarts were regular fixtures in Anchorage parades, towing their vehicle behind a team of domesticated reindeer. Around 1960, the couple obtained a homestead tract at the head of upper Potter Valley and began using their amphibious vehicle as a makeshift mountain home. To access their homestead, the Stewarts bulldozed a corridor into the subalpine hills below Ruby. It soon became known as the Stewart Homestead Road.

Ivan and Oro Stewart’s amphibious vehicle on the Stewart Homestead. Photographed at Stewart’s Camera, November 27, 2019.

Ivan passed away in 1986. Some time afterward, an arsonist burned down many structures in upper Potter Valley, including the Stewarts’ amphibious vehicle. Oro was devastated. A vehicle gate was installed across the mouth of the Stewart Homestead Road, but pedestrian access remained unimpeded. Oro passed away in 2002. In her will, Oro Stewart divided her homestead tract between two beloved local organizations, the Alaska Botanical Garden and the Alaska Zoo.

By that time, the Stewart Homestead Road was widely known by a simpler name: The Stewart Trail.

Enter Frank Pugh

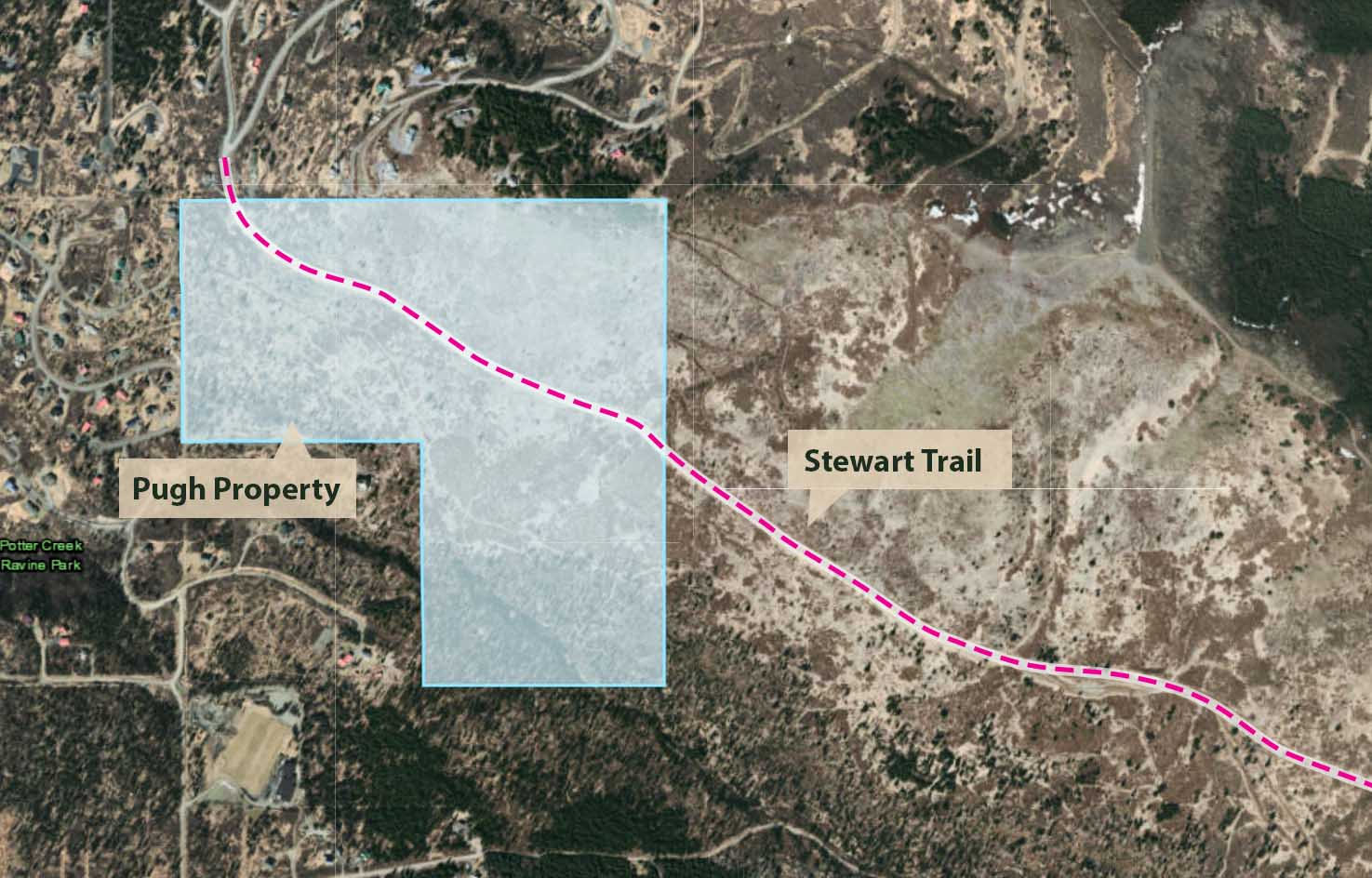

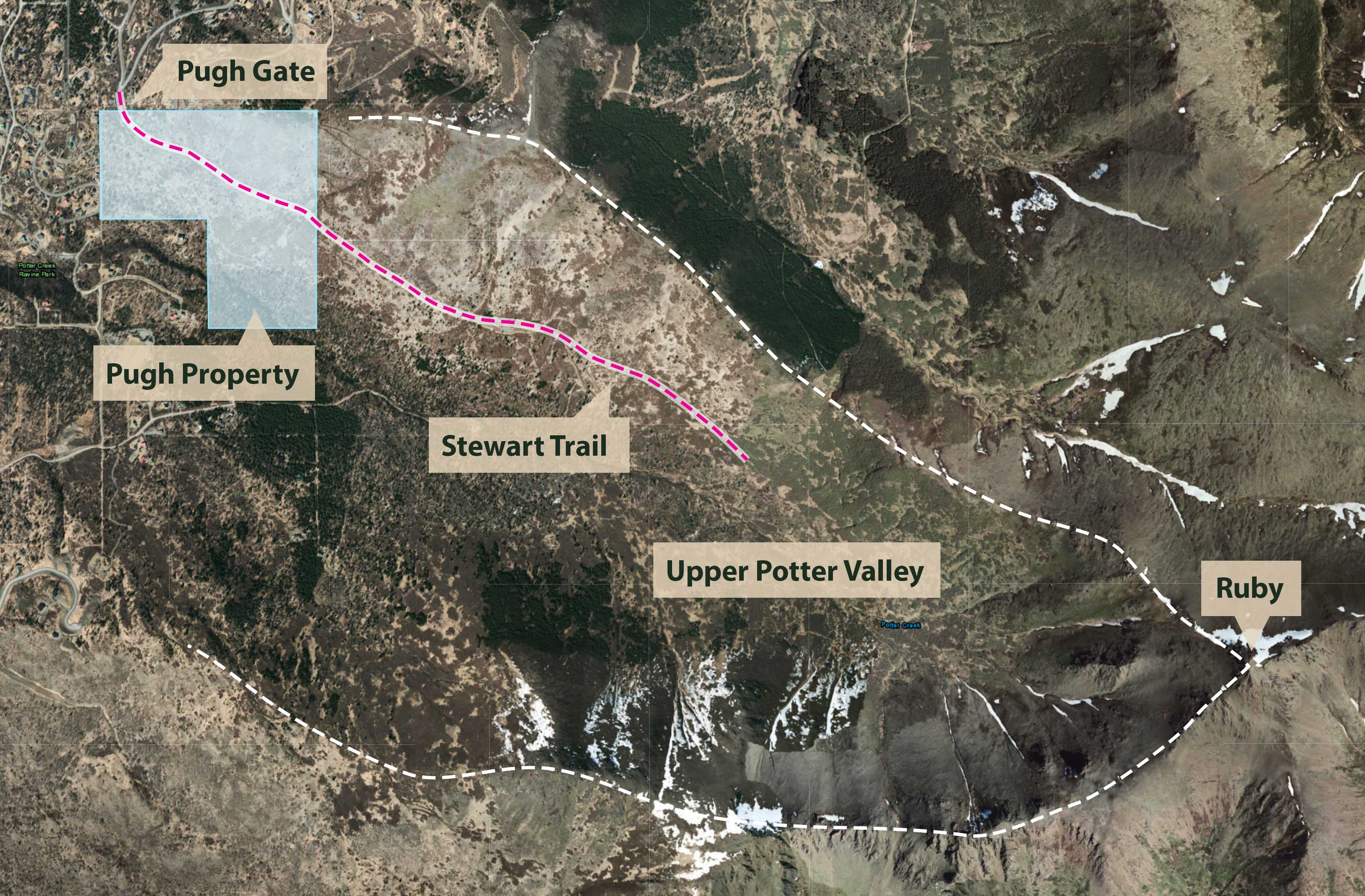

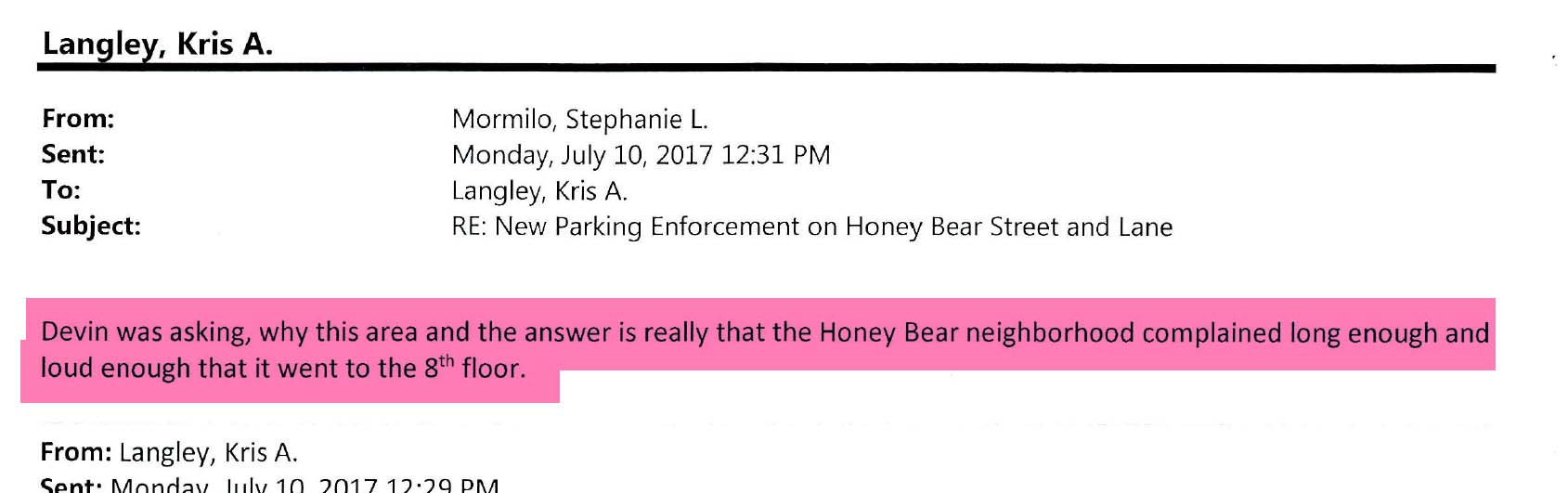

On September 17, 2012, Frank Pugh and wife Oksana Pugh purchased a 120-acre lot in upper Potter Valley formerly known as the Earl Hutchings Homestead. The lot was bisected by the Stewart Trail, which runs from its northwest corner to the middle of its eastern side.

Map showing Pugh Property and the Stewart Trail.

On his LinkedIn profile, Pugh describes himself as a semi-retired drilling engineer with nearly three decades of experience in the petroleum industry. According to his resume Pugh spent two decades working in Louisiana, primarily for Schlumberger, until arriving in Alaska in 2006 to work for BP at Prudhoe Bay. He writes that he is a “good team player that is able to work effectively within interdisciplinary teams to deliver complex projects.” Former coworkers describe Pugh as methodical and precise. “He was sometimes slow,” one former coworker told the Landmine, “but he was careful. He did things right.”

The Hutchings Homestead tract languished on the market for months before the purchase by the Pughs, going through several rounds of sharp price reductions. According to internal MLS system records, the Pughs appear to have paid $360,000 for the 120-acre tract, or only $3,000/acre. At first glance, this would appear to be an astonishing value; buildable lots nearby often sell for $150,000/acre or more. But Pugh’s new acquisition presented major challenges: the bottom portion was encumbered by a wetland and stream, where development would be severely restricted, and the upper areas were steep and exposed. Anchorage outdoor writer and journalist Craig Medred told the Landmine that once, while battling his way down the Stewart Trail during a storm, he had been picked up by the wind and flung through the air into a ditch.

Several Anchorage real estate experts told the Landmine that subdividing the mountainous tract to muni standards and providing code-compliant roads, fire access, septic, water, and other services would be extraordinarily expensive and likely uneconomical well into the foreseeable future. This, they explained, was why the tract had sat on the market for so long and at such a seemingly low price. The lot appeared to have significant value to only one group: users of the Stewart Trail.

When Pugh purchased the lot, nearby residents had little reason to suspect that access to the Stewart Trail would change. If Pugh’s purchase were simply a long-term investment, there would appear to be little incentive to alter the status quo. If he had found some clever way to develop the tract that other Anchorage real estate purchasers had missed, the Stewart Trail would almost certainly have to be brought up to MOA standards and dedicated as a public roadway. Either way, public access would remain.

But in 2015, Pugh abruptly gated the trail. Then came the confrontations and the cameras. And that’s when residents knew something had gone badly wrong.

Mr. Pugh, Tear Down This Wall

Because the Stewart Trail is the only developed public corridor in the area, Pugh’s gate effectively put him in control of access to the the entire upper Potter Valley drainage–an area comparable in size to all of downtown Anchorage. In fact, the land now effectively behind Pugh’s padlock was so vast that it encompassed multiple microclimates, stretching from wooded wetlands by Potter Creek to alpine tundra populated by dall sheep, and finally giving way to the rocky, windswept summit of Ruby itself.

Map showing area made inaccessible by the Pugh gate.

Many nearby residents, some of whom had moved to the neighborhood specifically because of the Stewart Trail, were aghast. Moreover, Pugh’s gate now blocked access to the original Stewart Homestead land now owned by the Alaska Zoo and Alaska Botanical Garden, as well as large tracts owned by the MOA Heritage Land Bank and the State Department of Natural Resources (DNR). The Landmine was unable to determine who first brought the situation to the attention of the Municipality of Anchorage (MOA), but on February 29, 2016 then-MOA Attorney Bill Falsey drafted a letter to Pugh with a clear message: the gate was illegal, and would need to be removed. A portion of the letter reads:

Dear Mr. Pugh,

It has come to our attention that you recently blocked access to the road/trail that leads to the Stewart Homestead property and beyond. Out of necessity, homesteaders built and travelled this road to reach their homesteads. More recently, local residents have used the trail for recreational purposes. An informal survey of the neighborhood reveals that residents have been walking this trail since at least the mid-1960’s…

The Municipality has an obligation to protect the public’s interest in this trail. Therefore, we respectfully request that you remove the barriers you have installed by March 4, 2016.

Falsey followed with letters dated March 2, 2016, and April 20, 2016. The letters are reproduced below.

Letters from the MOA to Frank Pugh

Letters sent from MOA Attorney Bill Falsey to Pugh demanding the removal of the Pugh gate. Click on the thumbnail to read the full letter in PDF format.

Easements: Often Hard, Rarely Easy

In his letters, Falsey writes that the Stewart Trail is open to public use because it meets the qualifications for a prescriptive public easement. As Falsey explains in his March 2, 2016 message to Pugh:

“The public’s consistent use of this trail for the past several decades has created a public use easement across the property. A public prescriptive easement exists when there has been continuous, hostile, and open use by the public over a 10-year period.”

As Falsey notes, easements by prescription are created through public use that is continuous, hostile, and open. These conditions can be summarized as follows:

- Continuous: Use of the easement must be frequent and generally uninterrupted.

- Open: Use of the easement must be visible and apparent to a reasonable property owner.

- Hostile: Hostile use does not require any hostility per se; rather, this means that use of the easement is conducted without permission and does not provide any obvious benefit to the landowner.

Some private property advocates dislike easements by prescription because they diminish a private property owner’s full control of a property. However, the concept has been part of English common law since 1275 and has remained a central part of western property rights regimes since then. Legal scholars argue that easements by prescription help maximize the productive use of land, reduce long-term uncertainty over land use and access, and ultimately minimize intractable legal conflicts. The Stewart Trail is far from the only prescriptive easement in Anchorage, where many trails and roads were built with little regard to official property lines. In fact, if every easement created via prescription on the Hillside were blocked off at once, hundreds of Hillside residents would find it difficult or impossible to reach their homes. Prescriptive easements can be frustrating for private property owners, but necessary for the free movement of people and goods.

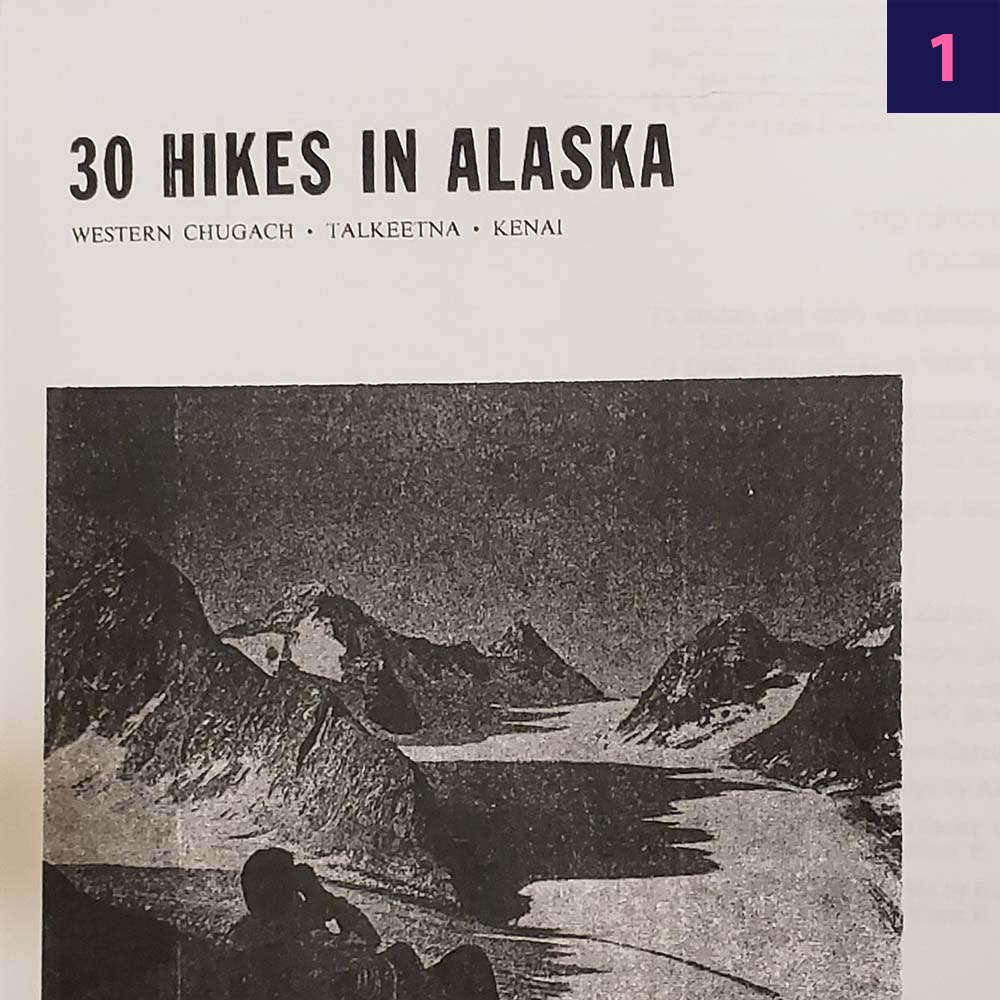

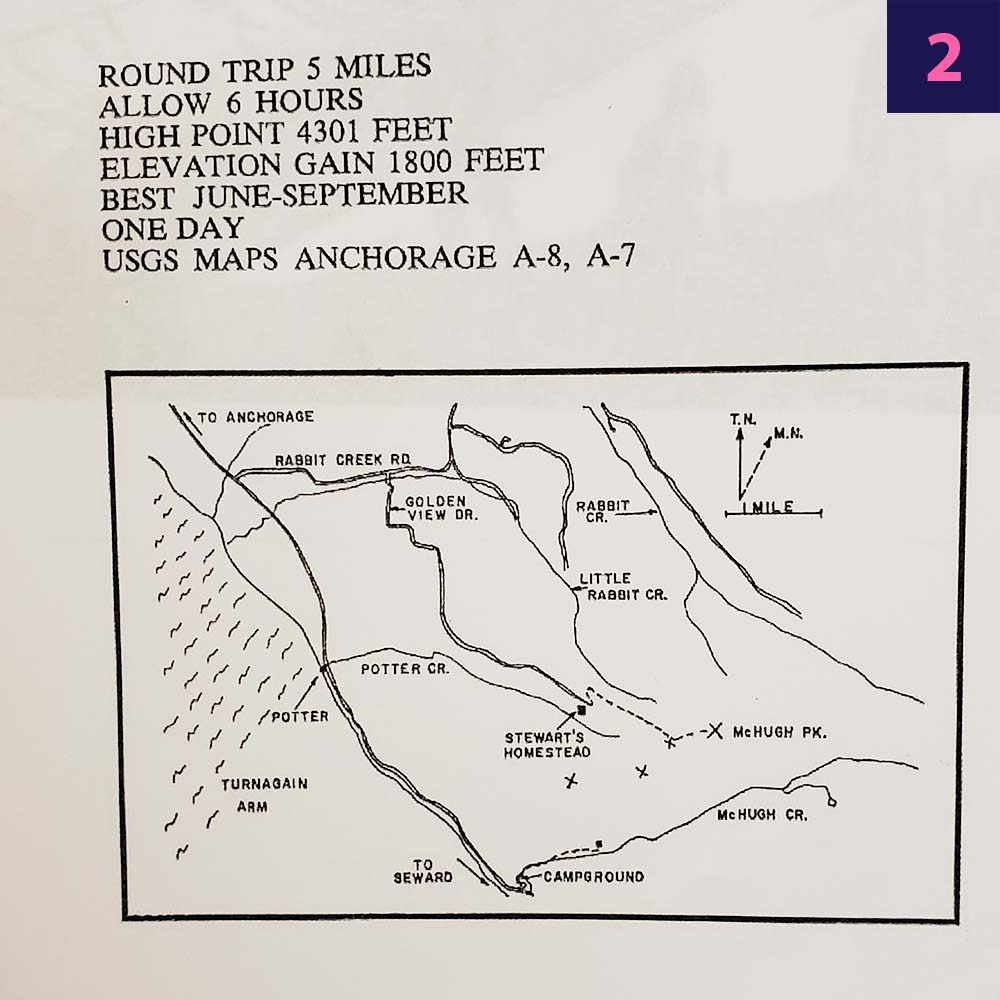

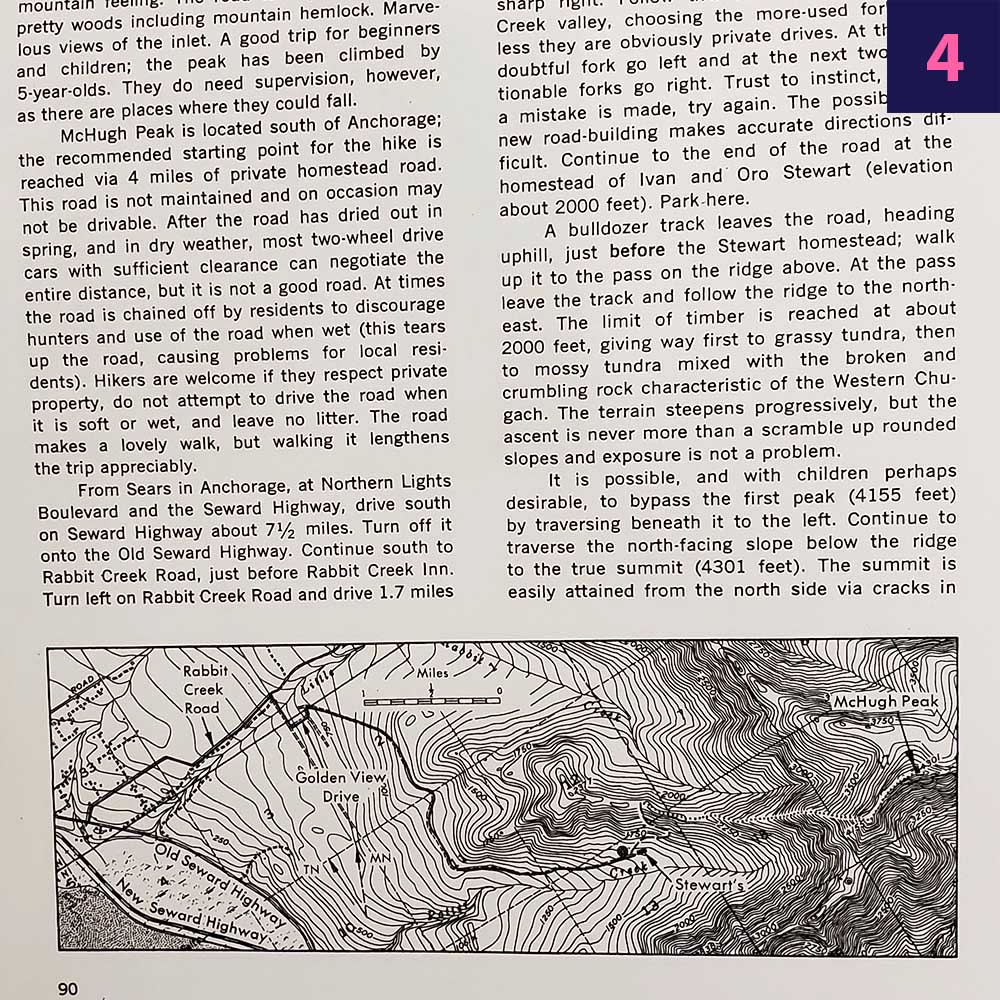

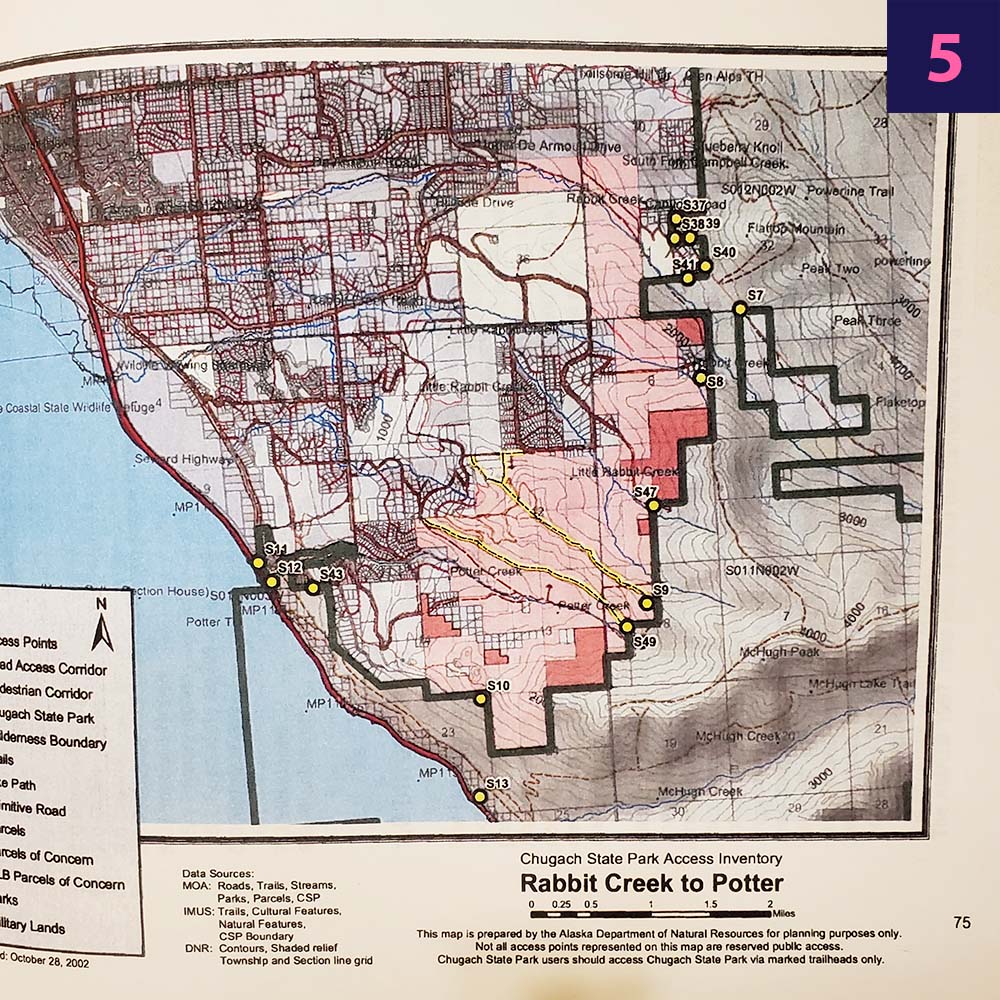

Disputes about whether use of land is sufficiently “continuous, open, and hostile” to create a prescriptive easement can be contentious. But in the case of the Stewart Trail, evidence of historical use seems to be overwhelming. In 1967, the Stewart Trail was featured in 30 Hikes in Alaska as the preferred route to climb McHugh Peak. 55 Ways to the Wilderness, published in 1972, advises readers that “hikers are welcome” and that “the road makes a lovely walk.” Between 2002 and 2010, the Chugach State Park Access Inventory, Rabbit Creek Trail Plan, and Hillside District Plan all refer to the Stewart Trail as a public access corridor. In a 2016 Alaska Trails Survey, over seventy people stated that they had openly used the Stewart Trail for decades. Anchorage residents have thousands of photos of themselves, their friends, and their children using the Stewart Trail in all seasons. And any sighted individual who either visited the Pugh property in person or viewed it via satellite imagery would have plainly seen a well-developed and heavily-used trail crossing it.

Evidence of continuous, open use of the Stewart Trail dating back to 1976. Images 1 and 2: 30 Hikes in Alaska (1967). 3 and 4: 55 Ways to the Wilderness (1972). 5: Chugach State Park Access Inventory (2002).

Any claim that use of the Stewart Trail has not been continuous or open for decades would self-evidently fail the “red face test.” With these two conditions for an easement by prescription clearly met, Pugh made an interesting claim: trail users may have used the Stewart Trail openly and continuously, but did so with express permission of the Stewarts. This meant that the use could not be considered “hostile,” and therefore conditions for an easement were not present. In a September 24, 2018 email to Anchorage Assemblymember Christopher Constant, Pugh states this belief explictly:

“As for Ms. Stewart, based on your comments and the many discussions that I had with people on my property, it is evident that she granted permissive use to many people thus making claims of prescriptive easement null and void.”

The Star Witness

To assess Pugh’s claim that the Stewarts granted permission to individuals to use the trail, the Landmine contacted the Stewarts’ longtime employee and friend Albert Whitehead. Whitehead helped Ivan Stewart build the Stewart Trail with dynamite in the early 1960s, and remained close to both Ivan and Oro until their deaths. As a young man, Whitehead spent long weekends camping on Ruby, watching dall sheep bound between the crags. When Oro Stewart passed away in 2002, Whitehead learned that she had willed him her ranch home on the Park Strip in downtown Anchorage. After a quick call, he agreed to an interview.

The walls inside Whitehead’s home were covered with prints of Alaska paintings, and chunks of jade quarried by Ivan Stewart sat on the windowsills. In the back yard, Whitehead introduced Team Landmine to Star the Reindeer, a descendant of the same herd that Ivan and Oro had paraded through Anchorage decades ago. Whitehead handed out carrot treats and suggested touching Star’s antlers once he warmed up to the new attention. The blood coursing through reindeer antlers, Whitehead explained, causes them to vibrate like a tuning fork.

Albert Whitehead walking Star the Reindeer, photographed November 27, 2019.

Back inside, Team Landmine asked Whitehead whether Ivan or Oro Stewart had ever been concerned with granting permission to traverse the Stewart Trail. Albert’s answer was unequivocal: the Stewarts had never cared about permission to use the trail or cross their lot.

“No, no, no, they never had a problem with people going up there! I was up there in the 60s. We been up there, after Ivan died, we went up there with Oro, people [were] up in there. I don’t recall her telling anyone to leave.

Even after they burnt the houseboat down, I don’t recall Oro saying–when we were up there, we saw people walking or hiking–she didn’t say ‘get out of here.’ It was just ‘Hi, how are you doing?’ that kind of stuff. The usual kind of casual, ‘Alaska Hello.'”

From the other side of the room, Whitehead’s longtime companion Martha interjected:

“She had that old Alaska attitude of everyone helps everybody.”

The Trail Goes Downhill

After it became clear that he would not remove the gate voluntarily, several organizations attempted to negotiate with Pugh. Local conservation giant Great Land Trust (GLT) commissioned an assessment of the easement, and Pugh indicated that he would entertain an offer. GLT has negotiated major land deals in the Anchorage area, including a $7.4 million purchase for South Anchorage’s 60-acre Campbell Creek Estuary Park. But GLT determined that the Stewart Trail easement had little monetary value and Pugh balked at their offer, which was reportedly in the low tens of thousands of dollars. Pugh met with the MOA to discuss a land swap, but rejected the proposed deal. A group of residents banded together and offered to pay for an easement, but Pugh reportedly told them they did not have enough money.

Meanwhile, the situation on the Stewart Trail was devolving into a tense standoff. Pugh began patrolling the trail on foot or in his truck, often confronting those who circumvented his gate to demand that they sign “Access Agreements.” Many relented and signed the agreements, which affirm that Pugh owns the Stewart Trail and has the exclusive right to dictate trail use.

But others refused. Some noted that signing the access agreement would make use of the Stewart Trail “permissive.” Just as prescriptive easements are created by non-permissive “hostile” use, they can also be eliminated if use eventually becomes permissive. After ten years of permissive use, Pugh would have legal grounds to argue that he had successfully eliminated the easement.

Some trail users declined to engage with Pugh, while others began carrying copies of the MOA’s letters stating the trail was public. Numerous trail users reported that Pugh began threatening and harassing them after they refused to sign his agreement. One longtime local resident and trail user told the Landmine that Pugh chased him down the trail, yelling “Don’t come on here! Don’t come on here!” Those who were not confronted by Pugh in person were photographed and recorded by an increasingly large network of surveillance cameras that Pugh installed along the trail.

Surveillance camera operated by Frank Pugh on the Stewart Trail. Photographed October 1, 2018.

In emails, Pugh frequently refers to unauthorized trail users as “trespassers” engaged in criminal trespass. But there is a problem with this characterization: the Anchorage Police Department (APD) is a department of the MOA, and the MOA had determined that the Stewart Trail was public. In an October 10, 2018 call, APD spokesperson MJ Thim told the Landmine:

“Overall this is a civil matter [as opposed to criminal] and we will respond if there are any public safety matters, but this is a civil matter and that’s how we’re treating it.”

Though Pugh has repeatedly called APD to report “trespassers,” noone has faced criminal charges for using the trail. Pugh could bring the matter to civil court, but as Anchorage Assemblymember Christopher Constant told the Landmine, an incredulous judge could tell Pugh that the trail is public and order him to remove the gate. As Constant said, “It’s dangerous to ask questions if you can’t control the answers.”

Without support from the police, and perhaps suspecting an unfavorable outcome in civil court, Pugh resolved to defend the trail alone. Pugh began prominently displaying a large revolver on his hip, and reportedly began driving close behind nervous hikers with his truck. Some residents began openly wondering whether the situation could tip into violence.

This land is our land, this land is our land

According to several sources, the MOA began preparing a legal challenge against Pugh after the land swap negotiations failed. But by mid-2017, those efforts had stalled. Some noted that the city was overwhelmed with a property crime wave, and stolen cars took precedence over stolen mountains. Others suggested that the MOA had grown to believe that a judge or jury could perceive a lawsuit pitting the municipality against a single landowner as a “David and Goliath” situation. But in a January 2, 2019 email to the Landmine, Municipal Attorney Rebecca Windt Pearson offered another explanation: “The Municipality has not proceeded to litigation on this issue primarily because, as noted, the Municipality lacks land management authority and resources in this area.”

The reason that the MOA claims to lack authority over the Stewart Trail area is that much of the trail lies outside of the MOA’s “parks service area.” When the boundaries for the parks service area were drawn, a diagonal line across the Chugach foothills excluded portions of Bear Valley, Stuckagain Heights, Potter Valley, and other portions of the upper Hillside–including much of the Stewart Trail. Those who happen to live outside the parks service area, including some of Anchorage’s wealthiest residents, enjoy full access to Anchorage parks but pay no taxes to support them. Conversely, the MOA is unable to spend public parks funding outside of the service area.

In late 2017, Anchorage Assemblymember John Weddleton proposed an ordinance bringing the entire Hillside into the parks service area. To pass, the ordinance needed to be approved at the ballot box by two groups: members of the current service area, and Hillside voters currently living outside of the service area. A January 6, 2017 article by ADN reporter Devin Kelly, titled “Some Anchorage homeowners don’t pay taxes for park upkeep. An assemblyman wants to change that.” cites Weddleton’s position as follow:

“‘For most of the city, it’s a no-brainer out of fairness’ that the entire Hillside should pay taxes for park maintenance, Weddleton said. But a ‘huge amount of self-interest’ has been generated among Hillside homeowners over the years, he said. …‘The problems they’re facing with people parking in their streets and using private property will not stop.’”

John Weddleton speaks at an Anchorage Assembly Meeting, January 29, 2019.

In the April 2017 election the measure was overwhelmingly approved by voters in the current park service area, but was rejected by residents of the upper Hillside. In a January 1, 2019 phone call with the Landmine, Weddleton said the proposition had failed because those outside of the service area wanted to continue avoiding city park taxes, and wanted to keep outsiders out of their neighborhoods. Weddleton added, “that traffic’s coming anyway. We have no way to create parking, or pick up the trash. But the people are coming anyway.”

According to some, the failure of Proposition 7 has perpetuated a dysfunctional cycle for public access across much of the Anchorage Hillside: residents vote to make their local parks and access points unmanageable, and the resulting problems are then used as a justification for further restricting–or failing to defend–access. Over time, public access to parks becomes heavily concentrated at a few locations, such as Glen Alps, and overcrowding at those sites is then cited as a cautionary tale by those seeking to stifle access elsewhere. This self-fulfilling cycle results in an undersupply of access points to the park, and causes chronic overcrowding at the access points that do exist. In an August 22, 2019 phone call, Chugach State Park Superintendent Kurt Hensel told the Landmine, “To me it’s really frustrating to have such a great, big awesome park out there, but have limited parking and we have to turn people away to the third largest state park in the country.” Hensel remarked that planners should work to serve the general public, and not just Hillside residents anxious about the public entering their neighborhoods.

This dynamic is clearly at play in the battle for the Stewart Trail. In a January 30, 2018 email obtained by the Landmine, Pugh warns a group of local residents about the consequences of re-opening the trail:

“If you are like me and you want Potter Valley to remain a relatively quiet neighborhood environment unencumbered from being a ‘Public Access Point’ like Flattop then we should work together. The alternative is that the landowners could easily work with the Municipality to ensure that a ‘Public Access Point’ is established through Potter Valley along with all the vehicles, people, dogs, noise, and crime likely to follow but this is not our preference.”

Grumpy Bear

Problems with public access have proliferated across Chugach State Park, from the South Fork Eagle River Trailhead to Mt. Baldy, Ram Valley, and Glen Alps, but perhaps no location exemplifies the difficulties providing park access as well as the “Honey Bear” trailhead in upper Bear Valley. This trailhead is the only designated public access for a vast swath of Chugach State Park stretching between McHugh Creek and the Rabbit Lake Trailhead. Though tens of thousands of Anchorage residents live on the foothills below this belt of parkland, the Honey Bear trailhead can accommodate only five vehicles.

The Honey Bear parking lot was platted in the early 2000s as a condition for continued private development of upper Bear Valley. The local HOA agreed to create a small public parking area in the cul-de-sac at the top of Honey Bear Lane, dedicate an easement to Chugach State Park, and maintain the roads and parking area. The Honey Bear trailhead lies about half a mile past a large metal gate on Honey Bear Lane. Residents were forbidden from turning the neighborhood into a gated community because the streets are public, but the camera-studded gate–and its message to visitors–remains.

Gate on Honey Bear Lane, photographed November 29, 2019.

The Honey Bear lot quickly created problems, both for would-be trail users and nearby residents. The trailhead provides quick access to a scenic alpine shoulder of McHugh Peak and some of the best blueberry picking around Anchorage. Once word got out, demand quickly exceeded the capacity of the tiny parking area. Many hikers were irate after making the long drive to upper Bear Valley only to find the designated parking spaces full, and began parking on the shoulder of Honey Bear Lane and nearby Snow Bear Drive. Meanwhile, HOA members suddenly found themselves financially responsible for an increasingly popular de-facto state park trailhead. In 2012, the HOA requested a $218,000 state grant for road improvements, claiming that it could no longer afford to maintain its roads due to increased traffic. The legislature approved $100,000. Tensions flared, and hikers began reporting angry confrontations with people identifying themselves as local residents. Cars were keyed. One group of hikers began referring to the trailhead as “Grumpy Bear.”

Documents obtained by the Landmine show that, starting in 2016, residents began a concerted effort to block members of the public from parking in the neighborhood. According to an email from MOA Traffic Safety Division Manager Kris Langley, someone installed illegal signage around the trailhead, at times using MOA sign posts:

In a series of emails sent between May 28 and June 23, 2016, Stolle Subdivision board member Dan Toomey requested that the MOA allow the local HOAs to gate nearby Snow Bear Drive and permit residents to “assist in parking control at the Park access point.” Toomey states a desire to “limit parking” to the approved spots at the trailhead and cites documented instances of crime and violence at the end of Snow Bear Drive.

Citing precedent and practicality, Fire Marshall Cleo Hill and representatives from the Traffic Department refused to approve the gating of a public road. An internal June 13, 2016 email from Traffic Safety Division Manager Langley states, “I believe our position has been consistent on the gating of public roads: Answer = No.” However, in a message later that day to Fire Marshall Hill, Langley speculates that their decision may be overruled “from above”:

Directions “from above” didn’t alter the MOA’s rejection of the proposed gate, but in late 2016 the MOA Traffic Department announced an ambitious new signage program along several upper Bear Valley streets, including Honey Bear Lane and Snow Bear Drive. In June 2017, custom “No Parking” signs citing AMC 90.30.040 were installed along the roads. On June 20, 2017, APD issued a press release detailing the new parking restrictions. ADN and KTVA ran articles announcing that parking on both sides of the roads was now illegal. Violators would be issued $20 tickets.

Despite the public announcements, documents suggest uncertainty and lingering questions about the accuracy of the new “No Parking” signs. The stated reason for the parking ban was the width of the streets: AMC 90.30.040 requires that 20 feet of roadway be kept clear for vehicle traffic. But in a May 7, 2018 email to a member of the public, Langley writes that, despite the “No Parking” signs, parking would still be legal if a driver could find a way to leave 20 feet of roadway clear:

According to Langley, Honey Bear Lane was a public street “open to the appropriate legal use by any person,” and parking on the shoulder was no more or less illegal than parking on the shoulder of any Anchorage road of equivalent width. In a July 2017 email, Langley suggests that because there was little precedent for the signs, it was unclear whether a ticket issued on Honey Bear Lane would actually hold up in court.

So why had Honey Bear received so much special attention? ADN Reporter Devin Kelly asked the Traffic department that exact question in July 2017. It is unclear what answer Kelly received, but documents suggest that Traffic had their own internal answer: directions “from above” had come down after all.

At some point in 2016 the situation had reached the 8th Floor of City Hall, which houses the offices of the mayor and city executives. In an internal email dated July 10, 2017, MOA Traffic Engineer Stephanie Mormilo writes that Honey Bear residents had complained “long and loud enough” to elevate the issue to the highest levels of local government:

Langley had previously made the same claim in an email on June 15, 2017, writing that “The situation on Honey Bear was generated by contacts to the 8th Floor at [City Hall].”

On November 29, 2019, the Landmine drove to the Honey Bear parking lot. The wind howling through the mountains threatened to push our vehicle off of the icy streets, and the windsock at one resident’s helipad blew parallel to the ground. We had been told that the HOA occasionally plowed snow into the trailhead cul-de-sac’s fire truck turnaround to discourage parking by hikers. Sure enough, small piles of snow had already been mounded in front of the “No Parking” signs. Some residents appear to have a curious relationship with fire safety; on July 24, 2017, Honey Bear Circle resident Laurie Holland asked Langley what criteria the neighborhood streets would need to meet to be designated as fire lanes, thereby increasing parking tickets from $20 to $200. Langley replied that the streets were not fire lanes.

Today, the only message at the trailhead kiosk was a computer printout reading “THERE IS NO LEGAL PARKING OUTSIDE OF FIVE DESIGNATED SPOTS.” The sign went on to inform hikers of overflow parking down the hill outside of the community’s gate, and ended with a strange admonition: “DON’T BE EVIL.”

Sign at the Honey Bear parking lot, photographed November 29, 2019.

Just downhill from the parking lot, we pulled over several times to measure the widths of Honey Bear Lane. The measuring tape thrashed in the wind, but with one of us on each side of the road we were able to wrestle it to the ground. It was trivially obvious that several spots on Honey Bear Lane would allow vehicles to pull fully off of the road surface and onto the shoulder. At least one section of road corridor was wide enough that we reached the “STOP” message at the end of our 35-foot measuring tape.

Measuring road widths on Honey Bear Lane, November 29, 2019.

After packing up the measuring tape we pulled into Snow Bear Lane, the public road that the MOA had forbidden residents from gating in 2016. Just past the first private drive, we immediately noticed several large boulders blocking vehicle access on the roadway. About fifty feet beyond the boulders, an offical-looking street sign read “NO TRESPASSING. PRIVATE PROPERTY.” Below it was an illustration of a camera, and the words “NOTICE: THIS AREA IS UNDER 24 HOUR VIDEO SURVEILLANCE.”

Roadblock on Snow Bear Lane, photographed November 29, 2019.

Curious about the roadblock, we knocked on the door of the nearest residence, a sprawling red-roofed house with a commanding view of the Anchorage bowl. A man answered the door. When we asked about the boulders, he told us “I don’t know who put them there.” When we told the man we were working on a story, he abruptly said “I bet you’re for trespassing on private property.” He then stated he would not be answering any more questions.

Mattanaw’s Peak

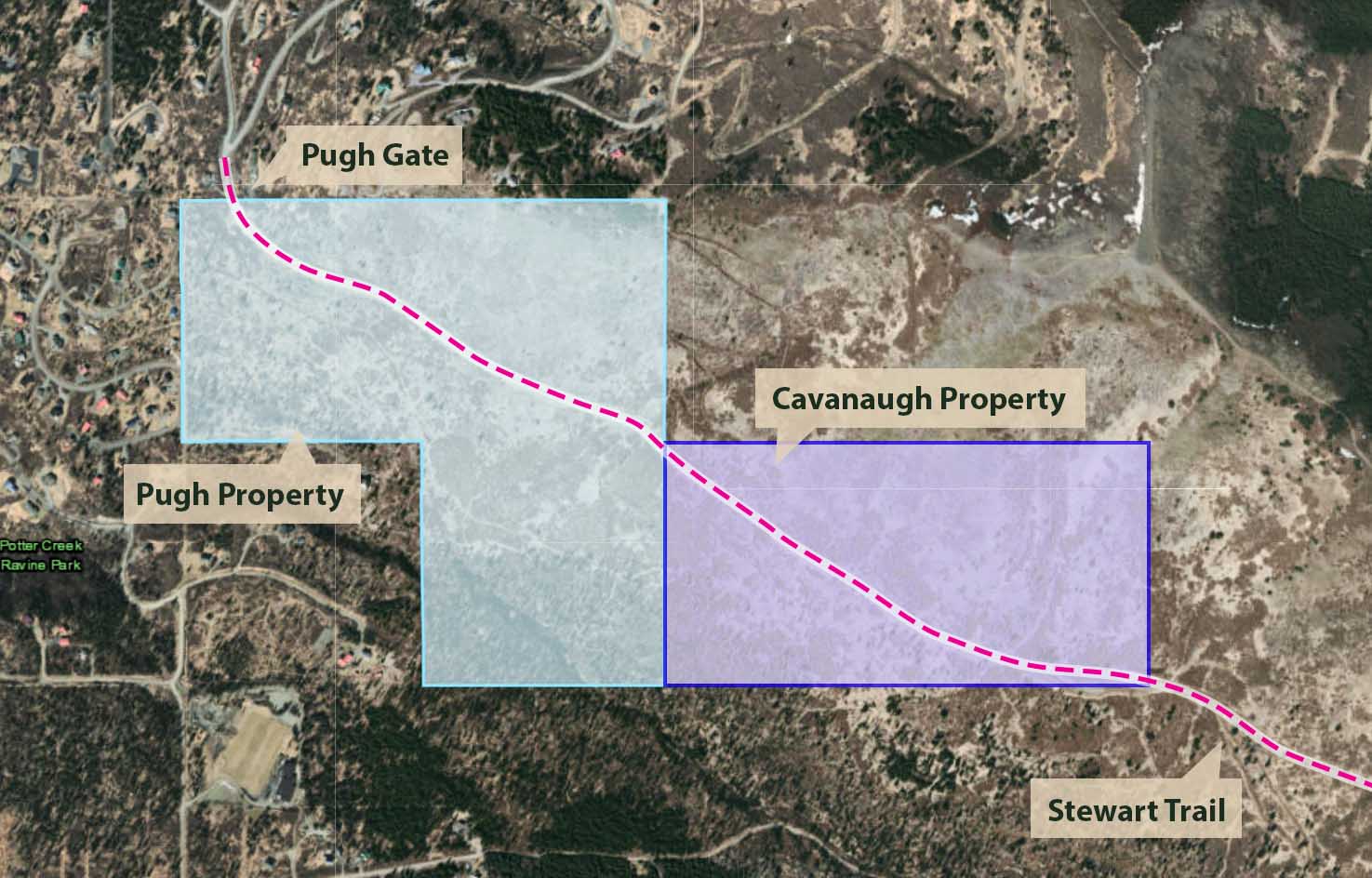

In early August 2017, a new figure emerged on the Stewart Trail. Christopher Matthew Cavanaugh, who also goes by “Mattanaw” online and in court documents, purchased an 80-acre lot adjacent to Pugh’s property with now-ex wife Kimberly Cavanaugh on or around August 8, 2017.

Map showing Cavanaugh property and the Stewart Trail.

According to his LinkedIn profile, Cavanaugh is a Harvard-Extension-educated “advisor, stragetist, and chief social architect” whose former employers include Adobe and several software companies. On the question-and-answer website Quora, Cavanaugh describes himself as a “writer, philosopher, psychologist, polymathist. Vegetable, coffee and fitness junky.” He is a card-carrying member of Mensa (“The High IQ Society”), and frequently writes about the burdens and challenges of high intelligence. These include difficulty communicating with those of more pedestrian aptitudes. “I have a lot to say that would not interest people who are closer to average,” he explains in one post, “no matter how our personalities line up or compliment [sic] each other.”

The Cavanaughs drove their RV up the mountain and parked it in the middle of the Stewart Trail, blocking the trail and forcing hikers to detour around it. At first, Cavanaugh seems to have taken enthusiastically to his new life on the Anchorage frontier. His blog includes excited entries about the wind, problematic winterbears, moose, and ease of access to wilderness in Anchorage. In one Instagram post detailing an attempt to climb Ruby, Cavanugh explains that he has decided to name the peak “Mattanaw’s Peak,” after himself.

But Cavanaugh almost immediately developed a hostile relationship with Stewart Trail users. Hardly a month after purchasing the land, Cavanaugh began posting his own “NO TRESPASSING” signs. Cavanaugh’s signs demand that trail users exit the property and incorporate clip art of handcuffs, a person being arrested, and a person gripping the bars of a prison cell.

Signage on the Stewart Trail posted by Christopher Matthew Cavanaugh, photographed October 14, 2018.

Cavanaugh seems to have become particularly frustrated by the Anchorage Police Department’s refusal to cite Stewart Trail users for trespass, and started taking matters into his own hands. Cavanaugh developed his own network of cameras to surveil trail users, and began confronting people on the trail.

On August 18, 2018 he posted a photo of himself on the Stewart Trail on Instagram wearing a chest-mounted Glock 20. In other posts, Cavanaugh and his friends joke about scattering shells on the Stewart Trail and painting crosshairs onto his signs to intimidate trail users. Even in a town where comfort with firearms is the norm, some residents found Cavanaugh’s posts–and his increasing desire for confrontation–unsettling. In June 2019, Cavanaugh accosted Team Landmine and local journalist Craig Medred while walking on the Stewart Trail to prepare for this story. Cavanaugh emerged from the bushes yelling “Go away!” while waving a GoPro camera, and then attempted to block the trail with his vehicle.

Christopher Matthew Cavanaugh confronts Alaska Landmine Editor-in-Chief Jeff Landfield, Anchorage journalist Craig Medred, and the author on the Stewart Homestead Trail, June 2019.

On June 19, 2019, the Anchorage Daily News published a cryptic editorial by Cavanaugh titled “Anchorage’s never-ending crime prevention loop.” In the article, Cavanaugh excoriates the Anchorage Police Department for allegedly enabling criminal behavior, and expresses frustration at the time he has had to spend covertly recording and “catching” trail users. At the end of the article, Cavanaugh claims to have “evidence of likely corruption within Anchorage up to perhaps the state level.” Neither the alleged corruption nor the nature of the evidence are specified.

“Welcome to Rabid Creek”

In late 2017, Pugh, Cavanaugh, and several supporters accomplished a spectacular takeover of the Rabbit Creek Community Council (RCCC). Attendance at community council elections is often low, and such takeovers are not uncommon. Opponents tend to view them as hostile coups, while others simply see the messy process of local democracy in action. In early 2018 Pugh became Chair of the RCCC, and Cavanaugh became Vice-Chair.

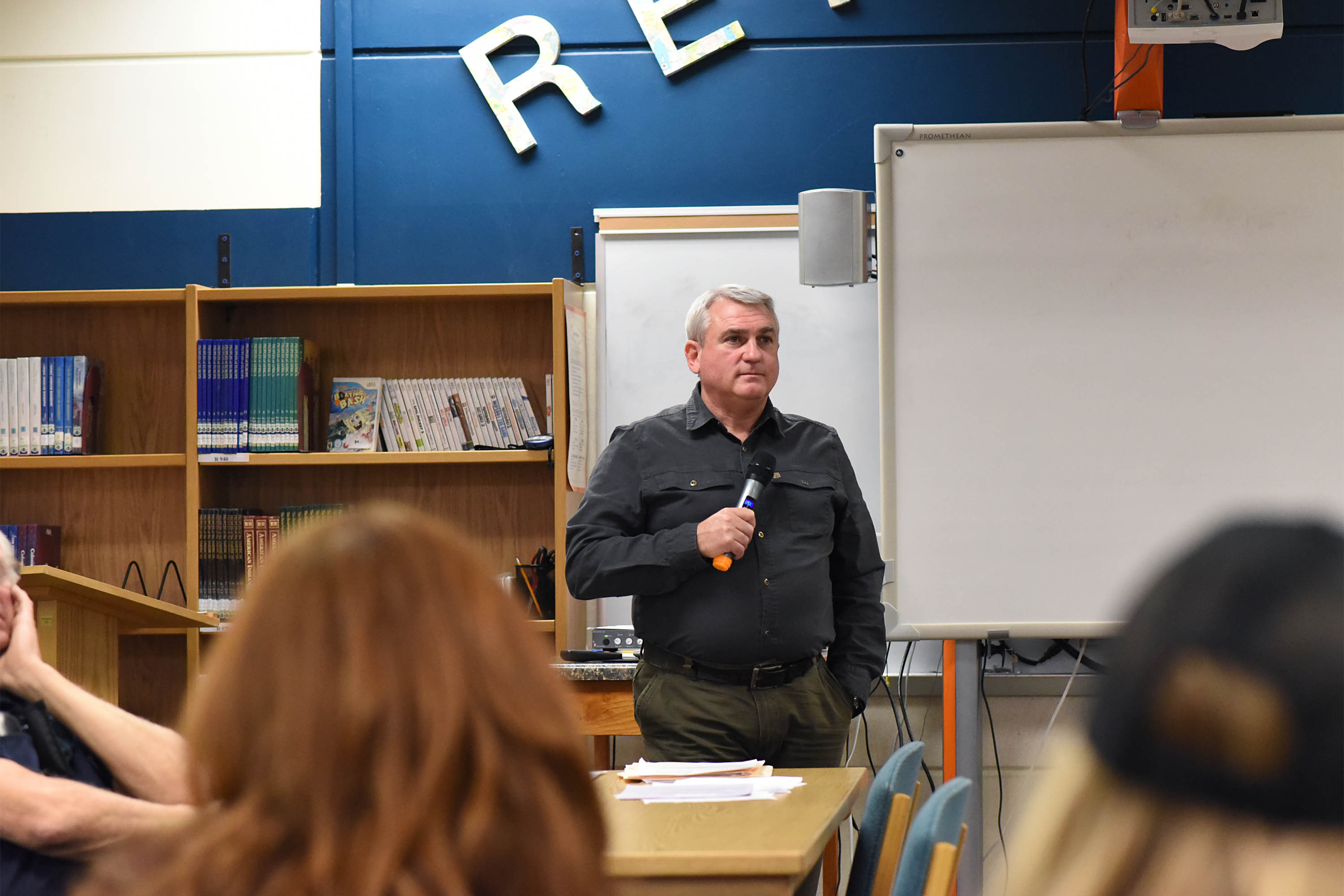

On October 11, 2018, Team Landmine attended the monthly RCCC meeting at Golden View Middle School. Pugh, who repeatedly declined to comment for this article, stood at the front of the downstairs meeting space under a giant banner reading RESPECT. Cavanaugh sat at a table, apparently taking notes. Pugh took the mic and, in a thick southern accent, began.

Frank Pugh leads a Rabbit Creek Community Council Meeting, October 11, 2018.

Almost immediately, the meeting careened out of control. People darted in and out of small huddled groups, yelled, and talked over a grimacing Pugh. At one point, Pugh invited members to voice any opposition to an obscure proposition, which he identified only by number and refused to describe. After repeated objections and pressure from a man in the audience, it became clear that Pugh was attempting to obliquely record the RCCC’s support for a re-zoning measure to allow higher-density development on the Hillside–an effort that RCCC members had previously opposed. When the Team Landmine tried to speak to one attendee about Pugh’s tactics, she squinted at us and whispered, “It depends. Whose side are you on?”

It was not evident what Pugh and Cavanaugh hoped to accomplish by taking over the RCCC. One individual speculated that Pugh wanted Potter Valley to secede from the RCCC and join the Bear Valley Community Council. But that would require a vote of the Anchorage Assembly, and one Assembly member told the Landmine that secession attempts would be dead in the water. Others thought that Pugh wanted to change municipal policy related to trail development and park access requirements for new developments. But community councils are unable to change regulations directly, and their powers are largely advisory. By this point, many influential people in the broader Anchorage community had become aware of the bizarre drama unfolding on the Stewart Trail and at the RCCC. Some doubted that Pugh’s RCCC had the political capital to affect public policy at all.

However, it was clear that the RCCC meetings under Pugh’s leadership had accomplished one thing: a resistance had crystallized. The man in the audience grilling Pugh about his handling of the re-zoning issue was Bert Lewis, an Anchorage fisheries biologist who had already begun organizing a neighborhood effort to reopen the Stewart Trail. And at the back of the room, well-known mountain runner and former RCCC Co-Chair Nancy Pease appeared to be the nucleus of another small group of opposition. According to one attendee, Pease had become a prominent advocate for trails and park access in city planning efforts. Some developers appreciated her work, and highlighted trails that Pease had pushed for in their real estate listings. Others, like Pugh, saw her as a threat.

Team Landmine left the meeting early. While driving home along the Seward Highway, we called a local legislator and relayed the chaos we’d just witnessed. The legislator laughed. “Welcome to Rabid Creek,” he said.

War and Pease

In the fall of 2018, Pease applied for a position on the municipal Board of Adjustment, an obscure but powerful board that can override land use decisions made by other municipal boards and commissions. The position requires confirmation by the Anchorage Assembly, and Pugh was determined to stop it. Pugh and several men arrived in person to the September 25, 2018 Assembly meeting and sat in the lower right section of the Assembly gallery.

Several days before the Assembly meeting, Pugh had sent Nancy Pease a letter titled “Order to Stay Away from the ‘Pugh’ Property.” The Assembly, mayor’s office, RCCC, Senator Cathy Giessel, and others were cc’d. Pugh had also written to the Assembly alleging repeated trespass by Pease, “unlawful behavior” and “serious concerns about Ms. Pease’s ethical integrity and conflicts of interest.” Shortly before the meeting, Christopher Matthew Cavanaugh had emailed the mayor’s office, Assembly, and others calling Pease a “criminal” and accusing her of “criminal trespassing behaviors.”

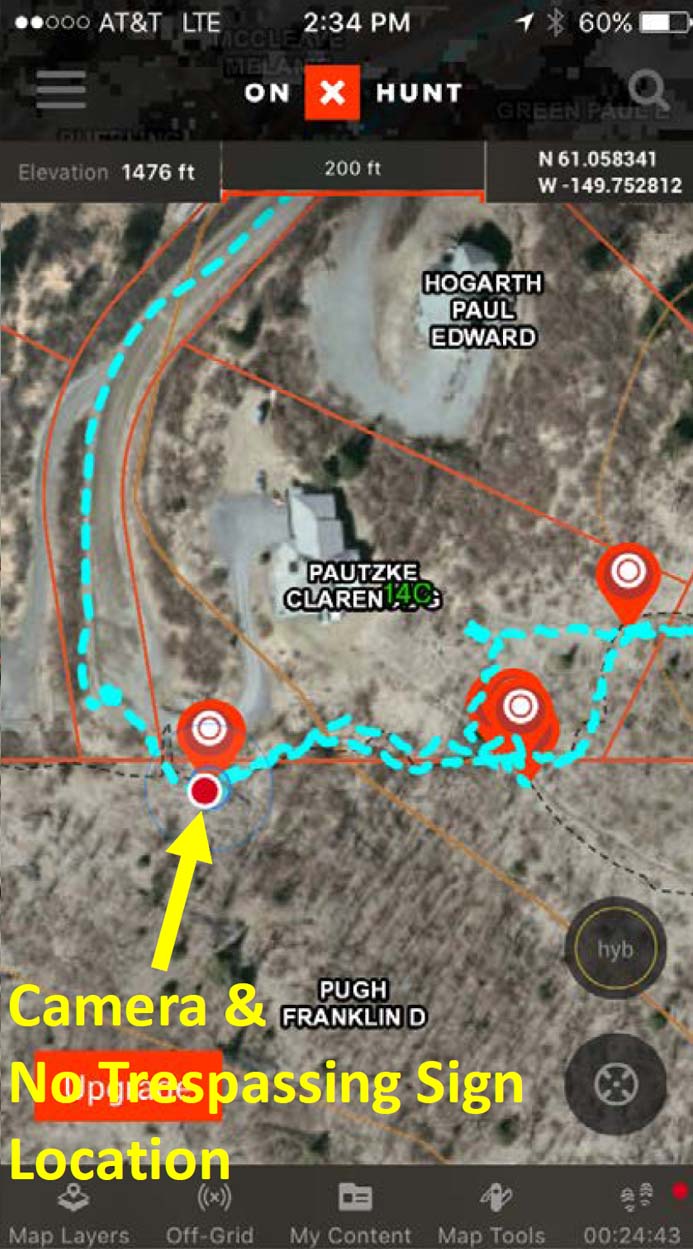

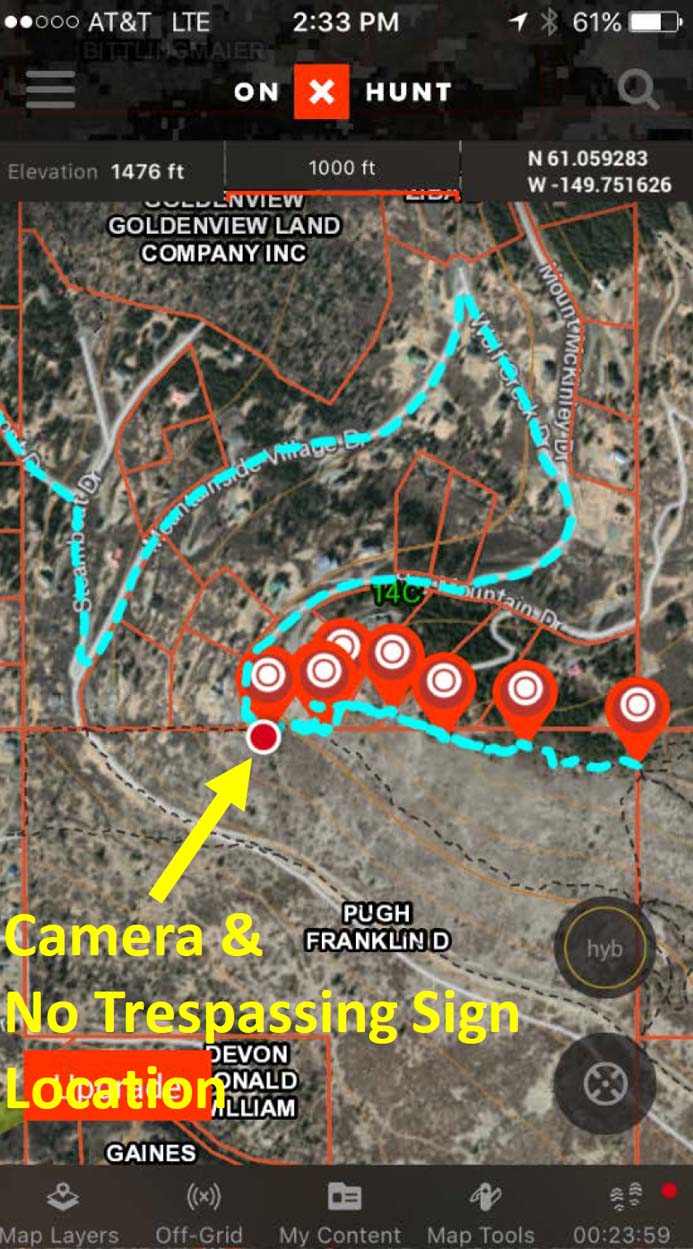

To support his claims, Frank Pugh submitted game camera photos that appear to show Nancy Pease and her brother, Thomas Pease, circumventing Pugh’s gate on a side trail to reach the Stewart Trail. By submitting the photos to the Assembly Pugh entered them into the public record, revealing the tools he employs to record and track those who use the Stewart Trail. Pugh uses the onX Hunting App (“The #1 GPS Hunting App“) to manage a large network of Stealthcam game cameras, some of which are clearly visible and some which are partially hidden behind trees and bushes.

Locations of several Stealthcam game cameras operated by Pugh. Courtesy Anchorage Assembly records.

To establish the identity of Nancy and Thomas Pease in his photographs, Pugh attached an online article from the Alaska Sports Hall of Fame titled “Queen of the Mountain.” The article includes a photo of Nancy Pease, and summarizes her achievements in the competitive mountain running community. It reads, in part:

Pease’s resume is legendary. Nine-time champion and record holder at Crow Pass. Five-time champion and record holder at Bird Ridge. Six-time champion and record holder at Mount Marathon from 1990-2015. Given all of that, it’s tempting to call Pease the Queen of the Mountain, but that would be shortsighted. Sometimes she reigned supreme over the men too.

Several Assembly members spoke in favor of Pease, citing her experience in land use issues and strong work ethic. After a brief discussion, the Anchorage Assembly voted unanimously to confirm Pease. Pugh, flanked by his supporters, left the building.

Bombs on the Hillside

Eventually, the neighborhood had had enough. Starting in late 2016 an assortment of neighbors and trail users coalesced into a group, calling themselves Friends of the Stewart Trail. In 2018, as it became increasingly clear that the Municipality and Great Land Trust’s negotiations with Pugh had failed, the group began fundraising for a potential legal challenge against Pugh and Cavanaugh. On September 2, 2018, Friends of the Stewart Trail announced via email that they had initiated a lawsuit:

“The Friends of the Stewart Public Trail has resolved to commence litigation to confirm the non-motorized public access trail rights to the historic Stewart Homestead Road, and to remove the gate blocking access to it.”

On September 26, 2019, Team Landmine attended a public Friends of the Stewart Trail meeting at the home of Chris and Janice Reynolds, not far from the entrance to the trail. Smoked salmon and cans of King Street hefeweizen sat on the table, and an aged golden retriever ambled between guests in the packed living room. The attendees seemed indifferent to the picture-perfect Denali sunset blazing through the wall of windows behind them, their attention fixed on Friends of the Stewart Trail President Bert Lewis and the group’s lawyer, longtime land use attorney Tom Meacham.

Meacham quickly summarized the state of the lawsuit: Friends of the Stewart Trail had grown to over a hundred members, and had assembled a great quantity of notarized statements and other documents establishing decades of trail use. Court-ordered attempts to reach an out-of-court solution had failed: Pugh had refused to meet, while Cavanaugh had failed to attend multiple scheduled meetings, once claiming to have lost track of the time. A tentative trial date had been set for June 22, 2020.

After Lewis and Meacham spoke, attendees took turns sharing personal stories of trail use, including instances of harassment on the trail. Some speakers were furious, while others expressed bewilderment at how the situation had dragged on for so long. Indeed, the lack of visible progress had begun to invite comparisons with the 2014 Bundy standoff in Nevada and 2016 occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon, in which armed–and, some have pointed out, conspicuously white–militants had been treated with apparent indifference by government authorities after seizing and occupying public parklands. Meacham insisted that the MOA was, in fact, providing as much help as it could.

Toward the end of the meeting, a man rose to speak. He identified himself as a longtime former coworker and friend of Pugh. He said he had spoken with Pugh shortly after Pugh purchased his lot. Pugh had always known about the trail and the public easement, the man said. Eliminating the easement and closing the trail had been Pugh’s plan from the beginning. He continued: “Either he feels like the law is unfair or he wants money.”

There was an audible gasp in the room. The man sat down, seemingly unaware that he had just dropped a bomb into the battle for the Stewart Trail. The room hummed with quick, whispered conversations.

At the front of the room, Friends of the Stewart Trail attorney Tom Meacham nodded. “Yes,” he said, “We’ve heard several stories of that effect.”

The Stewart Trail

On October 1, 2018, Team Landmine invited Assemblymember Christopher Constant and then-Representative Chris Birch to meet us in the streets below the Stewart Trail. We had explained the situation to our hiking partners, and both were curious to see the trail for themselves. The “Chris’s” hadn’t met before and occupied opposite sides of the political spectrum, but nothing encourages bipartisanship in Alaska like the prospect of an interesting hike.

We climbed past a line of game cameras on a side trail starting at the end of Switzerland Drive, reached the Stewart Trail, and backtracked to Pugh’s gate. On either side of the gate, Pugh had apparently built elaborate fortifications of twisted branches, sticks and plastic fencing. Neither Constant nor Birch were impressed.

After a while we turned our backs on Pugh’s gate and headed up the Stewart Trail. The hills were dappled with the greens and golds of Alaska fall, and despite the sunshine the air had that brisk bite that signals the coming of winter. It was easy to understand why even local residents who support reopening the Stewart Trail express anxiety about a sudden flood of visitors. The trail, and the state park beyond it, are beautiful.

Christopher Constant, Chris Birch, and Jeff Landfield walk the Stewart Trail, October 1, 2018.

Throughout our walk, Pugh’s cameras silently recorded us. Later, Pugh recovered the memory cards, identified each of us, and compiled his footage into a video. On April 18, 2019, Pugh called in to the Mike Porcaro show and, in his distinctive drawl, accused us by name of trespass. Pugh later repeated his accusations to the audience of an Anchorage crime town hall hosted by Lt. Governor Kevin Meyer. Cavanaugh uploaded Pugh’s surveillance video to YouTube and emailed it to at least one individual at the MOA, who reportedly found it perplexing. Strangely, the video shows one man who had not been a part of our group. He appears to be walking his dog.

Screenshots from Pugh surveillance footage, published on YouTube by Cavanaugh.

It all seemed like so much work. Patrolling the trail. Hiding cameras. Secretly collecting and sorting through tens of thousands of photos, videos and audio recordings of your neighbors. The emails, the blog posts, the relentless confrontations.

In a call earlier that year, local resident Christine Sitbon told the Landmine she had walked and skied on the Stewart Trail since 1994. She’d stopped using the Stewart Trail after Pugh erected his gate because she found the situation depressing.

“You walk down the trail and there’s this camper and posted signs, to me it feels like the dog in the manger. ‘I’ve got this now and all of a sudden nobody can use or appreciate it because it’s mine all mine.’ It’s really sad.

Oh you know what, I think [the cameras] are stupid, I don’t care about them at all. I think they’re a waste of money, and if he wants to spend all of his time looking at people coming and going I feel sorry for him. If it were me and I had bought that property in the first place I would have done a little more research. And if I saw that it was a well-established trail, which it was, I probably would not have bought it planning on not letting other people use it. I think it’s cruel and thoughtless. I don’t know what grand designs they had when they purchased the property but it’s really too bad, because I think they’ve turned the whole neighborhood against them, needlessly. That’s my final thought.”

The battle for the Stewart Trail has aroused powerful emotions: anger, annoyance, fear, frustration. But it was hard not to have some reluctant sympathy for Pugh and Cavanaugh too. Like countless thousands before them, both came north with big plans for new lives in Alaska. Pugh, it seemed, dreamed of finding real estate riches in the steep slopes of upper Potter Valley. And Cavanaugh’s blog reflects a genuine, if somewhat cheechako, appreciation for the wildness of his adopted home.

But Pugh and Cavanaugh weren’t homesteaders or pioneers. And they didn’t walk into the quasi-lawless Anchorage of decades past, where it may have been possible to seize longstanding public access with threats and gates. Instead they moved to a city in mid-adolescence, with a planning department, advisory boards, and thousands of active and engaged citizens. A city where most of the homesteader roads had long since been paved over, the trails had been blazed a generation ago, and the mountains already belonged to everyone.

Lock on Frank Pugh’s gate, photographed December 2, 2019.

Stewart Trail series

This article is part of the Alaska Landmine's coverage of the Stewart Trail access controversy

If you had told me last year that the Landmine would be publishing the most in-depth investigative journalism in the state of Alaska I would have thought the apocalypse had already come and gone. Whatever you guys are doing, keep doing it.

Great article on an important issue in Anchorage. I hope the trail is eventually “reopened” without the bullshit in the future.

Fascinating read and quite thorough. I’ll just make a brief comment that if you have to pay to be a part of a society that declares you have high intelligence, well you ain’t that smart to begin with.

There’s smart, sharp, intelligent, thoughtful and slow but in time knowing and wise, and know it all’s who have trouble every day of their lives putting the correct shoe on the correct foot.

Anyhow well said above, “I’ll just make a brief comment that if you have to pay to be a part of a society that declares you have high intelligence, well you ain’t that smart to begin with.”

Reply

This piece tries to set the impression that landowners in the vicinity of Stewart Trail endorse open access. Nothing could be further from that insinuation. Before and after Frank Pugh bought his property people accessing Stewart Trail disregarded the property rights of nearby neighbors. Parking is a huge problem. Before Pugh bought the property nighttime parties and litter were a constant problem. The piece also neglects to acknowledge that there are multiple access points to Chugach State Park other than Stewart Trail.

okay boomer

Frank – I don’t know how long you’ve been in the area, or where you live, but my folks homesteaded the 1/4 section north of Earl Hutchins old homestead (Doc Schoff’s place, to us kids – as he bought it from Earl). Our old homestead is now Mountainside Village, which we developed and lived on until a dozen years ago. I grew up in the house adjacent to the 120 acre Hutchins/Schoff piece, and later built a home above it on Big Mountain Drive and that trail was always open. No one asked Stewarts or anyone else for permission –… Read more »

Dan Rogers is an authoritative voice on this whole case. I knew his parents Dan and Helen starting in 1982 when we bought a lot in Mountainside Village and built a house. We were the 4th house up there at the time. Dan Sr. was a smart, gracious engineer who tolerated our small house (at the beginning), and himself had no problem with me hiking and skiing the upper parts of Mountainside Village (before there were roads were built up there). As for Ivan and Oro Stewart, as Dan (Jr) says, they had no problem with us using the Stewart… Read more »

This isn’t a real person lol

At least two of the Board Members of Friends of Stewart Trail live within 400 yards of the Stewart Trail and there are several other neighbors who have submitted notarized affidavits and made monetary contributions to the cause. The nearest access points to Chugach State Park are the micro-Trailhead at Honey Bear, the end of Canyon Road, and Turnagain Arm Trail across from the Potter Section House. None of those access points offer the same kind of grade perfect for young children and people of limited mobility with unfettered views up and down valley. With the closure of the Stewart… Read more »

“…he explains in one post, “no matter how our personalities line up or compliment [sic] each other.””

Sic burn, Paxson!

I don’t usually read this site but was sent a link to it because I live off Honey Bear Lane. Honestly. I don’t know why you put us in your article. We are not even remotely involved in the Stewart controversy. Was there a word count requirement on the article submission? I feel compelled to set the record straight. We have an active and vibrant trailhead in our neighborhood. This past summer and after working with traffic enforcement on improvements, we had one of the best summers yet for co-existence between residents and hikers. Less illegal parking and less tickets… Read more »

sean, as article explains your neighborhood has such problems with trash, parking, etc because y’all VOTED to stay out of the parks area so you could keep dodging that parks tax. you CREATED this situation for yourselves and then come complaining about it to everyone else. how about your hoa removes the rocks that y’all put in snow bear (a PUBLIC street) so people can park on it? come on, admit it,you know who did that.

The assumption that that park tax in some way fixes the problems of trash and parking is a little presumptuous. Secondly, to say that the homeowners are somehow at fault for “creating the situation” of littering and illegal parking is asinine. You are smart enough to be a CPA? I will make sure to choose someone smarter for my bookkeeping.

eric, please re-read the quotes from weddleton, your assembly person. he spells it out pretty clearly: the city can’t you with litter, parking, etc. because upper hillside voters ACTIVELY VOTED to keep it that way. want help with those problems (which exist everywhere in every city)? join the parks and rec service area! beyond that, it is just ridiculous that ppl on the upper hillside are dodging the park taxes anyway. residents in mountain view, muldoon, downtown, midtown, etc. ALL pay this tax. dodging it, even if you can do so legally, is embarrassing. what, y’all expect us to believe… Read more »

Creep defends creepier creeps.

I personally have tried to access the Honey Bear Trailhead parking area in late winter/early spring and been unable to because the cul de sac was blocked with plowed snow. Had the snow been pushed up against the “No Parking” signs, I would not have had a problem. There is no way fire department equipment could have accessed, much less turned around in, the space. I have photos. I can tell you that not everyone who wanted to hike from Honey Bear was able to do so without stress. Even waiting until 2100 hours on weeknights was sometimes insufficiently late… Read more »

Most people I know avoid starting hikes at the Honey Bear parking lot these days. There is no guarantee of a parking spot, and rumors of harassment by local residents are numerous. Nobody wants crime in their neighborhood, but it persists across this city nonetheless, regardless of the stringency of parking rules. Sean’s citation of the “sixth car” problem is laughable, about as much so as a five car access point (that’s 1 spot per 60,000 Anchorage residents) to a massive public use area. This is a shame, because the location provides access to a beautiful section of ridgeline up… Read more »

Snow Bear Lane is a public access road and illegally blocked.

commented on the wrong one on accident… but registered as a Republican huh? Never would have guessed

I really appreciate Sean’s well-thought-out and expressed comments, and can’t disagree with anything he said. His points are well taken and he is just the kind of neighbor one wants to have living adjacent to a park access point. Illegal and/or disgusting behavior is always a potential problem where roads dead end at a park boundary. The challenge is to figure out how to curb the bad behavior of those people who are simply looking for an out-of-public-view spot to engage in such activities, without restricting access to the park by legitimate users who simply want to be able to… Read more »

I’m sympathetic about the crime, but it sounds like the Honey Bear residents are engaged in their own illegal behavior (blocking off a public city street and putting illegal signage on it, even after the city told them they couldn’t!). And there are so many stories of hikers and berry pickers being harassed by residents up there. It’s a bad situation, but there’s a lot of blame to go around unfortunately. Also, the “fire truck turnaround” thing is obviously an excuse to keep hikers away. If they really cared about that fire turnaround they sure as hell wouldn’t fill it… Read more »

“One of the best summers for co-existence between residents and hikers” has come at the cost of severe restrictions on public access due to parking scarcity and harassment by nearby homeowners. Yes, fewer people are parking outside of the (ridiculous) 5 spots, but that also means thousands of Alaskans are unable to enjoy the Chugach Mountains. The idea that everyone who wanted to hike was able to do so is preposterous–those people who used to legally park there on the roadside didn’t just disappear. They were instead forced into some other hillside bottleneck, or they didn’t hike at all. A… Read more »

I disagree with Sean:

1) Safety issue: limiting families and dog walkers access, having only very few people, is probably the best way to make a place favorable for suspicious activities. Proof: your dead end problem. With more people you may unfortunately get some trash, but hopefully less needles, condoms etc….

2) 5 cars only for McHugh – this is ridiculous. This is a great hiking place. And Public Land must be accessible.

Very interesting read! Living in Bavaria I enjoyed learning about a local conflict like this in such a distant part of the world! Greetings to Alaska from a German journalist!

Yes, this kind of thing would not happen in most places in Europe where “Freedom to Roam” or “everyman’s right” is fairly prevalent. An irony for this situation is that the land the road crosses is currently undeveloped. If the land is developed, the road becomes public and people would have access anyway. Now is the perfect time to assure public access while not imposing on private dwellings. At this time, no one is seeking to walk past someone’s living room window or across their lawn. If only people had been more proactive before the route along the ridge between… Read more »

Wow. These guys just sound like two outstanding citizens of Alaska. One bought the property to make money off of a public trail & the other needs to remind us how “smart” he is. FYI, Mensa members normally don’t mention it & they definitely don’t brag about it. Scratch Alaska, this dude just sounds like an outstanding citizen of the world. My pedestrian aptitude cannot wait for this to blow up in their faces. Karma, dudes…headed your way.

I haven’t listened to the Porcaro show (and won’t), but saying that someone has committed a crime is, if untrue, slander per se. Here’s your chance LM Team: Sue Pugh for slander. His will have the burden of proving that his statement is true – that you are trespassers. When he fails (and you recovery your nominal damages and attorney fees), there will be a judicial decision that the trail constitutes a public easement.

Great article! As a resident of Anchorage who previously had not hiked these trails-I’m inspired to begin hiking them this coming season!

Under Alaska’s criminal statute, it’s legal for trappers or hunters to access “unimproved and apparently unused land” unless the land is marked with 144-square-inch signs that give information about the people who can grant access, and specify prohibitions like “No Hunting” or “No Trespassing”.

Unless I missed a point- no where in this article does Alaska Landmine mention “Private Property ownership Rights” As longtime homesteaders of Potter Heights (60+ years) We knew The homesteaders that created Stewart road (the Millers were one) none of them did it to give the “public” recreational access to their land-Period!- Private property is just that- I stand with Frank Pugh, and other Potter land owners that want their privacy preserved.

Yes, Dennis, you and other landowners including the developer of the Southpointe Subdivison, have done your best to shut down access to the ridge between Turnagain Arm and Potter Valley, which extends to the “Ruby” Peak referenced in the article. The Municipality has shown the route from sea level to McHugh on its maps for decades, yet the developer tried to tell me there were no trails in the area about a decade ago while he and I stood on the exact trail that runs along the spine of the ridge and inconveniently across several of the lots. He disingenuously… Read more »

In the end, the current land owners affected by the prescriptive easements have a wonderful opportunity to establish a positive legacy for themselves and their heirs by working nicely with the community. Or, they can let their legacy be one of ill will. It’s up to them to choose how they want to be remembered.

Thank you all of those working on this. I Am so thankful for your persistence and work! The trail was one of my favorites as well and I miss it. It makes me really angry that this has gone on so long, upstanding people in our community such as Nancy Pease has been attacked and that Pugh and Cavanaugh have been allowed to bully the public. I live by the park entrance off of Upper Huffman. I understand it is frustrating when people come up to do drugs, sell drugs or just eat lunch and throw their garbage out the… Read more »

If you are a 10 or more year user of the Stewart Trail, please consider submitting an affidavit describing your experience. Send an email to friendsofthestewarttrail@gmail.com thanks

Saddened- this is so not the Alaskan spirit. The Alaskan spirit is to allow all to enjoy the outdoors and do things for the greater good of the community, not just ones own self (that is a very American quality- the self serving, individualistic culture). My mom grew up hiking these mountains, I grew up hiking these mountains, and now my kids are growing up hiking these mountains in the Alaskan spirit where folks cheer them on and enjoy the next generation growing up in the outdoors enjoying the adventure. to many more hikes, and keeping our trailheads open and… Read more »

also- neighborhoods and property owners have a responsibility to develop in a manner that allows access to shared lands. that’s why the city originally made it apart of the development of the neighborhood to create and maintain the honey bear access in the first place- now I do believe that additional funds to expand the parking perhaps should be granted.

But now I’m just pissed off.

How does “Mattanaw” access his parcel? The maps make it appear that his only access is via Stewart Trail. Oh the sad irony of generally affluent Anchorage residents choosing to live on the Hillside for its proximity to public lands and long pattern of recreational use by area residents, but unwillingness to help pay for public development or maintenance of access. “I bought into the club and should have special privileges… but I don’t want to pay dues or let anyone else in.” And yet again, wealthy white male landowners chose a path prioritizing their greed, assertion of exclusive rights,… Read more »