A couple of months ago our column discussed the significance of oil production levels. At the time, we focused mostly on the material jump in FY22 volumes projected in the Preliminary Fall 2021 Revenue Forecast (Preliminary Fall21 Forecast) over what had been included in the Spring 2021 Revenue Forecast (Spring21 RF).

Since that time, both the updated projections included in the final Fall 2021 Revenue Sources Book (Fall22 RSB) and a couple more months of actual FY22 experience have become available. Conoco Phillips also has made announcements about some additional sources of supply it is bringing on in the remaining portion of this fiscal year.

In addition, since we started down the road of analyzing Governor Mike Dunleavy’s (R – Alaska) 10-year Plan in the last few columns, we have taken the time also to dig into the projected production profile over the same, 10-year time frame.

In this column we update and broaden our look at where oil production is headed. We start with the 10-year outlook first, and then conclude with an update on the current fiscal year.

10-Year Outlook

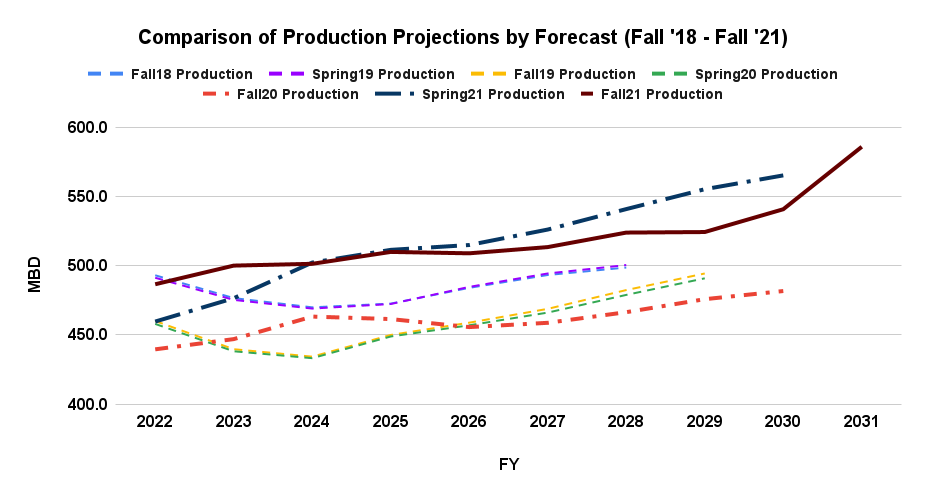

Anyone’s first reaction when looking at the Fall21 RSB production outlook is likely to be “what a difference a year makes.”

Published in the midst of COVID and with Hilcorp still getting its arms around Prudhoe, the projections contained in last year’s Fall 2020 Revenue Sources Book (Fall20 RSB) (red, lower Morse code line) were downright depressing. While the projections showed some improvement over the previous Fall 2019 projections (yellow/green, dashed) in the mid-term (2023 – 2026), both the near and longer term projections were below not only the Fall 2019 forecast, but also the previous 2018 version (purple, dashed).

The new, Fall22 RSB (maroon, solid line) tells a significantly different story. All three of the periods we look at – near (first three overlapping years), mid (next three overlapping years) and longer term (final three overlapping years) – are up significantly in the Fall21 RSB compared to the Fall 2020 forecast.

The near term (FY2022 – 2024) is up 10.3%, mid term (FY2025 – 2027) up 11.4% and the longer term (FY2028 – 2030) up 11.6%. In absolute terms, the projection for FY22, the first year common to both is up by 47 MBD (487 MBD v. 440 MBD); by FY30, the last year common to both, the increase is nearly 60 MBD (541 MBD v. 482 MBD).

The changes were first foreshadowed in both the Spring21 RF and the Preliminary Fall21 Forecast, but only at a top line level, without the field-by-field data contained in a full Fall RSB necessary for a better understanding of the factors involved. The publication of the final Fall21 RSB enables a more detailed look.

For simplicity’s sake, in charting production we regularly break North Slope volumes down into four regions – Central ANS (which largely consists of Prudhoe, its satellites and Milne Point), West ANS (which largely consists of Kuparuk, its satellites and Alpine), Offshore & Pt. Thomson (which doesn’t neatly fit elsewhere) and “Growth” (which includes projects under development, and currently is largely driven by Conoco’s Willow NPRA project and Santos’s – formerly, Oil Search – Pikka project).

We also include a solid line subtotaling “ANS minus Growth,” in order to permit an understanding of how much of the forecast separately is from already producing sources versus “Growth”.

During the 9-year overlapping period covered by both forecasts, the Fall20 RSB “ANS minus Growth” fell from a starting point (FY22) of 437 MBD to an ending point (FY30) of 330 MBD, an overall decline for the period of 107 MBD or 24%.

Nearly 80 MBD of the decline came from Central ANS (largely, Prudhoe), with the remainder coming from Offshore & Pt Thomson (12 MBD) and West ANS (largely, Kuparuk) (17 MBD). “Growth” over the period was projected at 150 MBD, leaving a net gain of 42 MBD or 10%.

The Fall21 RSB paints a much different picture over the same 9-year period, particularly with respect to the already producing fields.

“ANS minus Growth” declines only 64 MBD (13%) from the starting point (FY22) of 483 MBD to the ending point (FY30) of 419 MBD. Central ANS still leads the decline, but only at 60 MBD (v. 80 MBD in the Fall20 RSB); Offshore & Pt Thomson also shows a smaller decline (8 MBD v. 12 MBD), and led by the Kuparuk Satellites, West ANS actually shows an increase of 4 MBD (v. a decline of 17 MBD).

Moreover, largely reflecting the now, delayed start of Conoco’s Willow project, projected “Growth” over the overlapping period is actually down from the Fall20 RSB, from 150 MBD (Fall20 RSB) to 118 MBD (Fall21 RSB).

That means more than all of the nearly 60 MBD upward difference between the overall, FY30 ending point projected in the Fall21 RSB (541 MBD) versus that projected in the Fall20 RSB (482 MBD) is due to the much, much better than previously anticipated results from the already producing fields.

The fact that the upward difference is coming from already producing fields is important beyond simply the volumes it represents. Because building production from within already producing areas doesn’t require nearly the same panoply of new permits and also, largely involves scaling up existing production areas and infrastructure rather than stepping out in at least somewhat less well known areas, production from already producing fields generally is subject to less risk.

That’s not to say that “Growth” is not important to ANS production. It is; without it overall ANS production would be in decline. But based on the projections in the Fall21 RSB, maintaining efforts to slow the decline in the already producing fields ranks at least as important, if not more so in the near and mid-term, to “Growth”.

For those interested in Alaska’s longer term outlook, it will be important to continue closely to follow the discussion and likely legislative probing on the updated production forecast in the weeks and months ahead.

FY22

In our earlier, mid-November column on production levels we expressed some skepticism about the projected, 6% increase in FY22 volumes (487 MBD) over those included in the Spring21 RF (460 MBD), which itself was a significant (4.5%) increase over those included in the previous Fall20 RSB (440 MBD) .

Events since have moderated that skepticism. First, the subsequent release of the Fall21 RSB has enabled us to identify the source of the increase, at least compared to the Fall20 RSB. Effectively all of it comes from increased production levels in the Central ANS, primarily Prudhoe and its satellites, but also the GPMA/Lisburne area as well. Slight increases in some of the other areas are offset by slight decreases elsewhere.

Since completing their turnaround in July, the Central ANS areas have consistently been running at levels which appear to be on track to match the level projected in the Fall21 RSB. Even accounting for the usual shoulder month output declines, if the Central ANS stays on its current curve it should match the production levels anticipated for it in the Fall21 RSB.

And the slight increases in some areas, necessary to offset the slight decreases in others appear on track as well. Supporting that is Conoco’s December announcement of the start-up of its Greater Mooses Tooth-2 project, a West ANS project.

That does not mean we have set aside all skepticism. As our latest “Second Thursday Chart” demonstrates, overall ANS production still needs to average 507 MBD – 8% above the year to date average – through the remainder of the year to achieve the FY22 projection. But given the post-summer turnaround numbers particularly for the Central ANS area, we have growing confidence in the projected numbers.

Moreover, as the Dunleavy administration’s revenue projections and oil prices have evolved since the time of our earlier column, the importance of the FY22 volume projections has softened somewhat. The Preliminary Fall21 Forecast, current at the time of our November column, projected $2.91 billion in traditional revenues for FY22, based on an oil price of $81/bbl and volumes of 488.4 MBD. The subsequent Fall21 RSB has backed off that somewhat, projecting $2.66 billion in traditional revenues, based on an oil price of $76/bbl and volumes of 486.7 MBD.

With the current futures strip now projecting an FY22 price in the neighborhood of $80/bbl, precisely hitting the volume projection is not as important to achieving the overall budget as was the case in November. Production levels can slip a few MBD and still hit overall anticipated revenues.

As we indicated in our November column, we follow volumes closely, posting updates each Thursday on our Facebook and Twitter pages. For those interested, we will hi-lite any future material changes to the current outlook there.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Brad, would you (or someone) mind explaining what ‘MBD’ stands for, for those of us not in the know? Or is a smidge of literary courtesy too much to ask?

Thousand of barrels per day.

Oh, of course. Silly me.