This week’s column addresses three separate issues that have arisen over the past few weeks.

The first, raised in a column written in the Alaska Landmine by former Revenue Commissioner Bruce Tangeman, is whether Alaska has a large enough tax base to support the state’s current budget. The second, raised in another Landmine column written by Rebecca Logan, the CEO of the Alaska Support Industry Alliance, is whether Alaskans are receiving their “fair share” of revenues from Santos’ Pikka Project.

The final issue, raised in the course of a series of Facebook posts by Senator Rob Yundt (R – Wasilla) discussing the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD), is whether substituting tax revenues for PFD cuts, as we have suggested in previous columns, is economically prudent.

In his column, Tangeman claims “that we cannot extract enough revenue from our small working population to support this unrealistic budget behemoth.”

We’ve heard that before: it’s the same claim we often hear from others about why we can’t substitute alternative revenues for cuts in the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD). But as we explained in a previous column, “the claim is… hugely wrong. It is the Alaska version of an urban myth.”

What some don’t realize is that Alaska’s adjusted gross income has grown significantly since the early 1980s, when Alaska last had statewide taxes. Using the most recent state-level numbers published by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Alaskans had a combined $30.3 billion in adjusted gross income in calendar year 2022. Adjusting for Alaska-sourced income received by non-residents (10-20% of in-state income), which would also be subject to state tax, and further adjusting for inflation (at 2.5%) to bring it forward to 2025, results in a current combined adjusted gross income of roughly $35 billion.

Including the amount of the 2025 PFD cut, which would have been paid had other alternatives been used to cover the incremental costs of government, adds another $1.77 billion, bringing the total potential adjusted gross income to nearly $37 billion. Covering the $1.77 billion deficit entirely through an income tax rather than PFD cuts would result in an average rate as a share of adjusted gross income of less than 5%, putting it in the lower third of state income tax rates nationwide.

The potential statewide sales tax base is similarly substantial. Using the latest estimate of private-sector state GDP as a base, the same approach as former Representative Ben Carpenter’s HB 142, introduced in the 2022-23 Legislature, yields a potential tax base of roughly $60.5 billion. Covering the $1.77 billion deficit entirely on that ultra-broad base would result in a statewide sales tax rate of approximately 3%. Even if the tax base were reduced by $10 billion through exceptions and exclusions, the tax rate would still be only 3.5%, again well within the lower third of state sales tax rates nationwide.

The rates would be half those – an average income tax rate of 2.5% and a sales tax rate of only 1.5% – if, as in most states, both approaches were used to raise a share of the required revenue. Both would be among the nation’s lowest.

And the rates would be even lower if, as part of the comprehensive fiscal plan proposed by the Legislature’s 2021 Fiscal Policy Working Group, the Legislature restructured the PFD to equal 50% of the Legislature’s annual percent-of-market-value (POMV) draw and also updated the state’s current oil tax approach to meet the Constitutional standard. In short, Tangeman’s claim is just hackneyed rhetoric. It doesn’t hold up when using actual numbers.

In her column, Logan seeks to defend Alaska’s current oil tax structure, claiming she is “disappointed to see some using the Pikka Project as an example of Alaska not getting its ‘fair share’ from Alaska’s oil and gas production tax, SB21.”

But Logan’s so-called “facts” defense is full of holes. She asserts, for example, that “over the past quarter century, with the exception of the ACES years, royalties have outpaced production taxes as the state’s largest revenue stream.” But that wasn’t true in the revenue forecast included in the Department of Revenue’s (DOR) Fall 2014 Revenue Sources Book, which reflected what the administration of then-Governor Sean Parnell and others told voters to expect if they rejected the 2014 referendum on repealing SB21 (which they did).

In those, the Parnell administration predicted that production taxes would exceed royalties in seven of the ten years of the forecast period (Fiscal Year (FY) 2015-24), ultimately outstripping royalties by nearly 20% over the period.

And, Logan’s claim doesn’t hold up even in the face of lower-than-projected oil prices over the intervening decade; in FYs 2022 & 2023, for example, revenues from production taxes outstripped royalties by nearly 35%.

And even if production taxes did not outstrip royalties over the entire decade, they still made up over 40% of the combined total. That compares with reaching only 28% of the combined total over the next decade as projected in the most recent Spring 2025 Revenue Forecast, significantly lower than either in the pre-ACES or the first decade of the post-ACES periods, despite a massive (more than 40%) growth in production volumes.

Logan also claims that “large projects everywhere – Alaska, Asia, Latin America, or the North Sea – typically recover their spent development costs before paying production taxes.” That is true only to a certain extent. In a large number of instances, the producers recover their capital costs only on a ring-fenced and/or amortized basis – i.e., only from the production resulting from the investment and/or spread over a number of years.

Alaska’s system is substantially more generous to producers, permitting them to recover their costs from all production (not just that resulting from the investment) and in the year of expenditure (rather than spreading them over time). Both provisions substantially accelerate the benefits received by Alaska producers compared to those elsewhere, significantly reducing the amount of taxes paid in the early and highest production level years.

Moreover, Logan doesn’t even mention Alaska’s unique Gross Value Reduction (GVR) provision, which, layered on top of already generous cost-recovery provisions, further exacerbates the revenue shortfall. As we explained in an earlier column, borrowing from DOR’s Fall 2024 Revenue Sources Book:

The gross value reduction (GVR) allows a company to exclude 20% or 30% of the gross value for that production from the tax calculation. Qualifying production includes areas surrounding a currently producing area that may not be otherwise commercial to develop, as well as certain new oil pools. Oil that qualifies for this GVR receives a flat $5 Per-Taxable-Barrel Credit rather than the sliding scale credit available for most other North Slope production. As a further incentive, this $5 Per-Taxable-Barrel Credit can be applied to reduce tax liability below the minimum tax floor assuming that the producer does not seek to apply any sliding scale credit.

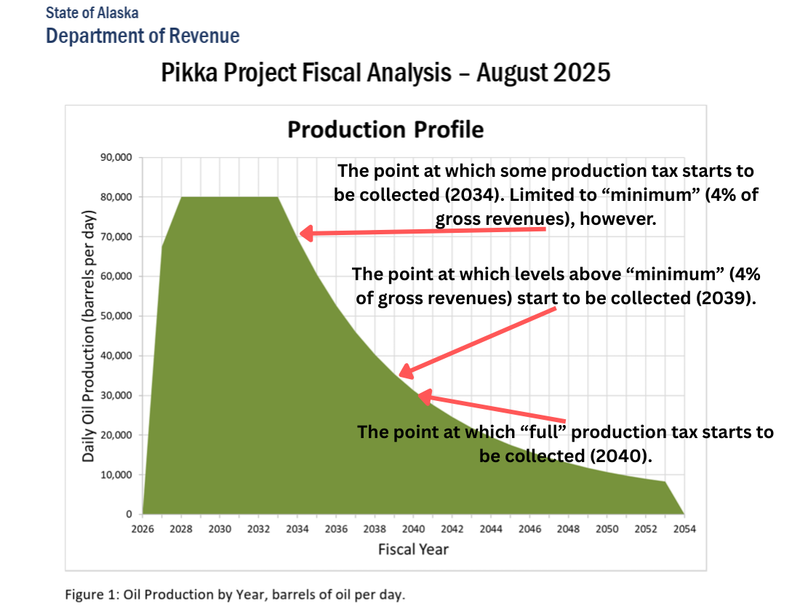

As this annotated chart from DOR’s analysis of the Pikka Project demonstrates, it is this provision – unique in the industry – that, layered on top of the others, allows Santo’s Pikka Project to reduce production taxes not only below the so-called “minimum” of 4% of gross revenues established in SB 21, but indeed to zero during the first seven – and by far the largest – years of production.

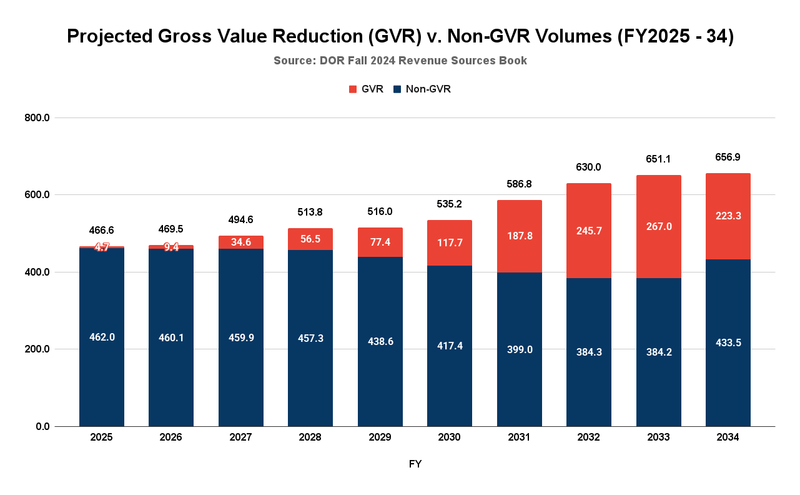

And that may just be the tip of the iceberg. Here is the level of volumes projected by DOR in its Fall 2024 Revenue Sources Book that qualify for GVR status over the next 10 years.

The volumes rapidly rise from 1% of total production in FY2025 to more than a third by FY2032 and for the remainder of the period. Given that, it’s unsurprising that annual production tax revenues plunge by over 75% over the period, from $974.6 million in FY2024 to $218.6 million in FY2032, before recovering somewhat to $429.2 million in FY2034.

Logan’s defense that Pikka will generate some revenues earlier is similarly underwhelming. Under Article 8, Section 2 of the Alaska Constitution, the standard is whether Alaskans are receiving the “maximum benefit” from the development of the resource. The fact that Alaskans are receiving some benefits doesn’t suffice.

Logan ends her column by arguing, “The Pikka Project is proof that Alaska’s fiscal system is working.” It should be rephrased to read, “The Pikka Project is proof that Alaska’s oil tax system is failing to produce the tax revenue increases the proponents of SB 21 promised as production levels rose.”

Finally, in the last segment of a three-part series on the PFD, Senator Yundt claims, “paying a larger PFD off the back of an individual income or sales tax would be a massive accounting error. The IRS considers the PFD an earned income, which is a taxable event. If we tax ourselves so we can pay ourselves then the IRS takes 20+% of it, nobody wins except the federal government.”

What Yundt overlooks is that an individual income or sales tax would apply not only to Alaskans but also to non-residents, who, unlike in every other state, are not otherwise contributing to the costs of the Alaska government. By including non-residents, substituting a state tax for PFD cuts would reduce the amount being taken from Alaska families. This year, for example, the state government withheld and diverted $1.77 billion in income through PFD cuts to cover its deficits. As we explained in a previous column, if a state tax designed to raise 15% of total receipts from non-residents had been used instead, Alaskan families would have only needed to contribute around $1.5 billion, roughly saving $265 million.

Yundt correctly says some of the amount received in PFDs would have gone to the federal government. But, as we also explained in our previous column, based on the most recent state-level data from the Internal Revenue Service, Alaskans only pay roughly 12.7% of their adjusted gross income in federal taxes. With total PFDs of $1.77 billion, that would result in only around $225 million going to the federal government.

Even after offsetting the amount saved by including non-residents in the tax base by the amount paid to the federal government, Alaskans – and, through them, the Alaskan economy – would still come out ahead by approximately $46 million.

Moreover, in addition to saving Alaskans money at the gross level, using taxes instead of PFD cuts has another significant positive impact. It would flatten the tax burden across all income brackets rather than concentrating it almost entirely on middle- and lower-income Alaska families.

As we explained in the previous column, while Alaskans would still need to contribute around $1.5 billion of the $1.77 billion burden, the share of income taken from 80% of Alaska families through taxes would be significantly lower than that taken through PFD cuts. Depending on the tax approach taken, the overall burden on Alaska families could be pushed as low as 2.7% of income, compared to the significantly higher rates resulting from using PFD cuts.

And while those in the Top 20% income bracket would pay somewhat more in taxes than the trivial amount they contribute using PFD cuts, using a proportionate (or flat) approach, they would contribute no more as a share of income than the remaining 80% of Alaska families.

As researchers from the University of Alaska – Anchorage Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) have previously explained, substituting such an approach for PFD cuts not only would reduce the adverse impact of hugely regressive PFD cuts on 80% of Alaska families, it would have beneficial effects on the overall economy as well as reduce poverty levels, and the significant cost of government programs tied to them.

We get Yundt’s point. There is a federal income tax cost to replacing PFD cuts with a state tax. But stopping there is an incomplete analysis. There are also substantial offsetting benefits that outweigh those costs.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

No new taxes while free money is distributed. You communists need to find another place to go.

“Communists”? Ridiculous slur.

Redistribution of wealth. Tax and redistribute.

Communists.

Brad Keithley is not a communist.

If he was, then everyone everywhere who has ever lived is a communist.

Mix in a smart or helpful point once in a while.

The redistribution of wealth is a clear and critical principle of communist economic ideology. Mr. Keithley is regularly promoting it in his campaign of Universal Basic Income, even to the point of taxation in order to fund it. If you prefer, I’ll retreat to an accusation of partial communist.

Better?

Nope.

Keithley is not a communist in any degree, shape, or form.

Words have meanings.

Name a single government in the history of mankind that did not effect a redistribution of wealth.

Meanwhile, enjoy your “communist” (lol):

you un-hypocritical non-communist you.

“………Name a single government in the history of mankind that did not effect a redistribution of wealth……..” Mr. Keithley isn’t a government. He’s an individual pursuing communist economic policies within government, which is why governments become communist. I do not qualify for or receive social security benefits, despite having paid into the system. I do not receive VA benefits because I am a Medicare recipient, just like all other Americans over 65 years of age, whether I like it or not, and even though I still have employer subsidized health insurance, which I paid for, and because prior to about… Read more »

Wow, even less self-aware than I expected.

Taxpayer-funded public services aren’t “communist” if they help YOUR life. Got it.

“I’m getting mine”, as you say.

By your own definition, you’re a communist.

As is everyone.

Onward, comrade!

“……..Taxpayer-funded public services aren’t “communist” if they help YOUR life. Got it……..” Obviously not. And to prove it, you resort to the sophomoric retorts that we’ve come to expect from you. Taxpayer funded services and infrastructure include government in nature (GIN) activities like police, military, roads, etc, unless you’d approve me forming my own army. I already own my own private road, and it receives no public maintenance or service. I think I’d like an army, thanks. No tanks, thanks, but some crew served weapons might be nice. I’m sure you’ll approve, no? No, “everyone” is not a communist, even… Read more »

For your elementary education, Comrade:

https://youtu.be/dE34-dovZ94?si=vW0j9UKR1pKLpfXn

(They left out Democratic Socialism)

So, I get up everyday and go to work whether I want to or not, and you’re advocating that I get punished by getting to pay tax on what I’m earning. We have many people who don’t work often due to where they chose to live, homeless or those who live off of welfare benefits. Then those people who don’t or won’t work get PFD’s. No thanks.

It’s not “punishment” to contribute to this society. It’s a privilege.

Where on Earth in the history of all humankind is/was there a civilization you’d prefer to today’s Alaska that levies/levied no mandatory taxes?

One place, one time.

Where is/was it?

FigmentOfYourImaginationIstan?

“………Alaska that levies/levied no mandatory taxes?……….”

Ummmmmm……….have you read this column? The subject of the column is Mr. Keithley again pushing taxes. I assume, since he’s using the word “tax” it’s going to be mandatory.

There are 8 other states that do not have a state income tax.

Yes. For instance Texas has no state income tax.

Instead, Texas’ governments levy (or in your word, “punish”) their landowners with one of the highest average property tax schemes in the country.

The average Texas homeowner pays an effective property tax rate of 1.58% per year, seventh highest in the nation.

A California property owner pays less than half that, just 0.71%, which is 35th in the nation.

Not sure why you only care about income tax, but there you go.

rocketmortgageDOTcom/learn/property-taxes-by-state

Well, I pay property taxes. I pay what’s required. I also pay the alcohol tax to fund mostly the homeless, I also pay the muni gas tax that a pervious administration passed with no public vote, again mostly for the homeless. It isn’t getting any better in spite of taxing working people. The difference between those taxes 2 of those taxes is I can choose if I want to pay those taxes on what I buy. An income tax, I don’t have the voice whether to buy something or not. Therefore it’s a punishment to be required to pay that.… Read more »

“…….. to fund mostly the homeless……..” This is the lie used by the political types to justify the need for the tax, but the tax proceeds are just like any other income they receive. It all goes in the Big Pot to be distributed as political pressure dictates. What I want kept in open focus is the crisis with the balance sheet on the expenditure side being used as political justification for a new or renewed tax (either income, sales, or both) while the largest single expenditure (the PFD), which provides nothing more than a retail bonanza for individuals and the… Read more »

Oh, I agree. That’s why i said possibly. It’s nuts to hand out free money and then expect working people to be taxed so some families can get a $15,000 ( just an example) chunk of money. I’ve always said that the dividend is a gift, it never was guaranteed, dependable income.