Often we hear some claim that Alaska doesn’t have personal state taxes.

That’s wrong. As former Governor Jay Hammond explained in his seminal book on Alaska fiscal policy, Diapering the Devil:

Reducing [Permanent Fund] dividends to pay for government services would impose what is, in essence, a reversibly graduated “head tax” on all and only Alaskans. The poor would pay a larger percentage of their “income” in taxes than would the rich; transient pipeline workers, commercial fishermen and construction workers would get off scot[]–free.

Taking a slightly different path, former state economist Ed King recently reached the same conclusion (“… changing the rules of the game so that the distribution gets smaller is, in fact, a tax. So, the debate is really about which type of tax to implement.”)

Even those who initially don’t view reductions in the statutory Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD cuts) as a tax nevertheless concede they are a reduction in personal income to fund government. If distributed as part of the PFD in accordance with even what the Legislature’s Legislative Finance Division (“LegFin’) admits is current law, the amount would become part of household income. By diverting a portion instead to government, household income is reduced.

Reducing and diverting personal income to pay for government is the very definition of a personal tax (Investopedia: “Taxes are mandatory contributions levied on individuals or corporations by a government entity—whether local, regional, or national.”)

More importantly, not only are they taxes (or diversions, if you prefer), they are the very worst kind, both from the standpoint of the overall Alaska economy and Alaska families.

After analyzing the impact of various revenue (tax) alternatives as part of a 2016 study for the Walker administration, researchers from the University of Alaska-Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) concluded “[t]he impact of the PFD cut falls almost exclusively on residents, and it is highly regressive, so it has the largest adverse impact on the economy per dollar of revenues raised.”

The same is true of the impact of PFD cuts on Alaska families. After analyzing the impact of a number of revenue (tax) options in its 2017 study for the Legislature – including PFD cuts, a progressive income tax, sales tax, payroll tax and a combined payroll and investment tax – the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) concluded “[c]uts to the PFD payout are the most regressive option examined in this report,” taking more from 80% of Alaska families than any of the alternatives.

Despite being the worst option from both an economy and personal perspective, the state nonetheless has been using reductions in the PFD to help fund government since 2016. As we calculated in a previous column, over that time period PFD cuts – regressive taxes on Alaska families – have averaged a little over $900 million per year.

Using the “rule of thumb” we discussed in last week’s column included in LegFin’s recent Overview of the Governor’s (FY24] Request, that’s equal to about a 3% overall average tax rate on the adjusted gross income (AGI) of Alaska families.

But that doesn’t tell nearly the whole story.

First, the actual tax rate on Alaska families using PFD cuts is higher than that calculated using LegFin’s rule of thumb. The 3% calculated by LegFin is based on using a flat rate income tax. Such a tax would apply to both residents and non-residents. PFD cuts do not, however, which requires Alaskans to contribute even more to make up the difference otherwise contributed by non-residents using other tax approaches.

In its 2016 study, ISER estimated that by using other approaches, non-residents would contribute somewhere between 7 and 11% of the total revenue produced by the tax. Using the lower number, that means by using PFD cuts Alaskan families effectively are being required to contribute roughly $60 million (about $100/PFD) more than they would under other tax approaches to make up the difference, resulting in an overall average tax rate using PFD cuts of more like 3.2%.

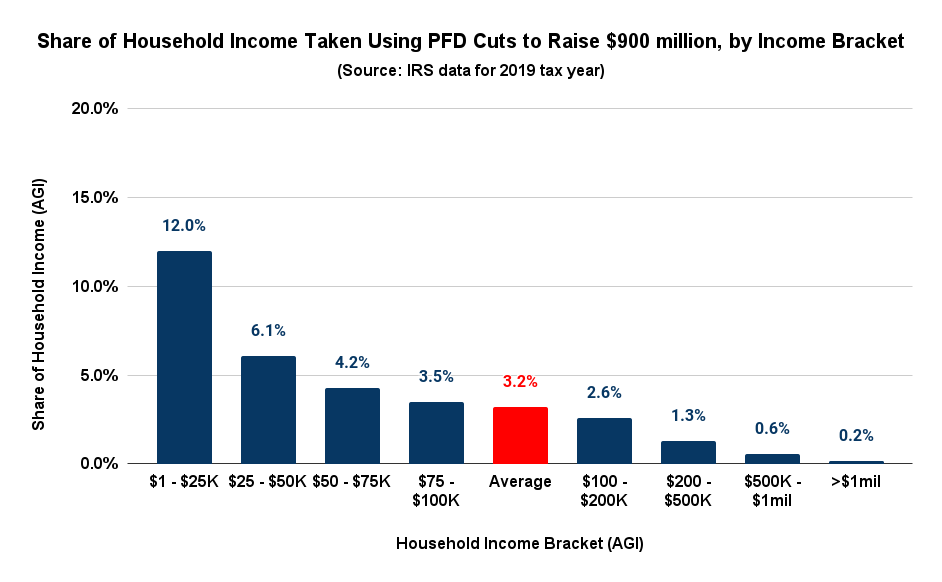

Second, that’s the average overall tax rate. Because of their highly regressive impact, the effective tax rates by income bracket from using PFD cuts vary significantly from the average. Using the same state level Internal Revenue Service (IRS) data we have in previous columns, here’s the actual impact broken down by income bracket.

One can understand why those in the upper income brackets, particularly those with adjusted gross income above $200,000 per year, think Alaska doesn’t have personal state taxes. The impact is barely noticeable to them.

But for the 75% of Alaska households looking up from the middle and lower income brackets the effect is quite different. As income levels decline, the impact of the tax becomes increasingly significant.

And some this session are pushing to make the burden even higher.

In recently discussing his bill to increase the base student allocation (BSA) by $1,250, Representative Dan Ortiz (I – Ketchikan) said the proposal “would carry a $321.5 million price tag for the state,” all of which would come from increased PFD cuts (taxes).

Using LegFin’s rule of thumb, adjusted for imposing the burden only on Alaska families by using PFD cuts, that would increase overall average tax rates by roughly an additional 1.1%.

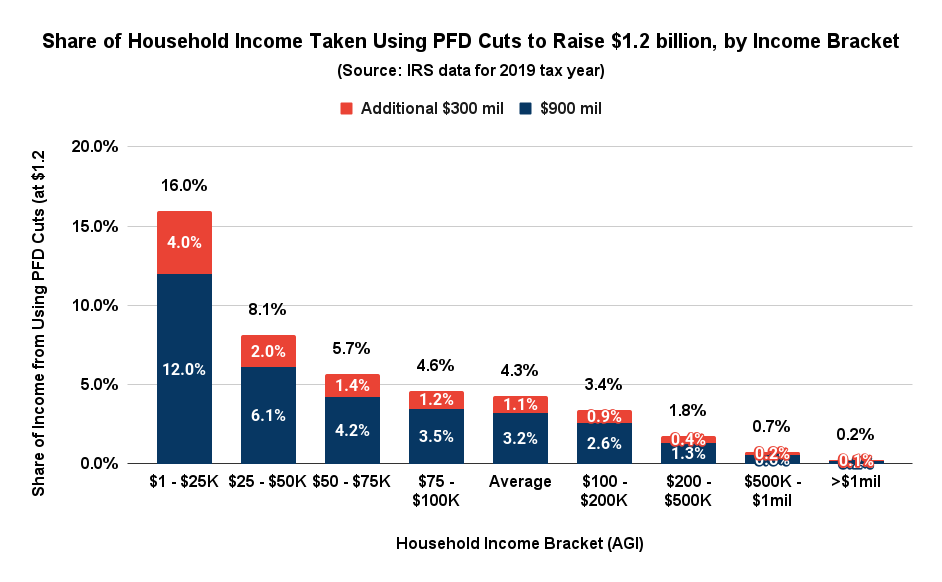

The impact from adding that to the already $900 million in funding provided through PFD cuts would make the individual rates by income bracket even more regressive. Here’s the distribution of the two combined, again broken down by income bracket:

While the average overall rate is 4.3%, those with $25,000 or less in income, what the IRS data indicate essentially is the lower quartile of Alaska households, would contribute 16% of their household income. At that level, that’s not only far higher than the tax rates imposed on their peers in other states, it’s higher than the highest marginal state tax rate in the nation regardless of income level, California’s 12.3% marginal tax rate on household income above $1.354 million (married, filing jointly).

Even those with incomes between $25,000 and $50,000, essentially lower middle income Alaska households, would contribute 8.1% of their household income, and those with incomes between $50,000 and $100,000, essentially upper middle income Alaska households, would contribute between 4.6 and 5.7% of theirs. According to ITEP’s most recent, national “Who Pays” study, both are significantly higher than the tax rates assessed their peers in other states.

On the other hand, those in the top 25% – those with incomes of $100,000 and up – would contribute decreasing amounts, ranging from 0.2% for those with greater than $1 million in income, to 3.4% for those with income between $100,000 and $200,000.

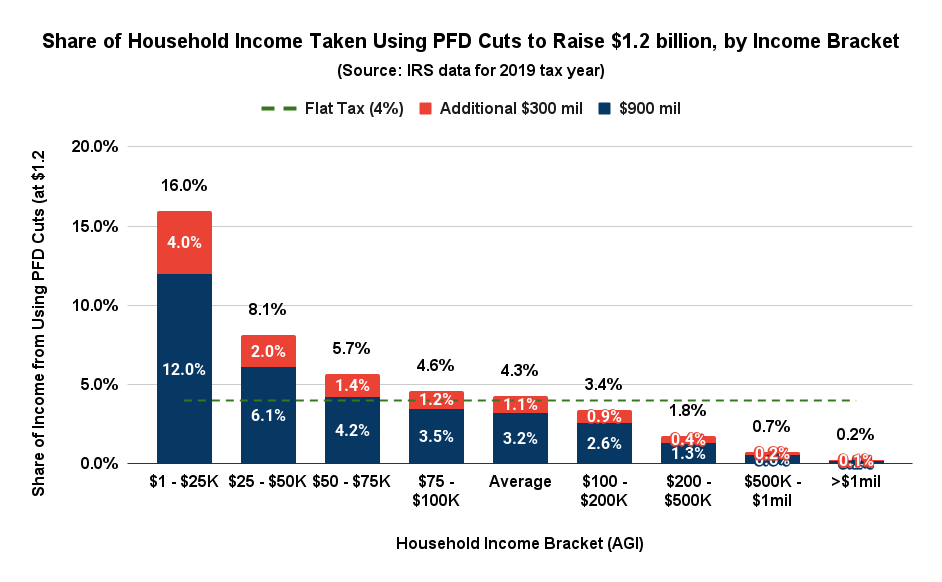

Because it would reach income received by non-residents from Alaska sources, not only would substituting the flat tax used to develop LegFin’s rule of thumb (the green dashed line in the chart below) result in a lower tax rate for Alaskans overall – 4.0% v. the 4.3% resulting from relying solely on PFD cuts – it would balance the burden equally across all Alaska families.

While those in the top quartile would contribute more than using PFD cuts, they would contribute no more as a share of income toward the costs of government than any other Alaska family and, indeed, would still be called upon to contribute materially less as a share of income than the remaining 75% of Alaska families do using PFD cuts.

Article 1, Section 1 of the Alaska Constitution provides that “all persons have corresponding obligations to the people and to the State.” It doesn’t say that middle and lower income Alaska families have more obligations than the wealthy.

Some like to skirt the issue of whether PFD cuts are taxes by saying the word “tax” isn’t used in the name. But not all taxes are called taxes. Tariffs, for example, are “a tax imposed by one country on the goods and services imported from another country to influence it, raise revenues, or protect competitive advantages.” They aren’t called a “tax,” but they are. Indeed, up until 1913, they were the largest source of tax revenue to the federal government.

As ITEP’s 2017 report recognizes, “Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) is unique among the states.” It’s unique as a personal income source (although it doesn’t use the word “income”); cuts to that personal income stream are also unique as a state tax source.

We get why, from a political perspective, some want to avoid treating PFD cuts as what they are – a personal state tax. Admitting that would trigger both deeper analysis, such as the distributional and economic impacts we discuss above, and political pushback.

Sort of like avoiding saying the name in the 1980’s classic movie Beetlejuice, those who want to avoid those effects – on both the right and the left – are hopeful that if you ignore saying the name “tax” no one will think of the cuts in those terms.

But PFD cuts are personal state taxes. They divert personal income to help fund government.

If Representative Ortiz and others believe that’s what Alaska needs, there are MUCH better ways to raise the necessary funding from both an economic and household perspective. They should propose adopting one of the less adverse and less regressive alternatives instead of continuing down the road that has the “largest adverse impact” on the state economy, and is the “most regressive option” on personal income.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Do the columns take into account families that may have multiple PFDs within that income bracket (i.e., families with kids)? If not, it seems the income share taken would be even higher for this subset of people.

Yes, we do take that into account.

BK is full of shit, as usual.

Will you please be a little more specific? If you’re part of the upper 20% and believe that your proportionately jumbo, PF-funded freebies are therefore sacrosanct, rest assured that you’re not alone. Just lay it out there on the table so we can understand where you’re coming from.

I agree with Brad’s point that we should have a progressive income tax in Alaska.

In your analysis, you have ignored the redistributive effects of increasing the base student allowance (BSA). As you have repeatedly argued, government expenditures for the PFD transfer payment are a form of income. Following this logic, would not government education spending per student be a form of income received by school districts on behalf of students and their families? A flat $1000 or $1,200 increase in BSA would increase the total state education allowance to a poor district __by a greater percentage__ than to a rich district. This is a progressive reallocation of transfer “income” received by districts from the… Read more »

Hammond didn’t consider the PFD a transfer payment. He – and the statute – treat it as a pass through of, as Ed King puts it in his piece cited in the column, trust income with government’s only role intended to be that of the trustee. The PFD isn’t “redistributive;” it’s the initial distribution of commonly owned wealth. It’s the step of subsequently diverting a portion to government and using it instead to cover the tax obligation of those in the top 20% that’s the “redistributive” step, and in that case its redistributing the money from middle & lower income… Read more »

Yes, I have read the same quotes from Hammond and King multiple times in your articles. I have also read the 2016 ruling of the Alaska Supreme Court in Wielechowski v Alaska that the legislature’s use of Permanent Fund income is subject to normal appropriation and veto budgetary processes.

That doesn’t make it a transfer payment (the Supreme Court didn’t strike down the statutory source and purpose). It merely makes it a flow through subject to legislative redirection.

This is how the people in charge want things to be. They have a libertarian fantasy ideal that suffers the least adverse effect from diminishing pfd. Taxes are theft, they are where they are because they are exceptional or chosen by God, and the poor’s are not worth consideration. How many came here to pay no taxes, in the sense that they don’t fill out a form and write a check? Michigan Militia guys, AIP guys, religion entrepreneurs, McKinley Capital, oil company people.

This state will be a territory again before these types bring back the pre Hammond income tax.

Hammond also made it very clear that the State Income tax should never have been rescinded.

If the State hadn’t, and instead, taxed people progressively, including a tax on the PFD, in such a way and amount as to provide an excellent government with a world class education system…would that be bad? I don’t think so.

The PFD has ultimately been a plague on this State, attracting this kind of entitlement thinking.

Pushing a tax to cure government overspending is like showing up to a house with a couple buckets full of: gasoline

#House fire