Some seem to be attempting to set up this next legislative session as a battle between the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) and oil taxes: “there will be room to pay a ‘significant’ PFD if oil taxes are increased.”

But that’s a false choice. The need for additional revenues isn’t driven by the PFD, it’s driven by unrestricted general fund (UGF) spending levels. And, significantly, the supposed choice (intentionally) leaves out an entire segment of the Alaska economy: the top 20%.

At its core the effort is a transparent attempt at political redirection. Rather than focus attention this coming session – as it should be – on the need for additional revenues to pay for UGF spending levels and how to raise them, the effort is an attempt to recast the need for additional revenues as one to cover the PFD, and to identify the only source of that as increased oil taxes.

That is designed to do two things. First, to redirect anger at lower PFD levels away from the Legislature. Didn’t get the PFD you want? Blame the oil companies for resisting the increase.

Second, to set a trap for Governor Mike Dunleavy (R – Alaska) if the Legislature passes an oil tax increase, but then he, as would be inclined to do, vetoes it. Didn’t get the PFD you want? Blame Dunleavy for vetoing the oil tax bill.

The approach also has the benefit to its advocates of providing cover for a fiscal sleight-of-hand. While public (and, potentially, media) attention is focused on an alleged battle between the PFD and the oil companies, the Legislature quietly diverts the portion of the Permanent Fund earnings stream (PF earnings) statutorily designated for the PFD instead to support current and increased UGF spending.

In short, the approach is a classic, Karl Rove-esque, political misdirection, designed to enable the Legislature to avoid a public debate about whether and how to raise the additional revenues necessary to support current and increased spending levels. By ignoring the PFD’s statutory call on PF earnings and diverting them instead to support UGF spending, abracadabra the revenues are already there. It’s the PFD that’s short.

The problem with the approach is that it’s built on a lie.

As we’ve explained in previous columns, by statute the PFD doesn’t need any more funding; it’s already fully funded from the PF earnings. Yes, under the Supreme Court’s Wielechowski decision, in any given year during the appropriations process the Legislature can divert (tax) all or any portion of those funds to support government spending levels, leaving funding for the PFD short, but the cause of that chain of events is a shortage of funding elsewhere for UGF spending, not for the PFD.

This column isn’t to take issue with current – or even increased – government spending levels. If the Legislature concludes – and Governor Dunleavy agrees – that increased spending levels are required, then so be it.

Instead, this column is focused on how to pay for – and more specifically, who pays for – those spending levels.

Presumably, the Legislature adopts – and the governor signs – overall spending levels they believe are in the best interests of all Alaska families. It follows as a result that, to the extent contributions from individual Alaska families are required to pay for them, that overall funding should also come from all Alaska families, equitably.

As we’ve explained in (as some will be quick to point out, numerous) previous columns, diverting all or a portion of the PFD (the PFD tax) to pay for UGF spending isn’t that – equitable. Instead, using PFD cuts are the most regressive – tilted against middle & lower income (working) families – of all of the various funding measures currently used anywhere in the United States.

As former Governor Jay Hammond said in Diapering the Devil, PFD cuts are “a reversibly graduated ‘head tax’ on all and only Alaskans.” To find a corollary elsewhere, it’s necessary to reach back to the old “poll” or “head” taxes used in the 19th Century and before.

Except PFD cuts are even worse. At least in the United States, poll taxes were focused on adults of voting age. PFD cuts tax children also.

As we’ve discussed in previous columns, and will again briefly below, there are much more equitable ways to raise any needed revenues.

This column also isn’t to take issue with increasing oil taxes. As we’ve explained in a prior column, we believe previous legislatures and the governor have left “money on the table” in terms of oil taxes that instead should have gone to the state.

But increased oil taxes aren’t enough to solve the problem.

As regular readers are aware, each Friday we publish what we have labeled our “Goldilocks charts,” which analyze the fiscal outlook for the period covered by the Dunleavy administration’s most recent 10-year plan based on current oil futures prices, the most recent earnings outlook from the Permanent Fund Corporation and our most recent look at baseline spending levels, adjusted for the market outlook for inflation.

The Friday charts then look at that baseline through three lenses related to the PFD – using the current law (statutory) approach, using percent of market value (POMV) 50/50, the Dunleavy administration’s preferred approach, and using POMV 25/75, the approach pushed by some in last session’s Legislature.

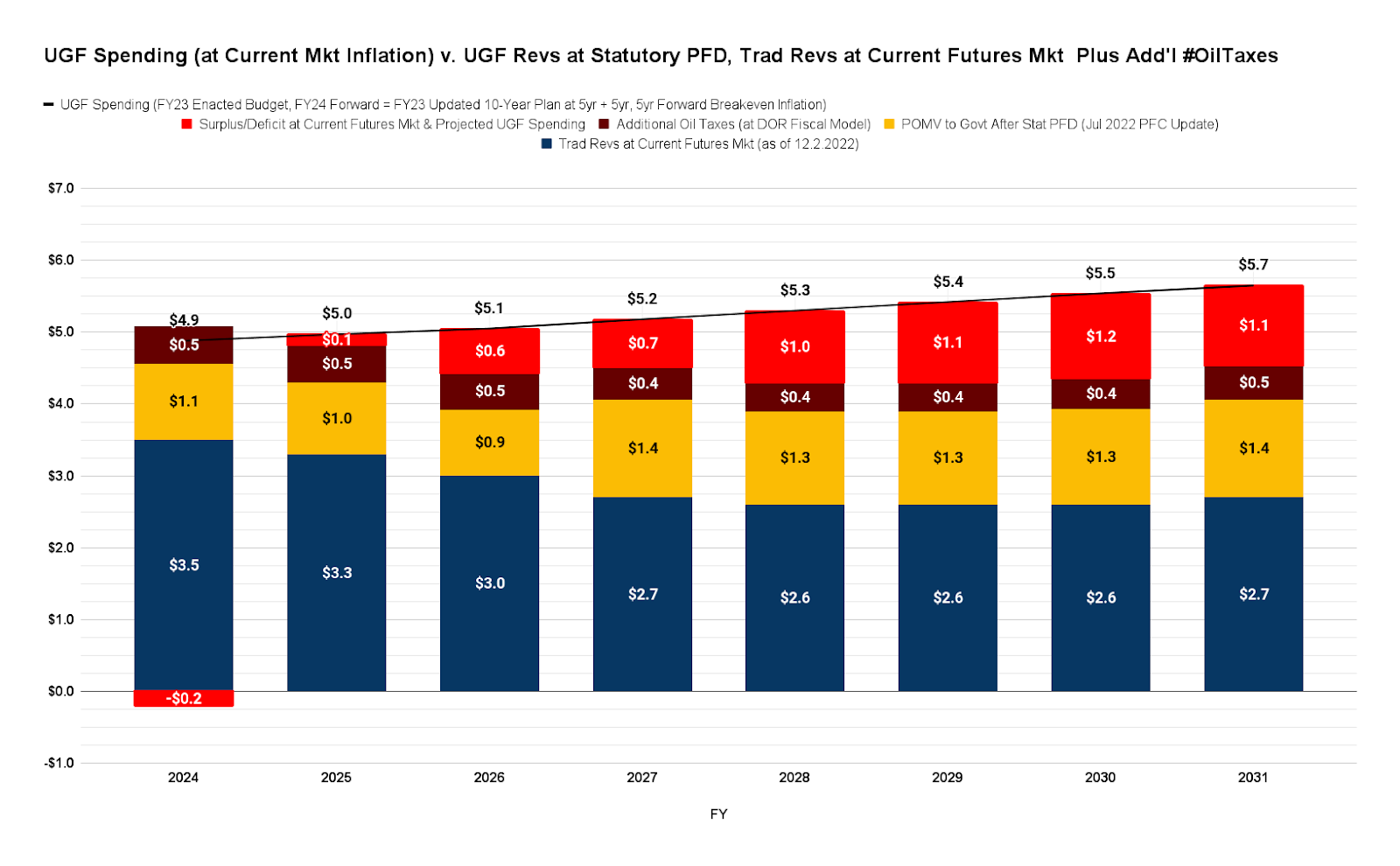

Here’s the most recent outlook using the current law (statutory PFD) approach from FY24, the fiscal year on which the Legislature will be focused this coming session, forward. The location of the red bar indicates whether, using the current law (statutory) PFD, the budget is in surplus (red below) or in deficit (red above). The chart shows that, even at current baseline spending levels (before any increase to K-12 or for any other purposes), the budget is in deficit in FY24 and remains that way going forward.

How would increasing oil taxes affect that?

Consistent with our earlier columns on oil taxes, to estimate we have used the information contained in the Department of Revenue’s (DOR) most recent, publicly available Fiscal Model, dated April 22, 2022 (DOR Fiscal Model). In that Model, DOR includes two options related to oil taxes. The first is, essentially, to close the Hilcorp Loophole we discussed in our previous column; the second is to “Reduce Current $8.00 per Barrel Tax Credit by $3.00.”

Here is the result using the revenues produced by those changes (at the projected oil price levels used in the most recent Goldilocks charts). The additional oil tax revenue revenues are in brown.

Combined, the two changes produce on average over the eight-year period roughly $460 million per year in additional revenue. While those changes (barely) close the current law deficit in FY24, even with the changes substantial and growing deficits reappear in FY25 and after.

And that assumes baseline spending, adjusted for current financial market expectations for inflation. If spending increases this session to accommodate growth in K-12 and other areas, increasing oil taxes by the projected amounts won’t be enough even to balance the budget in FY24.

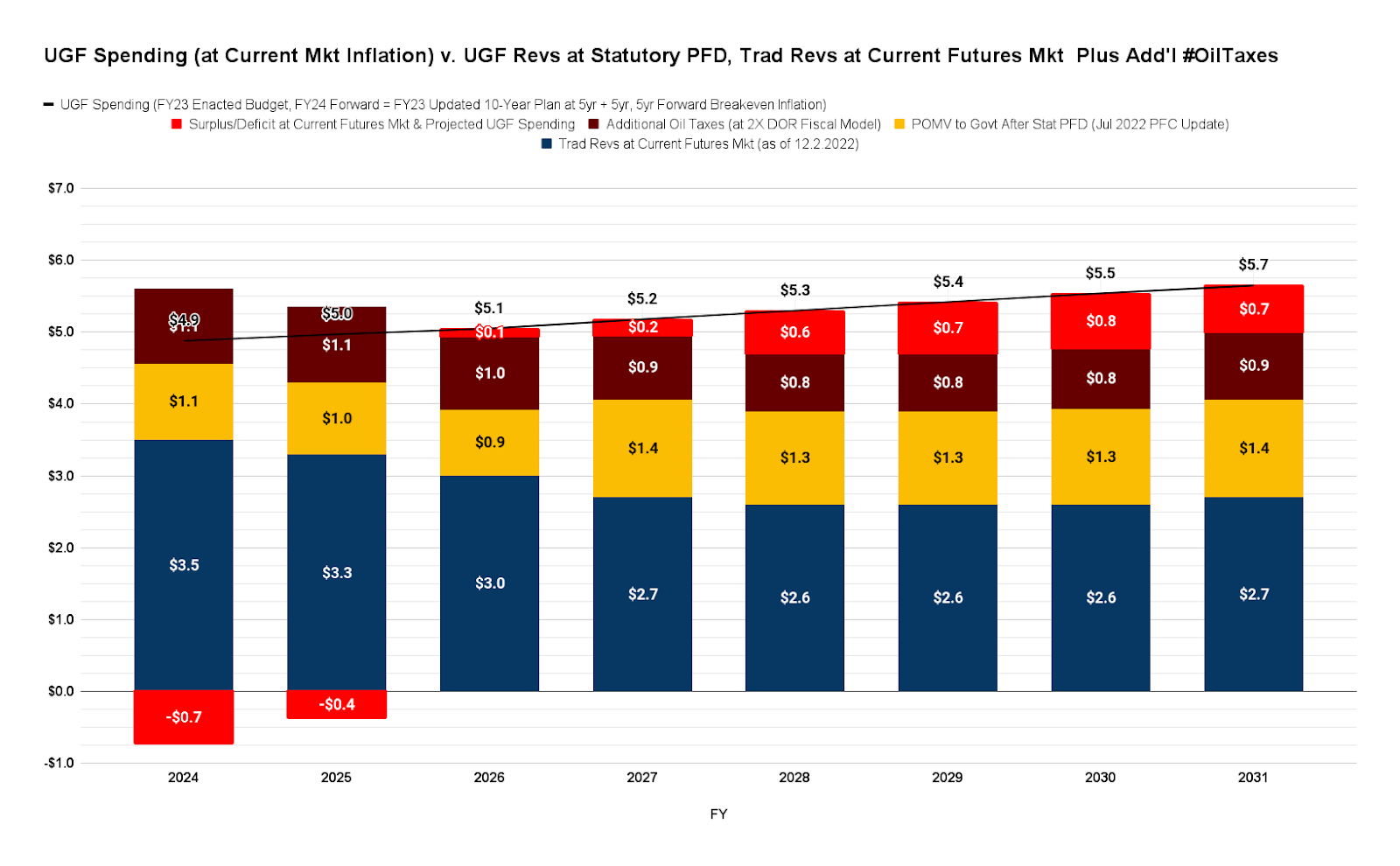

Of course, some will argue that the way to solve the continuing shortfall is simply to increase oil taxes even further. But as we explained in our previous column, once oil taxes reach a certain point – what analysts refer to as the “revenue maximizing point” – further increases become self-defeating, resulting in lower revenues over time as a result of reduced investment and with that, production.

But even assuming oil tax increases could be doubled from the levels projected in DOR’s Fiscal Model without significant reductions in investment, and thus, production levels, that still would do no more than offset likely spending increases in FY24 and, possibly, FY25. Beyond that deficits once again would reappear and grow thereafter.

The point is, even assuming oil taxes are increased all the way to the revenue maximizing point, revenues still will not be sufficient to cover likely deficit levels even in the short term, much less the intermediate and longer term.

At current and projected spending levels, Alaska families will also have to contribute some in order to cover the costs of government.

The question is how, and which Alaska families will be called on to contribute. Here’s where the top 20% come in.

As we’ve explained in previous columns, by using PFD cuts the burden of funding UGF spending is being shifted almost entirely to middle and lower income – what most label, working – Alaska families. The top 20% bears a trivial share.

By stating the issue as PFD cuts versus oil taxes, the top 20% are attempting to keep their contribution at the same, trivial level, regardless. If increased oil taxes are sufficient to cover the deficits, the top 20% won’t have to contribute. If oil taxes aren’t sufficient to cover the deficits, the PFD is cut instead. Again, the top 20% won’t have to contribute. It’s their version of “heads I win, tails you lose.”

That’s not equitable.

If, going forward, Alaska families have to contribute some in order to cover the costs of government, then all Alaska families should be called on to contribute equitably. The top 20% shouldn’t be able to dodge paying an equitable share. It’s their government also.

We discuss the ways to do that – and the impact on Alaska families of each – extensively in this previous column: “It’s THE most important fiscal issue this election cycle but few are talking about it.” We won’t repeat it again here.

But the ultimate point is simple.

The choice this coming session isn’t between the PFD and oil taxes. Even with increased oil taxes, Alaskan families will still have to contribute something. The real choice is between which families.

Using PFD cuts, just middle and lower income – working – Alaska families will be required to contribute. Using other, broad-based revenue approaches, all Alaska families (and non-residents) will bear a share of the burden.

The choice should be clear. All Alaska families (and non-residents) should be required to contribute, equitably. Regardless of how it deals with oil taxes, the coming Legislature should adopt, and the governor should sign, legislation that accomplishes exactly that.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

There are other views besides keithleys. Consider publishing those as well. Maybe less bias……

“ All Alaska families (and non-residents) should be required to contribute, equitably.”

Which group is this biased against?

Brad: It would be very useful to read an explicit discussion of what a progressive income tax would look like to generate revenues on the order of a billion dollars a year, which seems to be ballpark what will be needed to avoid using permanent fund revenues. Your July 22 column doesn’t really paint that picture.

I’m afraid that a reasonable income tax will be inadequate, although it should still be part of a diverse revenue pool.

The 2017 ITEP study does an analysis, using the version of the progressive income tax considered by House Finance that year, of what it would take to raise $500 million. The study was designed to be scalable, so just double the rates to get $1 billion. https://itep.org/comparing-the-distributional-impact-of-revenue-options-in-alaska/#.WQCKodIrLQC As a result of various bells & whistles, that approach is sharply progressive, with a much higher marginal rate at the upper end than we think is necessary. As we’ve discussed in other columns, we believe a much more equitable (and politically palatable) approach is a flat (rate) tax, which by spreading the… Read more »

Thanks. The ITEP study is informative. I’ll gladly pay my share of the progressive income tax. I was expecting it to be more onerous than that.