Last week’s column focused on conducting a “thought experiment” on the Permanent Fund (Fund). It examined what would have happened if the balance of the Fund had been invested in an exchange-traded fund (ETF) replicating the Standard and Poor’s (S&P) 500 index as of the beginning of Fiscal Year (FY) 2020, instead of the way it was actually invested over that period by the Permanent Fund Corporation (PFC). Because of its solid reputation, strong following, and very low cost, we used Vanguard’s S&P 500 ETF as the alternative.

The “thought experiment” created an eye-opening comparison. The numbers showed that in the five short years plus a few months for which we ran the numbers, the balance of the Fund would have grown to nearly $40 billion (almost 50%) more if invested in Vanguard’s S&P 500 ETF than the balance resulting from the Permanent Fund’s actual approach.

However, as some pointed out after reading the column, we didn’t perform the key calculation they thought necessary to make the point: translating the difference in the balances into what it means in terms of the annual percent of market value (POMV) draw made by the Legislature from the Fund. In short, the key question to them was not the Permanent Fund balances but how much was being left on the table compared to the current approach in terms of annual state revenue.

This week’s column is designed to answer that.

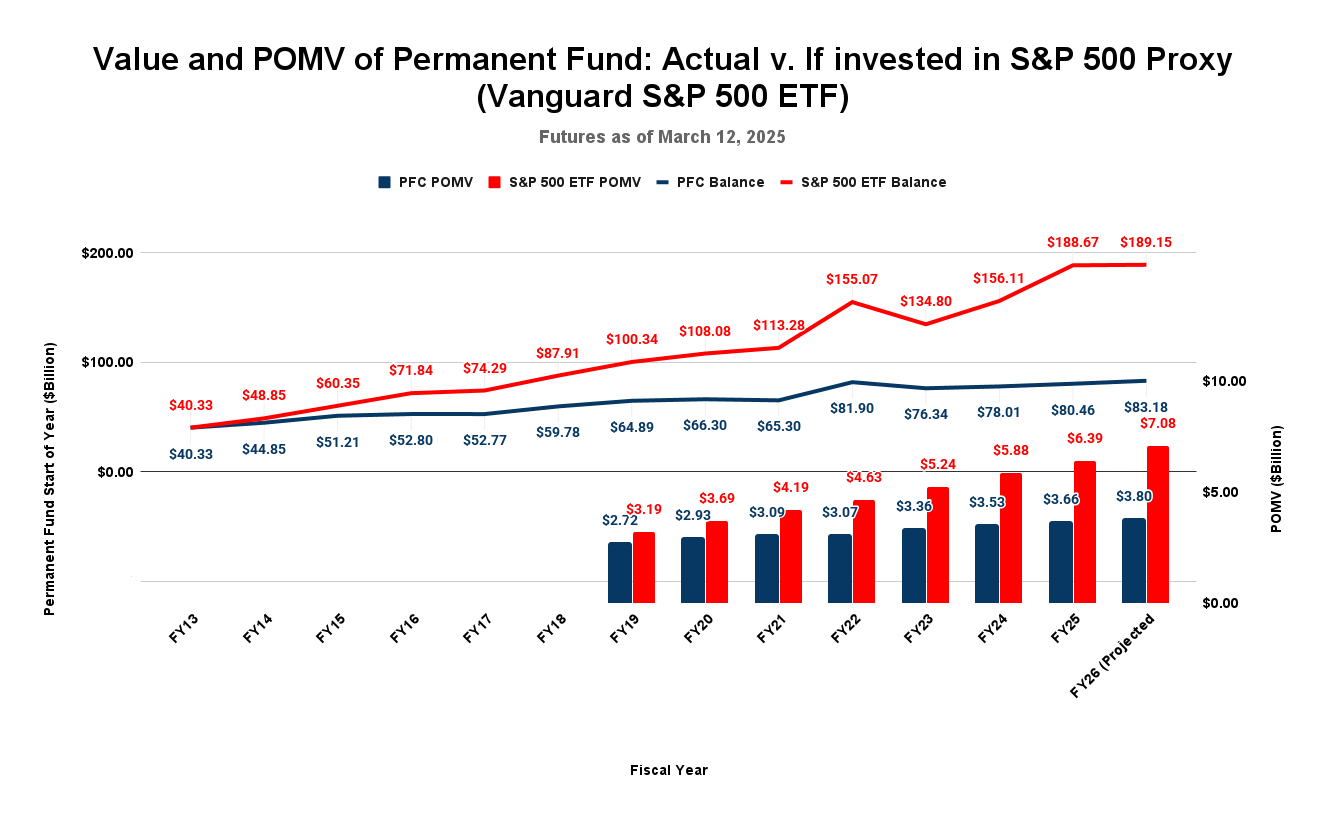

To do that, we have restated the balance of the alternative fund using the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF as of the beginning of FY13 and progressed it forward from there. We use that date because, under current law (AS 37.13.140(b)), the level of the annual POMV draw is based on “the average market value of the fund for the first five of the preceding six fiscal years, including the fiscal year just ended.” The POMV draw began in FY19. To have the requisite history to calculate the alternative as of the same year, we need to restate the balances of the Fund under the alternative approach from the beginning of FY13.

We calculated those levels using the same approach as last week’s column. We start the balance of the S&P 500 alternative at the same level as the actual Fund effective July 1, 2012. The balance of the Fund at that point was $40.33 billion. From there, we have grown the balance of the S&P 500 alternative by the total growth rate calculated using the tool available at Total Real Returns, adjusted for the same transfers into (royalty) and out (PFDs) actually made by the PFC up until FY19 – the start date of the POMV draw. After that date, we have matched the level of the net transfers out of the S&P 500 alternative to the level of the POMV draws the alternative would have supported.

Using the S&P 500 alternative, the fund’s value would have grown to $188.67 billion (the red line) by the end of FY24/beginning of FY25, more than double the balance of the actual Fund (the blue line) at that point ($80.46 billion).

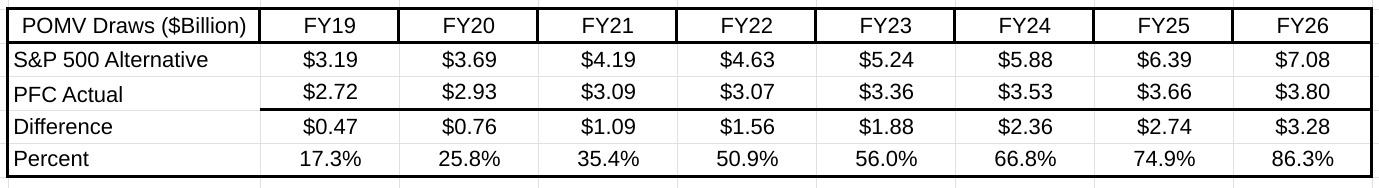

While not as dramatic, given the lag created by the 5-year averaging approach, the POMV levels under the S&P 500 alternative would also have been significantly higher. Beginning in FY19, the amount available for the POMV draw from the fund under the S&P 500 alternative (red bar) would have been $3.19 billion, approximately 17% higher than the $2.72 billion actually available. In FY20, the amount available for the POMV draw under the S&P 500 alternative would have been $3.69 billion, more than 25% higher than the $2.93 billion actually drawn.

For the current year (FY25), the amount available for the POMV draw under the S&P 500 alternative would be $6.39 billion, nearly 75% higher than the $3.66 billion actually drawn. The amount available for the POMV draw for next year (FY26) under the S&P 500 alternative would be $7.08 billion, more than 85% higher than the $3.80 billion available from the current Fund.

Here are the differences by year:

Not to put too fine a point on it, but those differences would have been more than enough to enable paying both a full PFD as calculated under the current approach and enacting the original version of HB 69 (this year’s K-12 funding bill) with more than a little bit still left over.

They would also be enough to silence all talk of ending the Fund’s current two-account system: the corpus and earnings reserve. The only reason for that proposal is that the PFC currently isn’t generating enough earnings to cover the existing POMV draw. As a result, some propose merging the two accounts to enable draws from the corpus to cover the difference.

The S&P 500 approach would have generated more than enough funding to cover the draw over the long term. By investing in an ETF, all the PFC would have needed to do to fund the draw was to sell the requisite number of VOO (the ticker shorthand for the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF) shares when required to cover the withdrawals.

One criticism we heard of last week’s column is that the S&P 500 is “volatile,” meaning that values based on it can move dramatically over a short period either up or down. While the S&P 500 certainly is not nearly as volatile as other market tools, admittedly, it is more volatile than the current Fund. We made that clear in last week’s column by comparing the year-end levels of the S&P 500 alternative for FY22 and FY23. As we said there, “over that period, the value of the [S&P 500 alternative] plunged by 13.7% compared to only 6.8% for the actual Fund.”

But in itself, volatility is not disqualifying. Indeed, it can be a very good thing.

While there have been ups and downs, from the starting point (FY13) through the end of FY24, the balance of the S&P 500 alternative has grown by over 365%, while the actual Fund has only grown by 100%. Every year since the start, the ending balance of the S&P 500 alternative has been higher than the ending balance of the actual Fund. While the Fund certainly is less volatile, that’s mainly because it has grown less, plodding along year after year within a fairly narrow band.

In short, accepting the increased volatility of investing in the S&P 500 alternative would have resulted in higher returns.

Moreover, the PFC’s hedges against volatility have not actually protected the Fund from drops. Just as did the S&P 500 alternative, the actual Fund suffered its own loss of value over the course of FY23.

The Permanent Fund is unlike an individual retirement fund, where investors decrease risk as the fund matures to ensure sufficient funds are available to cover retirement when it occurs. Instead, like any endowment, the Permanent Fund has an infinite life with a smoothed payout averaged over an extended period. This positions it to ride out any increased volatility as long as, over the long term, the volatility is rewarded with higher returns.

Also, avoiding volatility like the PFC has done – by relying heavily on managers and advisers – can be very expensive.

As we said, one of the advantages of an ETF is that it is very low cost. Vanguard’s current “expense ratio” (annual fee) is .03% of the fund’s value. Even at a year-end value of $169.38 billion, that’s only $50 million. By comparison, as of the end of December 2024, the PFC’s fees are running at an annualized cost of $860 million on a base less than half of the S&P 500 alternative. The one-year savings in fees alone of $810 million – almost exactly 1% of the PFC’s market value – more than pays for a lot of marginal volatility.

We do not necessarily suggest investing 100% of the Fund in the Vanguard (or any other) S&P 500 ETF. These columns have only been to evaluate the impact of doing so.

As we said in last week’s column, “setting the mix at the standard ‘Buffet Rule’ 90 (equity)/10 (bond) split or even at a much more conservative 60/40 split,” would reduce volatility, but still achieve return levels significantly above those that the actual Fund has achieved. As importantly, trimming the approach with bonds could be done while still preserving the cost advantage of using ETFs. For example, the expense ratio on Vanguard’s Total Bond Market ETF (ticker: BND) is also .03%.

But we think that these charts make a point that, when translated into the POMV draw, the PFC’s current approach is costing both the state’s private and government sectors opportunities that the additional cash could provide. In our view, under its current approach, the Fund is being managed much too conservatively and much, much, much too expensively, both of which are costing the state real money in terms of lower POMV draws. Over time, the PFC has become more like a high-cost, self-sustaining bureaucracy than the efficient revenue-generating financial machine the state needs at this point.

Given the state’s current fiscal situation, we believe the state should thoroughly rethink the PFC’s approach going forward. Failure to do so will continue to cost the state and Alaskan families money at a time when they can ill afford it.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

“…….They would also be enough to silence all talk of ending the Fund’s current two-account system……..”

Nothing “silences all talk”. We even see “thought experiments”. Political reality means political struggle, especially over public resources. Period.

You should use bitcoin instead. Bitcoin is up 30,000%+ since 2013.