“Thought experiments are defined as the mental process of using hypotheticals to logically reason out a solution to a difficult question. As the name suggests, thought experiments often try to simulate the experimental process through imagination alone.” – The Decision Lab

Recently, we have been writing often about the Permanent Fund (Fund) and the various issues that are increasingly associated with it. One issue is the level of returns it has been generating under its current management. In one of our most recent columns on the subject, we focused extensively on the performance of the Fund against various benchmarks, not only those created by the Permanent Fund Corporation (PFC) to self-measure its own performance but also against common external benchmarks, such as Standard & Poors (S&P) 500, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA), and the Nasdaq 100.

After stepping through the comparisons, we concluded that:

[While] comparing the Permanent Fund’s performance only against the PFC’s self-selected benchmarks leaves the impression that everything’s ‘sort of ok’ … the Permanent Fund’s average performance over the period against the broader context provided by the S&P 500 leaves an entirely different impression. The takeaway is that using the current approach, the PFC is leaving money on the table compared to the results if all—or at least a significant part—of the Permanent Fund were invested in an S&P 500 mutual fund or ETF.

Subsequently, some have asked us to better define what we mean by “leaving money on the table.” The questions have largely been about magnitude: Is it a little bit or a lot?

To answer those questions, we have been working on a thought experiment comparing the Fund’s current level to the level it would have been if, instead of how it was, the Fund had been invested starting at a certain point in one of the alternatives. Following up on the discussion of the S&P 500 in the earlier column, we have focused on examining the results if the Fund had been invested in an exchange-traded fund (ETF) designed to track that index’s return.

Investors can’t invest directly in the index because it’s just a reported calculation, like the weather. However, they can invest in ETFs or mutual funds that invest in the same stocks used in the index in approximately equal weights, which, as a result, generally produce the same results. From a cost perspective, ETFs are typically preferable to mutual funds because they are usually passively managed and, thus, less expensive.

For this thought experiment, we have used Vanguard’s S&P 500 ETF, which is usually referred to by its trading symbol “VOO.” We have used it because it has a solid reputation for accurately tracking the index and a strong following, with over $1 trillion in assets. It also provides a very low cost to investors, with a current expense ratio of only .03%. For those reasons, it is regularly preferred over other S&P ETFs.

For the experiment, we have assumed that, effective as of the first day of Fiscal Year 2020, the balance of the Fund was invested through the purchase of VOO shares instead of continuing to be invested as it was. We then track what would have happened and compare it to what actually happened to the Fund as invested by the PFC.

In calculating the comparison, we have made two adjustments as we have gone along. Vanguard’s S&P 500 ETF pays periodic dividends. Using the tool available at Total Real Returns, we have calculated investment growth as if the dividends are reinvested, the same approach used generally by the PFC within its portfolio. The second are adjustments for the net transfers into and out of the Permanent Fund. The transfers in are for royalty deposits; the transfers out are for the percent of market value (POMV) draw. We adjust the ETF fund for both transfers to make it subject to the same financial ebbs and flows as the Fund.

In calculating the transfers, we have used the amounts for each reflected on the PFC’s financial statements. We have also used the PFC’s financial statements to track the value of the Fund as it was actually invested over time.

We have not made adjustments to replicate the costs charged against the Fund on the PFC’s financial statements. One advantage of an ETF is that it does not involve the costs of active management. The current .03% expense ratio covers Vanguard’s costs of managing the ETF, which are already reflected in the VOO share price. While some minor costs would be involved at the PFC level in monitoring the ETF fund and selling and buying shares at the time of the transfers, they would likely be lost in the rounding of the overall performance.

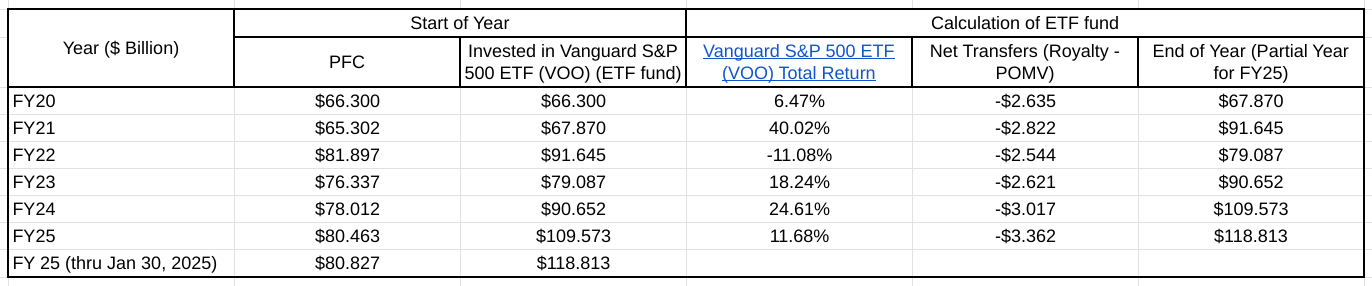

Here’s the year-by-year growth of the two funds over the period:

In calculating the level of the ETF fund, we have grown (or depreciated) the level of the fund at the start of the year by the total return for the year, less the amount of the net transfers (royalty deposit minus POMV withdrawal). We have assumed that the transfers are spread over the course of the year rather than made entirely at the beginning or the end. In years with positive returns, the year-end number would be smaller if we assumed the transfers were entirely made at the beginning of the year and higher if we assumed the transfers were made entirely at the end. Assuming they are spread out over the year is closer to reflecting the Fund’s actual experience.

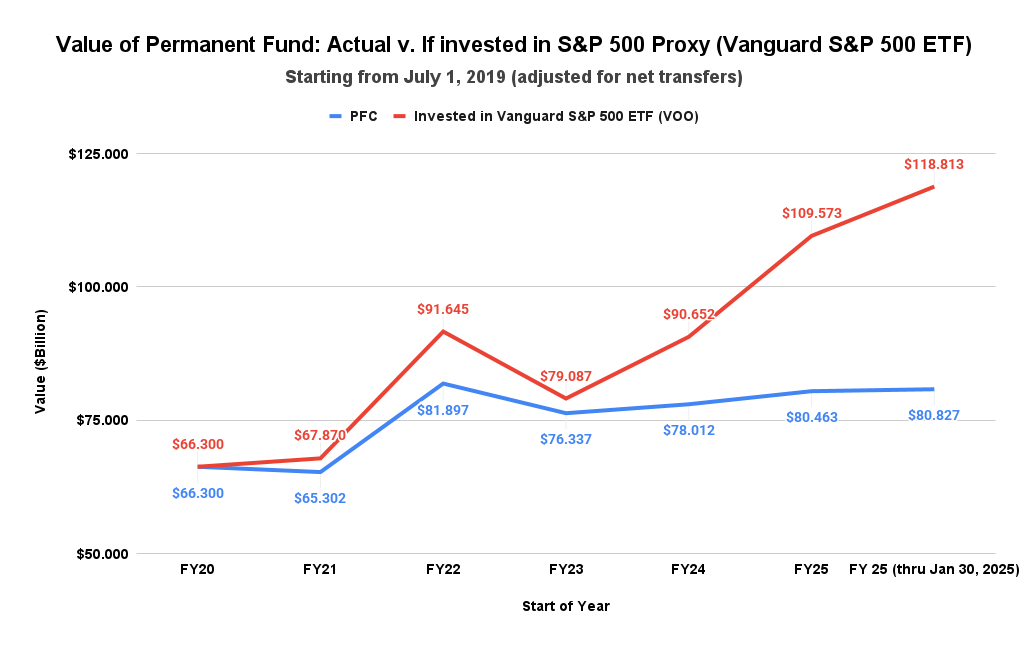

Here is the result graphically:

To be honest, the results are jaw-dropping. Investing all of the fund in Vanguard’s S&P 500 ETF at the beginning of Fiscal Year 2020 would have produced higher end-of-year balances in every subsequent year. Through January 30, 2025, the fund would have grown by over $50 billion, approximately three and a half times the amount that the Fund actually grew. The overall growth over the 5+ years from the starting to the ending point would have been nearly 80%, compared to the actual growth of the Fund over the period of approximately 22%.

Of course, in the real world, investors generally avoid investing all their money in stocks because of their volatility and risk. The type and level of risk is reflected on the chart by comparing the year-end levels of the ETF fund for FY22 ($91.645 billion) and FY23 ($79.087 billion). Over that period, the value of the ETF fund plunged by 13.7% compared to only 6.8% for the actual Fund. The Fund is designed to mitigate that risk by trimming its investment in public and other equities with investments in lower risk bonds and other fixed return assets.

However, risk mitigation can also be achieved through low-cost ETFs. For example, Vanguard also has a Vanguard Total Bond Market ETF (trading symbol BND), which focuses on intermediate-term bonds and whose “objective is to seek to track the performance of a broad, market-weighted bond index. ” This ETF can be – and often is – used to diversify the risks of stocks in a portfolio. Like VOO, BND has a current expense ratio of only .03%.

Over the period from July 1, 2019 (the beginning of FY 2020) through January 31, 2025, Vanguard’s S&P 500 ETF had a total gross (before transfers) return of 123.63% (an average of 15.5%/year). Over the same period, Vanguard’s Total Bond Market ETF had a total gross return of 1.31% (an average of 0.23%/year). Setting the mix at the standard “Buffet Rule” 90 (equity)/10 (bond) split, the overall gross return over the period would have been 111.4%. Even at a much more conservative 60/40 split, the overall gross return over the period still would have been 74.7%. Both are substantially higher than a similarly calculated overall gross return over the period for the actual Fund.

As we noted at the outset, the purpose of a thought experiment isn’t necessarily to arrive at a solution but to generate ideas for problem-solving. The Permanent Fund is currently facing several challenges. Actual returns have been lower not only than its own self-created benchmarks but also lower than the POMV draw rates, leading some to call for restructuring the Permanent Fund to enable access to the corpus. Management fees have been running significantly higher than seems reasonable compared to peers. And given the complexity of its active management approach, transparency has been limited.

In addition, the state is facing a significant budget crisis, which is increasing the focus on the Fund’s ability to produce higher returns.

We believe the thought experiment (or what economists might call the “counterfactual”) undertaken in this column helps identify some ideas for solving those problems. Adopting an investment strategy that focuses broadly on tested and successful indices rather than specific investments may help produce the higher return levels needed not only to help lessen the severity of the state’s budget crisis but also to solve the problem of return levels lower than those required to meet the state’s annual POMV draw. Using ETFs would significantly reduce the management fees the PFC is currently incurring. And by lessening the complexity of the Fund’s current approach, using ETFs would increase transparency and, thus, trust in the PFC’s management of the Fund.

But even if it doesn’t do any of those things, at least this column has created another tool for assessing the Fund’s performance. We will continue it in the future by incorporating ongoing updates into our monthly review of the Fund’s financials.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Nevada PERS does just this. They have a total of two employees and they simply invest in broad, low cost stock and bond indexes. Net of fees they blow most public investment houses out of the water. Getting fancy with alternative investments comes with high fees and the need for $300,000+ employees to manage it all. You really need to be beating the market significantly to justify those fees. That “missing” $38 billion would be producing an extra $2 billion per year from the POMV.

Hand the whole thing off to Fidelity or some management business that knows what they are doing!

Perfection is a far-fetched expectation, and government of any kind is a ridiculous method to attempt fo achieve said perfection.

Interesting analysis. It would be more instructive to the non-economist reader, if the analysis had comparisons of other time frames, i.e., 10-year; 15-year. Would probably reinforce conclusion.

This was a great breakdown — super detailed and backed with real numbers, which makes it all the more convincing. That “what if” with VOO is a serious eye-opener. It’s wild to see just how much more the fund could have grown with a lower-cost, passive ETF strategy, and honestly, the simplicity of that approach makes it even more appealing. I’ve been looking into these kinds of comparisons more lately, especially around ETF-based strategies and risk-adjusted returns. Traders Union has been a solid resource for that — they break down platforms, fees, and trading tools in a way that actually… Read more »

Totally agree with you — the data in this piece really speaks for itself. What stood out to me too was how clearly it shows the potential impact of just switching to a simpler, more cost-effective strategy. A lot of funds overcomplicate things, and it doesn’t always translate into better results. Also +1 on that resource you mentioned: https://tradersunion.com/ — I’ve used it myself and found some genuinely useful breakdowns, especially when comparing brokers or trying to get a better grip on spreads and hidden fees. It’s been helpful for sorting through the noise when testing out different platforms. Would… Read more »