In last week’s column we took a first look at Governor Mike Dunleavy’s (R – Alaska) proposed FY23 10-year Plan. As those who read the column will recall, we concluded that the Plan both wasn’t sustainable and, with respect to projected spending levels, unrealistic. If, as the saying goes, a budget reflects your values, the values that emerged were to prioritize “gimmicks” (making spending appear smaller than it is by failing to use realistic adjustments) over candor.

This week we take a look at what it would take to make the FY23 10-year outlook both realistic and sustainable.

In doing so, we rely heavily on a piece of the Department of Revenue’s “Fiscal Plan Model” (DOR Model) published in early November. We must admit that, at first, we weren’t a fan of the DOR Model. That was because, on the revenue side, it incorporates the oil prices projected in DOR’s “Preliminary Fall 2021 Revenue Forecast” with little flexibility for detailed, year-by-year adjustment. As we noted in a previous column, those oil prices are largely unusable because they stray far from current market levels.

But it turns out the spending side of the DOR Model is much more helpful. While not exactly the same down to the penny, the 10-year spending levels used as a baseline in the DOR Model come close enough to those included in the FY23 10-year Plan to provide some useful insight into what impact certain adjustments permitted by the DOR Model may have on the spending levels contained in the FY23 10-year Plan.

The most important of these is the inflation factor. Reflecting the apparent goal of the Dunleavy administration to significantly suppress future spending levels without making actual cuts, both the DOR Model baseline and FY23 10-year Plan use ultra low adjustment factors in their calculation of future spending levels. The DOR Model, however, provides users with a tool to apply different inflation rates at a topline level. (The DOR Model does not enable the user to see where inflation is being applied, so it may understate the impact to some degree, for example, by not applying inflation to the baseline capital budget. But after doing some basic checks, it seems to come close.)

In our effort to adjust the FY23 10-year Plan for reality we have looked at two, more realistic inflation factors. The first is the 2% inflation factor currently used by the Permanent Fund Corporation in its projections, which also is the average long run rate targeted by the Federal Reserve Board. The second is the current, 2.5% “10-Year Breakeven Inflation Rate” reflected in the Treasury securities market.

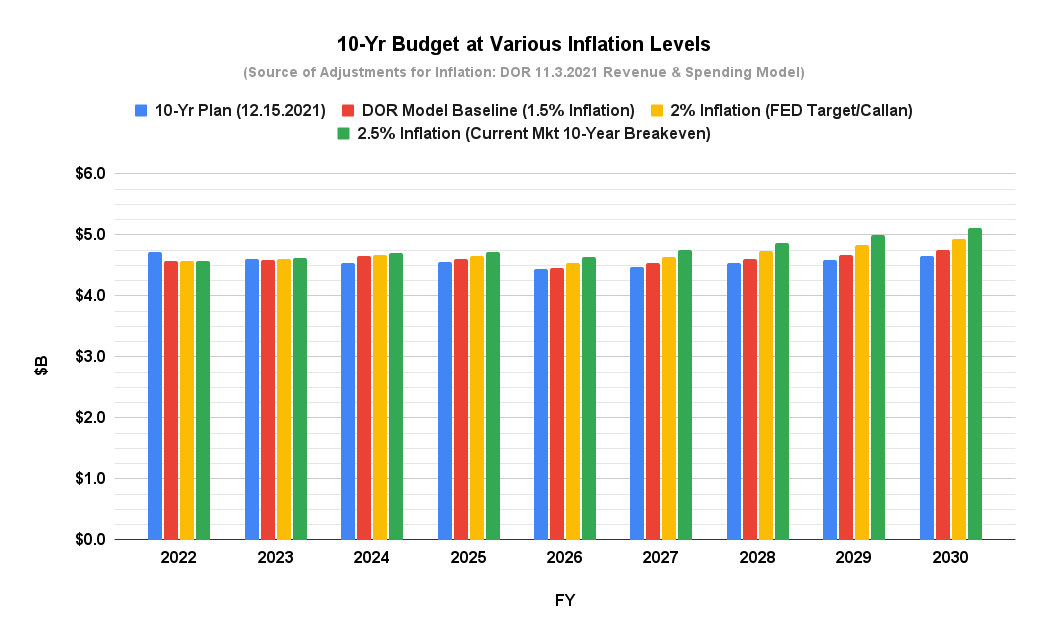

Here are the 10-year spending levels that result from each (compared to the levels reflected in the FY23 10-year Plan and the DOR Model baseline). We note that these projections retain all of the spending reductions – such as the reductions in retirement accruals and the expiration of the reimbursable oil tax credit program – included in Governor Dunleavy’s proposal. As contemplated by DOR’s Model, they simply adjust what remains for inflation:

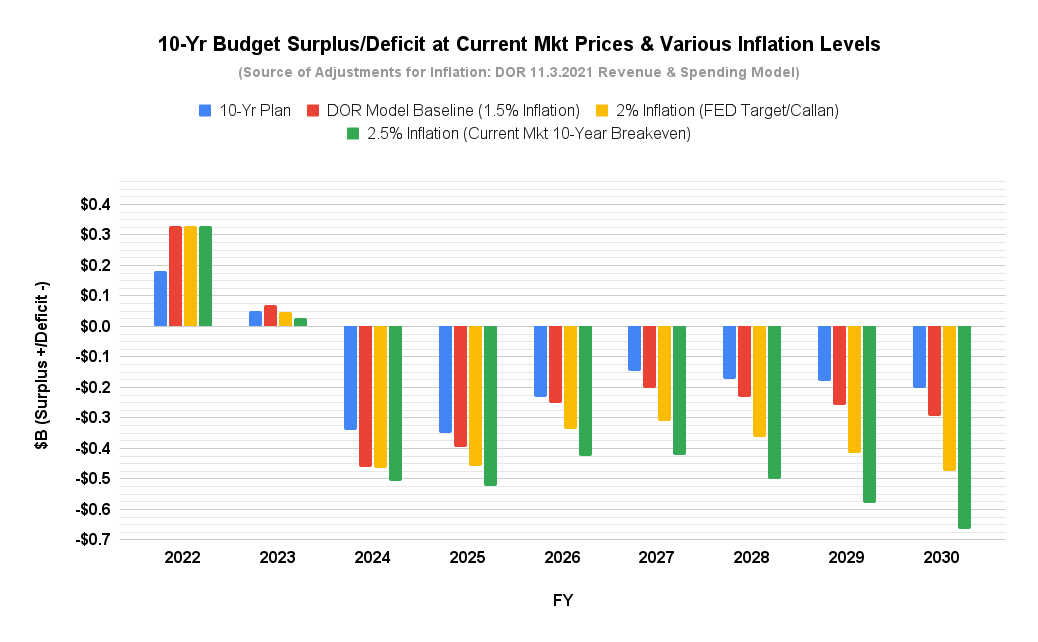

Applying projected revenues calculated at current market oil price levels and using the POMV and unrestricted federal revenue “adjustment” levels included in the FY23 10-year Plan, the yearly budget surplus and deficit levels under each alternative are as follows:

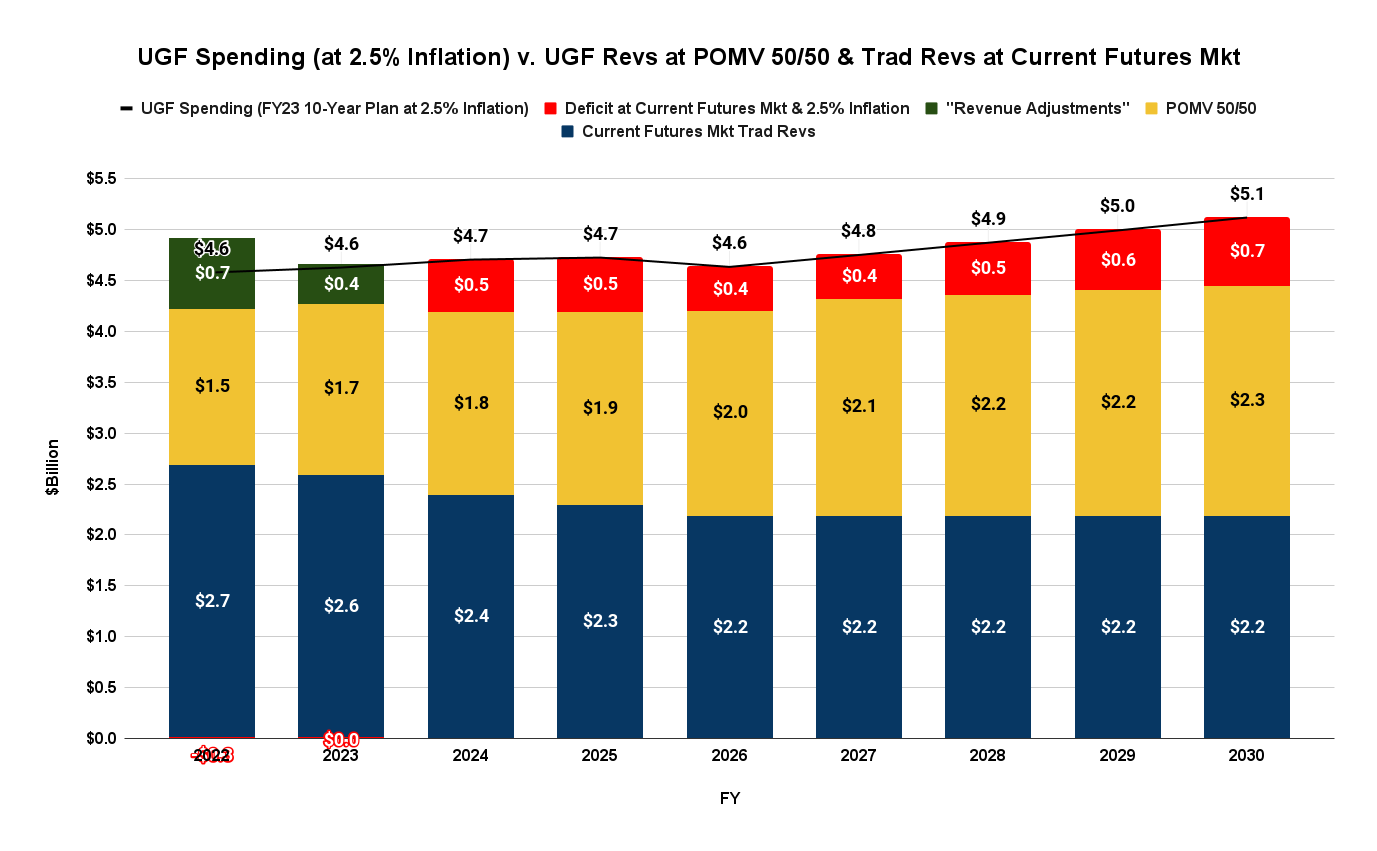

Because it reflects current market expectations, we believe the current market 10-year breakeven (2.5%) is the more realistic inflation adjustment. Restating the FY23 10-year Fiscal Plan (thru 2030, the same period covered by DOR’s Model) with that adjustment results in this, we believe, much more realistic 10-year outlook:

Not even the Dunleavy administration would argue that the CBR is “healthy enough” to bridge those deficit levels. As a result, other steps are required to offset the deficits in order to make the state’s fiscal position sustainable.

Some will immediately say “spending cuts.” But the administration hasn’t proposed any other than the change in the retirement amortization rate and the expected expiration of the reimbursable oil tax credit program. Moreover, as the Legislature’s Fiscal Policy Working Group concluded in its August 2021 Final Report, the most realistic scenario is “reductions in the $25-$200 million range over multiple years … realized through structural and statutory reforms that maintain levels of service but improve efficiency.°

While, if achieved, those would help reduce the above deficits, they don’t eliminate them.

At the opposite extreme, others will immediately say “PFD cuts.” But as we have explained in a previous column, of all of the various revenue options, PFD cuts both have “the largest adverse impact on the economy,” and are “by far the costliest measure for Alaska families.” Sustainability isn’t measured solely by whether a budget balances, but whether it’s done in a way that both enhances the economy and treats all Alaska families equitably. PFD cuts fail both tests.

Besides, in proposing to restructure the PFD by replacing the current statutory formula with POMV 50/50, the governor already has baked into his base budget an average PFD cut over the next decade of roughly $600 million/year (the difference in the inflation adjustment between the two approaches we discuss further here). For those that want a contribution from the PFD as part of an overall fiscal solution, that’s a permanent, 25% cut in the statutory PFD, an already substantial contribution.

Instead, our view is that it’s time to turn to developing additional revenues (or phrased more accurately, substitutes for even deeper PFD cuts) as the appropriate next step in achieving a sustainable, long-term budget. At least at some level, the administration must think so as well because included as part of the DOR Model is the ability to toggle various “revenue options,” such as changes to oil taxes, adopting a sales tax and increasing the current fuel tax.

Based on our analysis of the realistic budget deficit above, we believe the level of substitute revenues required to achieve a sustainable budget is in the range of $500 million per year, the average of the projected deficit levels from FY24 through FY30 using the 2.5% inflation factor.

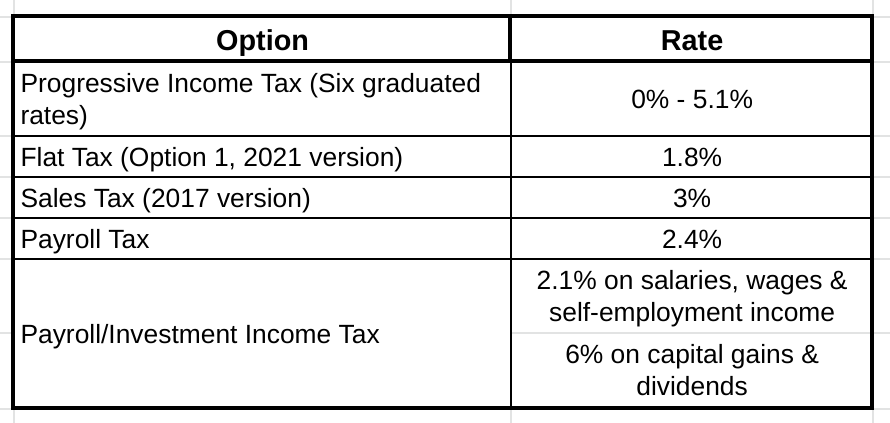

Interestingly, the Legislature already has a detailed analysis of what is required from various options to achieve that level of revenues. Both the 2017 and 2021 studies done for the Legislature by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy of various revenue options are readily summarized at that level.

Each of these levels could be reduced if, as part of an overall package, the Legislature and administration agreed concurrently on budget reductions, the adoption of one or more of the other revenue options included in the DOR Model, or both.

As we’ve discussed generally in a previous column, each of these options have different impacts on the overall economy and Alaska families. We will look at them more specifically in the context of the revised 10-year outlook in next week’s column.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Brad, the problem with any income tax is you run the risk of driving away the people who will actually pay it. One of the biggest draws when I recruit people to Alaska is the lack of an income tax. There are plenty of examples of states that have driven people away with taxes. NY and MD come to mind. You can argue the income tax you propose is modest but it really is not. And AK is already a hard enough place to bring in employees. People will pay a premium to live in CA or HI although that… Read more »

Big B.

How correct you are. Also having no state tax relieves us of another tit for government employees to suck on for ever.

There are plenty of examples of states that have driven people away with taxes. NY and MD come to mind. You can argue the income tax you propose is modest but it really is not. Really, at 2.5% the flat tax he is proposing is extremely, ridiculously modest. The latest piece of failed legislation based on this rate would hit everyone making more than the amount of the federal standard deduction — about $12,500 for a single person and $25,000 for a married couple. The average flat tax in the 9 states that have one is 4%. That’s 60% higher… Read more »

NH makes a lot of money on alcohol sold to MA residents. And the state liquor stores are right behind a toll booth. Sales taxes are allowed in AK but get stopped at the state level by areas that have them. A sales tax would not bother me. Keithly blows off cutting spending in this piece which remains a huge problem. Our spending remains 2-3x per capita of other states.

Exactly. NH doesn’t leave anything on the table. They’re certainly not using their savings for everyday operations as we do, or to gift free services to nonresident businesses & investors and then telling their own citizens, “Sorry, we can’t afford quality law enforcement or education.” Comparisons of Alaska’s per-capita spending to that of other states is meaningless until you adjust for federal money, the amount of money we’re giving away to Outsiders & foreigners, our vast land mass, our small population, our location, our geography, and the high cost of goods and services here. If you want to see what… Read more »