In this week’s column, we continue to analyze elements of Governor Mike Dunleavy’s (R – Alaska) proposed fiscal plan by comparing the administration’s initial (Initial) and revised (Revised) Fiscal Year (FY) 2027 10-Year Plans, examining the impact of the administration’s proposed increase in the minimum oil production tax rate against previous tax levels and on revenues, and thinking through some alternatives for balancing the budget in the decade ahead.

At the end, we also include a brief, preliminary look at one aspect of the new study of Alaska’s fiscal options by the University of Alaska-Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER). To avoid overload, we will defer a deeper dive into the study until next week, but, especially in light of some statements made at yesterday’s hearing on the Governor’s proposed plan before the House Finance Committee, we think one finding warrants special emphasis now.

I.

We begin by comparing the administration’s Initial and Revised FY2027 10-Year Plans because the administration proposed to raise significant revenue in the Initial Plan through “new revenue measures.” We have examined the Revised Plan to assess how the administration has followed through on its proposal.

The results are disappointing. In the fiscal note accompanying Senate Bill (SB) 227, the administration’s proposed omnibus revenue measure, the administration projects the amounts it expects to raise over six years (FY2027 – FY3032) from its components. As many have noted, on their face, the projected revenues in that fiscal note are significantly short of the revenue projections in the Initial FY2027 10-Year Plan for the “new revenue measures” it contemplated.

In response to questions about the shortfall, the administration has said that it “expects that revenue from oil production and a proposed trans-Alaska natural gas pipeline” will fill the remaining gap.

But that’s not what is reflected in the administration’s Revised FY2027 10-Year Plan. While in the Revised Plan, the administration projects that the deficits included in the Initial Plan will decline significantly over the period covered by the Plan and, indeed, produce surpluses during the four years from FY2031 through FY2034, it’s not because of increased revenue either from SB227 or increased oil production and the Alaska LNG project.

Instead, the projected deficit reduction under the two plans is primarily due to two factors. The first is restructuring the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) from its current statutory approach to a 50% draw of the annual percent-of-market-value (POMV) from the Permanent Fund (POMV 50/50), as proposed in the administration’s SJR23. The second, surprisingly, is additional cuts to projected spending levels for government services, mainly in the operating budget, beyond those already included in the Initial Plan.

The Revised Plan reflects very little additional revenue beyond those sources included in SB227.

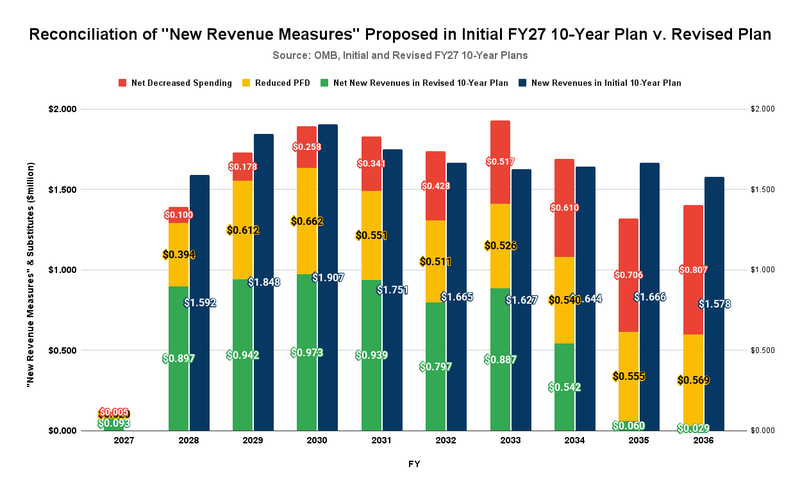

In the following chart, we compare projected revenues from the “new revenue measures” in the Initial 10-Year Plan (dark blue bars) with the measures used to close the same level of projected deficits in the Revised Plan. The projected revenues from the new revenue measures proposed in SB227 are shown in the green bars. The impact of the PFD restructuring proposed in SJR23, reflected in the Revised Plan as a reduction in “use of funds” for the PFD relative to the levels in the Initial Plan, is shown in the yellow bars. The net decrease in spending between the two plans is shown in the red bars.

While the proposed new revenues included in SB227 and the deficit-reducing impact of changing the basis for the PFD from the current statutory approach to POMV 50/50 are legitimate “new revenue measures,” closing the remainder of the projected deficits through additional spending cuts is disingenuous. The Initial Plan already projected limited growth in spending, slightly below the projected inflation rate. The Revised Plan drops that rate of growth by two-thirds, to an average level of less than 1%, to make up the difference between the legitimate “new revenue measures” included in the Revised Plan and the level of “new revenue measures” promised in the Initial Plan.

The administration deserved considerable credit for being forthright in the Initial Plan about the need for “new revenues” to meet tight, but reasonably projected, spending levels. It has squandered some of that, as push has come to shove, by hiding to a significant degree behind additional, unrealistic real (after-inflation) spending reductions.

II.

The administration’s headline claim that it is proposing to increase the overall “minimum” oil production tax rate from 4% to 6% is similarly disingenuous.

As we have explained in previous columns, the state’s effective oil production tax rate, expressed as a share of gross wellhead revenues (ex-royalty), as calculated from the Department of Revenue’s (DOR) Fall 2025 Revenue Sources Book (Fall 2025 RSB), is projected to fall significantly over the coming decade from 6.7% in FY2025, and an average of 6.8% in the decade before that, to an average of 3.3% over the period from FY2026 – FY3030, and an average of 1.9% over the period from FY3031 – FY 3035.

Those are the projected levels even under the current 4% minimum tax. Some have speculated that the shortfall is attributable to increased exploration and production costs (what DOR refers to as “deductible lease expenditures”) projected to be incurred by producers over the period. But it’s not. Those costs don’t reduce the tax base, which DOR refers to as the “Gross Value at Point of Production,” against which the “minimum tax” is applied. The “minimum tax” is calculated before those deductions are applied.

Instead, as we explained in the previous column, what appears to be driving the effective production tax rate below the minimum is the increasing impact of provisions related to “Gross Value Reduction” (GVR) volumes. As explained in the Fall 2025 RSB, GVR volumes are those produced from “newly developed units, as well as certain new producing areas or expansion of producing areas.”

Producers generating those volumes are entitled to a related reduction in taxable revenue, as well as a tax credit of $5 per barrel that can be applied even against the minimum tax floor. As output of that type of production grows, so does its adverse impact on production tax revenues.

Of course, not all production volumes qualify for GVR treatment, and the proposed increase in the minimum tax would likely have some effect on some of the other volumes, but that’s not enough to drive the state’s overall effective production tax rate up to the 6% minimum rate headlined in the administration’s proposed SB227.

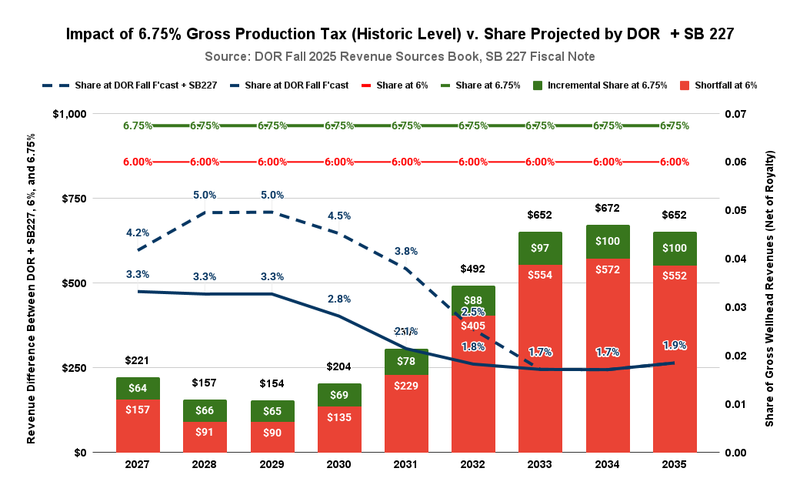

In the following, we chart the share of gross wellhead volumes projected to be received as oil production taxes over the 10 years included in the Fall RSB, under the law as currently in effect, as well as under the provisions of SB227.

Under current law (the blue solid line), the state’s effective tax rate on gross wellhead revenues is projected to fall from 3.3% in FY2027 to 2.1% in FY2031, and subsequently to 1.9% in FY2035. Despite the so-called 4% “minimum tax,” the annual average effective production tax rate projected over the period is only 2.4%.

That would increase somewhat under SB227. The state’s share would increase above current-law levels to 4.2% in FY2027 and 3.8% in FY2031, before falling back to 1.9% in FY2035 as the proposed temporary increase in the minimum rate expires. But while it increased somewhat, the annual average effective tax rate over the period would still be only 3.4%, well below the current “minimum rate.” On average, oil production taxes would increase by approximately $130 million annually during the period in which the proposed “increase” in the minimum tax rate remained in effect.

Especially in the later years of the period, however, that increase pales in comparison with the levels achieved if the effective rate were raised across all volumes to an actual minimum of 6% for the whole period, or, better yet, as we suggested in the previous column, restored to the 6.75% level experienced by the state in the first decade under SB21, the state’s current oil production tax code. In the chart, the red bar represents the incremental revenue impact relative to the levels projected under SB227, assuming the actual minimums were raised to 6% across all volumes. The green bar represents the incremental revenue impact above that if the production tax were set at a simple rate of 6.75% of gross wellhead revenues (net of royalty).

Over the years SB227 is proposed to remain in effect, raising the overall minimum to 6% would increase average annual revenue by an additional $184 million, for a total annual impact of approximately $315 million. Over the same period, resetting the rate to the historic 6.75% level would, on average, yield an additional $72 million annually, for a total annual impact of approximately $387 million.

As we have explained in previous columns, SB21 is badly broken. Instead of the temporary, incomplete patch proposed in SB227, the Legislature should focus on permanently addressing the underlying issue. Restoring the overall tax rate permanently to the 6.75% level experienced over the last decade would increase average annual revenues by approximately $475 million relative to the levels projected in the Fall 2025 RSB.

III.

While the administration’s proposal falls short, the Legislature actually has the tools at hand to resolve the persistent fiscal gap Alaska has endured over the past decade and is projected to continue to face in the decades ahead.

Rather than seeking a single sweeping fix, the key lies in taking a series of smaller steps.

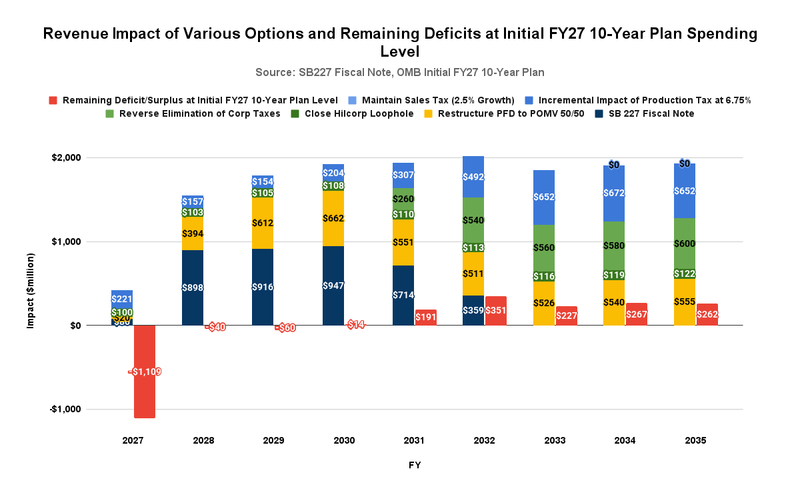

In the following chart, we plot the effect of combining several small revenue steps to address the deficit levels identified in the administration’s Initial FY2027 10-Year Plan. They include:

- The revenue-generating steps proposed in SB227, the administration’s proposed omnibus revenue package;

- Restructuring the PFD to POMV 50/50, as proposed by the administration in SJR 23;

- As we have discussed in previous columns, closing the so-called Hilcorp Loophole;

- Reversing the elimination of the petroleum and general corporate income taxes proposed in SB227; and

- Resetting the state’s production tax rate at a simple 6.75% of gross wellhead revenues, the same average effective rate realized during the first decade of SB21 and as recently as FY2025.

As the chart demonstrates, once fully effective in FY2028, these five steps would serve to eliminate the deficits projected in the administration’s Initial FY2027 10-Year Plan, and, indeed, build a small current revenue surplus, which could be used finally to start repaying past borrowings from the Constitutional Budget Reserve (CBR) in the years ahead.

As the chart also shows, using this combination of revenue sources would allow the state to allow the seasonal sales tax to expire midway through FY2032, as proposed in SB227. Alternatively, the state could continue to maintain the sales tax indefinitely, using the proceeds either to accelerate the required repayment of the CBR or to substitute for other revenue sources, such as a reasonable reduction in, but not the elimination of, the corporate income tax.

IV.

Finally, in recent comments, including some made yesterday during the initial House Finance Committee hearing on SB227, some appear to assume that the sales tax proposed in SB227 would stack on top of continued deep PFD cuts, as one legislator subsequently put it, “increasing the cost of living for Alaska families.”

That’s not correct. Under the Governor’s proposal, revenues from the proposed sales tax would serve as a substitute for continued PFD cuts of the same amount, thereby significantly reducing the impact of raising revenue on middle- and lower-income families (together, 80% of Alaska families).

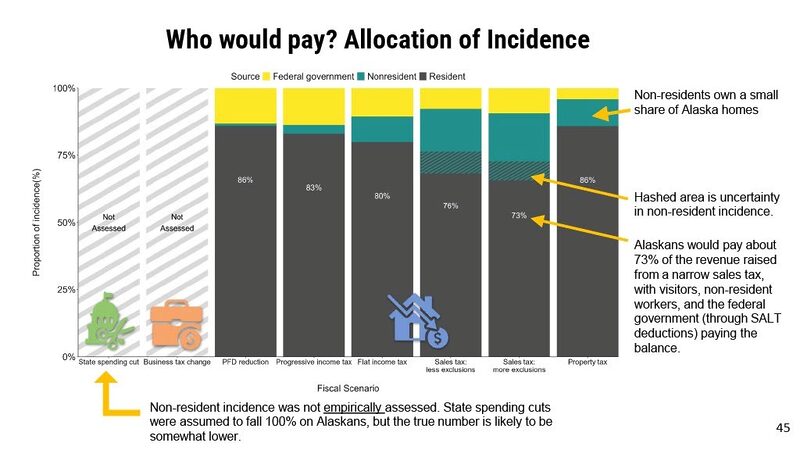

Three charts from ISER’s newly released study, “Economic Impacts of Alaska Fiscal Options 2026,” illustrate the point. The first two concern the relative share of the revenue burden borne by Alaskans across the various options.

The first chart examines the share of the revenue burden under the main options evaluated in the study: PFD cuts, income taxes, sales taxes, and a statewide property tax. As the chart shows, while Alaskans bear 86% of the cost of revenues raised using PFD cuts, they bear less, indeed, increasingly much less, if the same amount of revenue instead is raised through income and/or sales taxes. The difference is largely borne by non-residents, in the same way that Alaskans bear some of the revenue burden of other states when they pay sales (or income) taxes in those states while visiting (or working) there.

Substituting either of those sources for PFD cuts to raise the same amount would reduce the overall impact of raising the revenue on Alaska families. Alaska families would have more income in their pockets than under PFD cuts, because non-residents would bear a larger share of the overall burden.

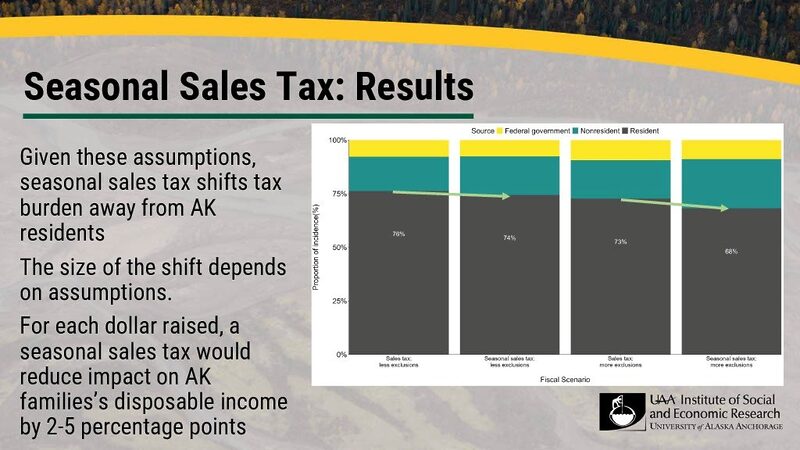

The second chart continues the first by examining the relative impact on Alaskans and non-residents of some additional alternatives.

The Governor’s proposed seasonal sales tax is the second bar from the left: “Seasonal sales tax: less exclusions.” Compared with bearing 86% of the cost of revenue raised through PFD cuts, Alaska families would bear only 74% under the alternative approach. By substituting the second approach for the first, Alaska families would retain 12% of the income currently withheld from them and diverted to the state through PFD cuts, reducing “the cost of living for Alaska families” rather than increasing it.

As the chart shows, Alaska families could save an additional 8% if, instead of the “Seasonal sales tax: less exclusions” approach proposed by the Governor, the Legislature adopted the “Seasonal sales tax: more exclusions” option, shown on the far right.

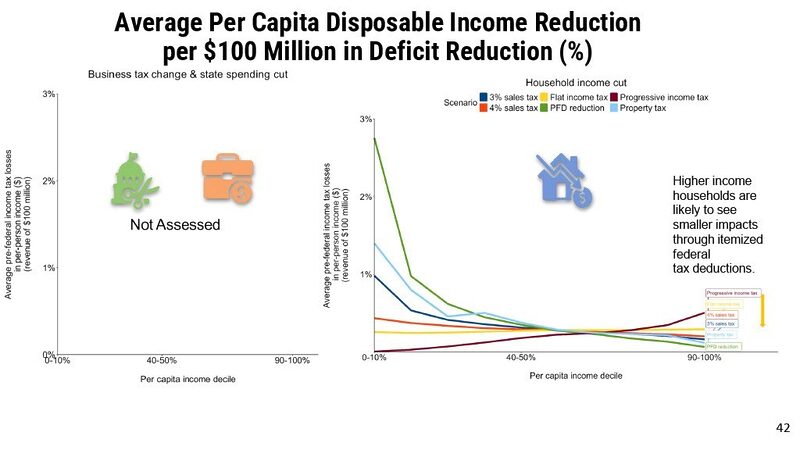

The third chart largely reflects the same impact as the first two in a different way. This chart examines the effects of the options on Alaska families, showing the percentage of income lost by income bracket. The various options are substitutes for each other. Using one to raise a given amount of revenue avoids the impact of using the others.

Starting on the left, the chart shows that raising revenue by cutting PFDs (the green line) takes a much larger share of income from those in the lower-income brackets than a sales tax with broader exclusions (the red line). Although difficult to appreciate on the scale of the chart, the calculations confirm that the relationship persists across the middle-income brackets.

In short, the charts show that under almost any alternative, raising revenue to offset the same amount of continued PFD cuts would materially reduce the revenue’s impact on middle- and lower-income Alaska families, lowering “the cost of living for Alaska families” rather than increasing it.

As we indicated previously, we will have more to say about this and other issues examined by the new ISER study in next week’s column.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.