In the middle of a recent column on the Anchorage Daily News (ADN) op-ed pages ostensibly about Thanksgiving, “long-time Alaska journalist, with breaks” for other things, Larry Persily wrote this:

I expect the biggest debates next [legislative] session will be how much more the state should spend to support public education — and how much the state should spend to increase the amount of the Permanent Fund dividend [PFD]. That’s the way it’s been for years — all the other issues fall away as lawmakers and the governor fight over the two largest items in the budget.

It’s nostalgia at its worst. It’s a sad, repetitive menu, made unhealthier by the governor and his supporters putting a large dividend above all else. They pledge a bigger PFD than the state treasury can afford, knowing they won’t win in the Legislature but will win with many voters. It’s my cynicism acting up again.

Framing the state’s fiscal issue as “support for public education” versus the PFD is a theme that Persily, along with numerous others, including the ADN’s own editorial board as well as some legislators, often uses.

But it’s not accurate.

The real issue is not “x” versus “y.” The real issue is how to pay for “x.” Diverting money statutorily designated for distribution as PFDs is one way. But as we’ve explained in previous columns, there are a number – indeed, a large number – of other and better (from the standpoint of the overall Alaska economy and Alaska families) ways.

There are some characteristics of PFD diversions that make them an easy target.

First, they largely only take dollars significant to middle and lower-income Alaska families. Those in the top 20% income bracket contribute a trivial share of their income, and non-residents (and thus, industries relying significantly on non-resident workers) and oil companies escape, as former Governor Jay Hammond once put it, entirely “scot-free.”

Thus, it is much easier for legislators to tap politically. Middle- and lower-income Alaska families are largely unorganized before the Legislature. As a result, they aren’t well-positioned politically to push back on fiscal measures directly targeting them. Borrowing a phrase from economics, they are “price-takers.”

On the other hand, the top 20% includes not only legislators’ most significant donors but also, thanks to their recent pay raise, all of the legislators themselves. Moreover, both the industries relying significantly on non-resident workers (such as tourism and commercial fish) and oil are very well represented and organized.

Again to borrow an economics phrase, combined, they are Alaska’s “price-makers.” Politically, any revenue measures that even moderately include them would face stiff resistance. It is much easier for legislators to target middle and lower-income families through PFD cuts.

Second, PFD diversions are something uniquely within the Legislature’s control. Unlike other forms of revenue, such as new taxes, diversions don’t require the governor’s signature to enact. Indeed, despite their statutory foundation, the governor can’t even restore the diverted amounts through a veto of the Legislature’s actions. As a result, all that is needed to raise that particular form of revenue is for the Legislature to convince itself as part of its overall budget process.

Like the remainder of Alaskans, the governor – the state’s only statewide elected official and who is constitutionally envisaged to act as a counterpoint to the Legislature when appropriate – is left largely as a bystander. As it has repeatedly demonstrated since 2017, the Legislature doesn’t need to deal with him on the issue.

Third, unlike other forms of revenue, PFD diversions are variable. Other forms of revenue, again like taxes, largely are set at fixed amounts and, once fixed, serve effectively as a moderately hard cap on available revenues. Again, as former Governor Hammond put it, “the best therapy for containing malignant government growth is a diet forcing politicians to spend no more than that for which they are willing to tax.”

Efforts to increase those sources of revenue require going back through the process of convincing the Legislature and then the governor, both of whom must then stand for reelection based on their reaction.

On the other hand, at least up to the full amount of the PFD, amounts raised through PFD diversions can be changed easily from year to year to fit the desired level of government growth. One year, the Legislature can divert a portion consistent with the so-called POMV (percent of market value) 50/50 approach. The next year, if it needs more, it can simply change the basis for the diversion to the so-called POMV 25/75 approach. And if that’s not enough the following year, it simply can change the basis for the diversion again to the so-called “leftover PFD” approach.

Effectively, to borrow another phrase from former Governor Hammond, there is no “Sword of Damocles” hanging over legislators’ heads as they move from one level to the next. As long as they convince themselves of the “need” for the additional money, they can make it happen without any material constraints.

But there are significant reasons why PFD cuts, though easy to implement, are the worst approach for the Legislature to take from the perspective of Alaska families and the overall Alaska economy.

First, as we’ve explained in previous columns, based on studies by both the University of Alaska-Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) and the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), PFD cuts are “by far the costliest measure for [80% of] Alaska families” compared to other revenue approaches. Indeed, as Professor Matthew Berman of ISER put it in a recent column of his own on the op-ed pages of the ADN, they are “the most regressive [revenue measure] ever proposed.”

Some, like former Senator Peter Micciche, sometimes attempt to dismiss this point by arguing that the impact shouldn’t be a concern because the state takes care of those at the low end of the income bracket in other ways. But much of what they use as examples – e.g., SNAP (food stamps) and Medicaid – are funded either entirely or significantly from federal funds, not state funding, and even then, apply mostly to those only in the lowest 20% income bracket.

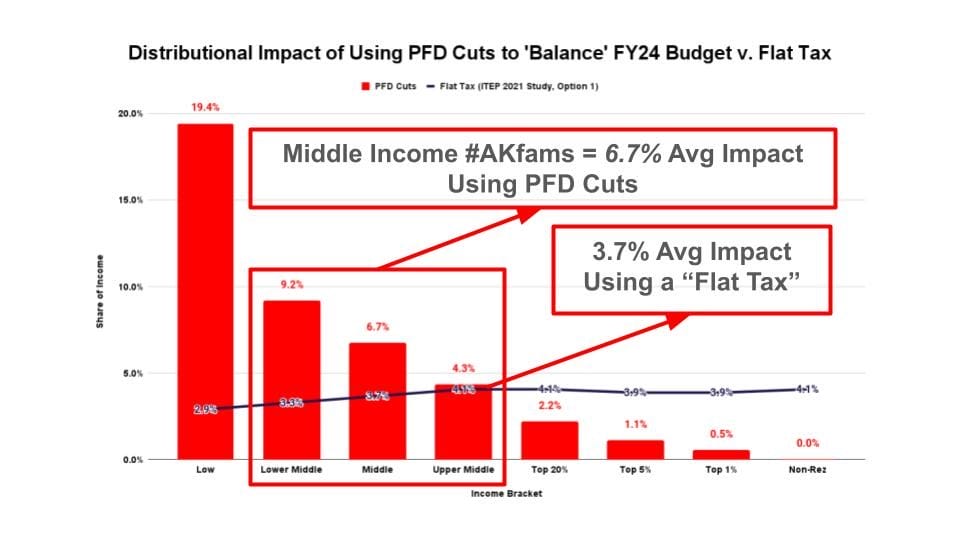

Those who seek to dismiss the point intentionally ignore the similar adverse impact of PFD cuts on the 60% of Alaska families that fall in the middle-income brackets (low-middle, middle, and upper-middle), whose income also is reduced by more than would occur using other approaches but who do not benefit from similar offsets. As an example, the following charts the impact on the middle 60% of Alaska families of using PFD cuts versus a “flat tax.” There is no offsetting state-funded “safety net” that closes that gap.

Closing the deficits and paying for additional programs using PFD cuts are similarly “by far the costliest measure” to them.

Second, as we’ve also explained in previous columns based on studies by ISER, using PFD cuts to fund government compared to other revenue measures also has “the largest adverse impact on the economy.” Similar to its impact on middle-income Alaska families, diverting PFDs to support government spending also reduces state income and jobs more than other revenue alternatives.

Again, some sometimes seek to dismiss this point, in this case, by arguing that the ISER study on which it is based focused only on the “short-run” impacts of PFD cuts.

But that, again, intentionally ignores the fact that the two bases for the finding about the adverse impact of PFD cuts – that “the impact of the PFD cut falls almost exclusively on residents, and it is highly regressive” – are long-run in nature. The effects of other factors included in the ISER studies may evolve over time, but the economically regressive nature of PFD cuts – that their impact grows larger the farther down the income scale they apply – and the fact that they only raise revenue from Alaskans – and not from non-residents – don’t change.

The ISER study’s conclusion on this point remains the same whether looked at over the short or long term.

Third, unlike other approaches that bring new money into the Alaska economy to help pay for government costs, using PFD cuts largely shifts current dollars around. As the ISER study makes clear, adopting a broad-based tax, like a sales or flat income tax, would bring in new money from non-residents that otherwise is leaving with them to other states. Adjusting oil taxes would retain money for use in the state that, ultimately, otherwise is being distributed broadly to shareholders in other states and nations.

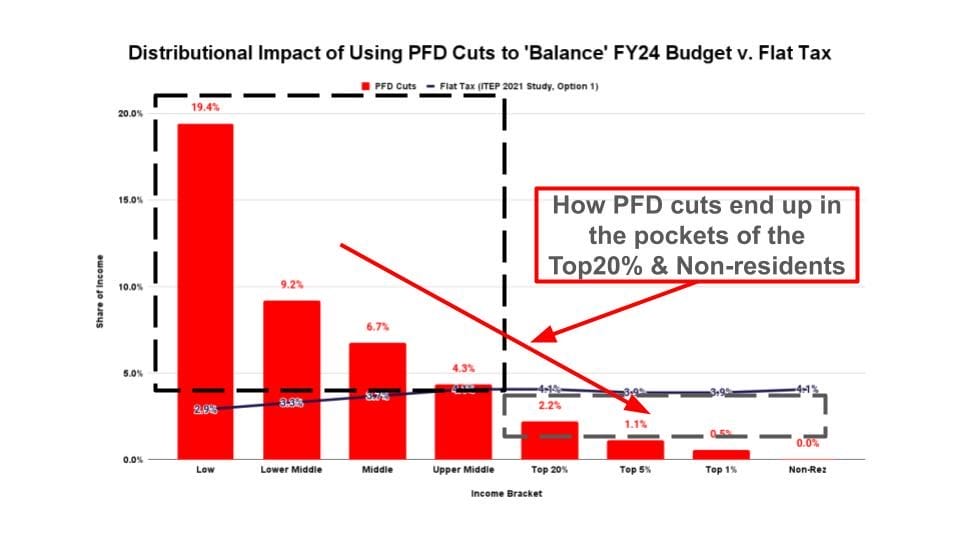

Using PFD cuts, on the other hand, diverts money from the pockets of largely middle but also lower-income Alaska families into the pockets of those in the top 20%, non-residents, and oil companies by saving them from being taxed to pay an equitable share instead. If anything, it ends up bleeding money from the state. Put graphically, it has this effect:

Again, some sometimes seek to dismiss this point, in this case, by arguing that, when paid as PFDs, the money is subject to federal income tax and, thus, there is “leakage” outside to the federal government. But as Professor Berman explained in his ADN op-ed, and as we explained further in a subsequent column, there are ways to significantly reduce that impact to levels well below the new money being raised from non-residents and oil companies.

If implemented, the net effect is to bring significant amounts of new money into the state rather than, as occurs by relying on PFD cuts, merely upstreaming the money from one set of pockets in the state largely to another.

In short, while PFD cuts may be one option for paying for increased “support for public education,” they are not, as Mr. Persily seeks to imply, the only way. Nor are they even the best way.

Instead, they are the way that has the “largest adverse impact” of all the revenue options on the overall Alaska economy and are “by far the costliest measure for [80% of] Alaska families.”

Ultimately, their only value is that they are, perhaps, the most politically expedient way and the way that best serves the interests of those in the top 20%, non-residents (and the industries tied to them), and the oil companies.

Those characteristics, however, aren’t even remotely sufficient to justify treating them as the preferred approach, and they certainly aren’t sufficient to justify treating them as the “sole-source” approach to solving the state’s fiscal issues.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Somebody’s got to say it: this feature has been a broken record for some time now. Everyone who reads the Landmine has made up their mind. Time to move on.

Yes, it’s a “broken record,” and I skip the articles where he repeats his well-worn arguments. I’m trying to think of a phrase that would be more widely understood by people who did not grow up with LP’s that skip or repeat over a scratch in the vinyl. Perhaps “overused meme,” or “key stuck on the keyboard,” or “glitch in an NPC” (as in a non-player character).

I love the basic point here. It’s not either/or. But that also doesn’t mean that the idea of money going direct from the government to people isn’t related to our unwillingness to tax ourselves. Free money, and not wanting to pay for stuff because that means we will have to tax ourselves, is all very much bundled up in the same mentality. “We want our free money, and we don’t want to tax ourselves.”

What many don’t appreciate is that for 80% of Alaska families – including the 60% in the middle-income brackets – taxes take less from income than PFD cuts and are better for the overall economy to boot. Given that we have to deal with deficits somehow, the #NoTax mantra of many in those income brackets (or who otherwise are concerned about the economy) is self-defeating. The top 20% – who are better off with PFD cuts – laugh all the way to the bank at the assist.

And what Keithley doesn’t realize is that his message has hit a brick wall. A large portion of the Landmine readers are in the top 20%. The message needs to get out to the bottom 50%, and they’re not here.

Gimmee free money, gimmee free stuff, and don’t you dare tell me what to do…

It’s become an Alaskan tradition. If we are handing out free stuff, I tend to agree with this author about who should first get the treats – but untargeted welfare delivers moral hazard to all of us with minimal benefit.

The idea that government can not find any better way to spend its resources than handing out an annual fall bonus represents a profoundly pesimistic view of government.

Would you prefer that the top 20%, non-residents, and oil companies benefit from the free money instead? Because, as we explain here, it’s going to land somewhere and that’s the other option: https://alaskalandmine.com/landmines/brad-keithleys-chart-of-the-week-heres-how-and-how-much-of-the-pfd-cuts-are-ending-up-in-the-bank-accounts-of-non-residents-oil-companies/.

Brad- there are many options. We should all be taxed, and the tax should be progressive. We should protect immediate surplus to ensure it is spent wisely. The problem is that, in a state with a failing OPA, inadequately funded rural schools, deteriorating snow removal equpment and dangerous air quality, among other problems requiring financial investment, we have convinced ourselves that all of those uses of government resources is secondary to the distribution of free money. I have no interest in our state giving away crude oil to Conoco at a discount or failing to demand a tithe from those… Read more »

You consider the dividend check handout and the tax cut handout to be in opposotion to each other. I see them as being the same fundamental thing.