While because of its significance and Alaskans’ ability directly to control the outcome, we focus most often on these pages on the economic impact on Alaska families and the overall economy of cuts in the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) – what University of Alaska – Anchorage Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) Professor Matthew Berman has called “the most regressive tax ever proposed” – there are other economic distortions affecting Alaska families and the Alaska economy that also are worth attention.

A significant one is the impact of the Jones Act, a federal law that, as described by Investopedia, “requires goods shipped between U.S. ports to be transported on ships that are built, owned, and operated by United States citizens or permanent residents.”

While not dealing directly with the cost of shipping, by heavily restricting competition for the shipment of goods between U.S. ports to only those participants, the Jones Act is widely considered to significantly elevate prices – what some refer to as imposing a “tax” – in the market. Because of its higher dependence on goods shipped by water from Lower 48 ports, Alaska – and Alaskans – are among the most heavily impacted by the resulting higher costs for shipped goods.

In operation, the Jones Act creates an opaque – but nevertheless fairly direct – subsidy flowing from consumers who pay higher costs to certain groups. Who are the beneficiaries? Summarizing a large body of economic study, here’s what Chat GPT says:

U.S. Maritime Industry: The Jones Act provides protection and support to the U.S. maritime industry, including shipbuilders, shipowners, and operators. The requirement that vessels engaged in domestic trade be built, owned, and crewed by U.S. citizens or permanent residents helps sustain and promote these industries.

Shipbuilders: The construction of vessels that comply with the Jones Act requirements provides business and employment opportunities for U.S. shipyards. The act’s mandate for U.S.-built ships ensures ongoing demand for shipbuilding, supporting jobs and economic activity in this sector.

Seafarers: The Jones Act creates employment opportunities for U.S. seafarers. The requirement for U.S.-crewed vessels ensures that American sailors and other maritime workers have job prospects in domestic shipping. This helps maintain a skilled labor force within the maritime industry.

National Security: The Jones Act is considered to have national security implications. It ensures the availability of a domestic maritime industry that can be leveraged during times of war or other emergencies. Having a fleet of U.S.-built and U.S.-crewed vessels provides a strategic advantage by ensuring reliable and controlled transportation of goods and supplies within the country.

Environmental Protection: The Jones Act includes regulations that promote environmental protection in domestic shipping. U.S.-flagged vessels are subject to U.S. environmental standards, ensuring compliance with environmental regulations, including those related to pollution prevention and vessel safety.

Who pays the subsidy? Again summarizing a large body of economic study, Chat GPT generally categorizes those impacted this way:

Shippers: Companies that transport goods by sea between U.S. ports may experience increased transportation costs due to the requirements of the Jones Act. These costs can include higher freight rates, vessel chartering expenses, or increased operating expenses associated with using U.S.-built and U.S.-crewed vessels. Shippers may pass on these additional costs to their customers, potentially impacting the prices of goods.

Freight Forwarders: Freight forwarders, who arrange the transportation of goods on behalf of shippers, may also face higher costs when complying with the Jones Act. These costs can be passed on to their clients, which may include importers, exporters, or other businesses involved in international trade.

Consumers: Ultimately, consumers may bear some of the higher costs resulting from the Jones Act. When the costs of transportation increase, companies may adjust their pricing to cover these additional expenses. This can impact various sectors, including the transportation of goods, energy, and other industries reliant on maritime shipping. Consumers may experience higher prices for goods transported by sea within the United States.

But that only scratches the surface. Our focus is on which consumers – which Alaskans – end up paying the higher costs, i.e., the tax.

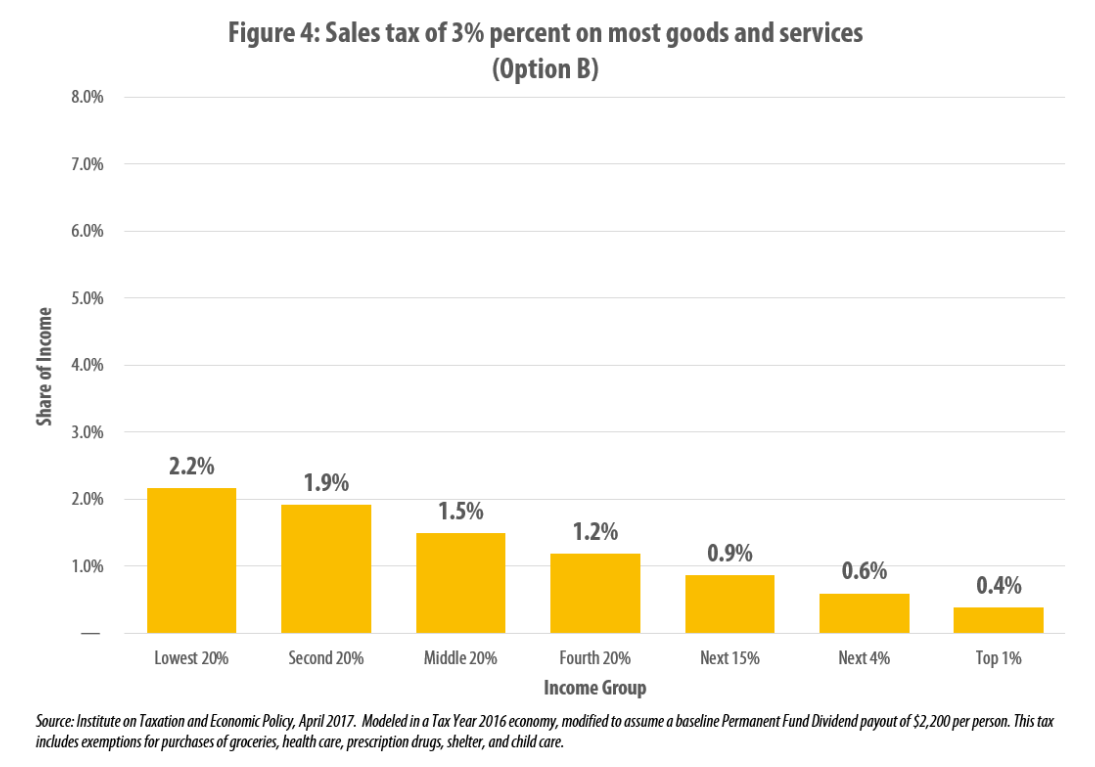

At first blush, the Jones Act operates somewhat similarly to a sales tax as an add-on to the cost of goods imported into the state from the Lower 48 by water. Based on previous work for the Legislature by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), we are clear about which Alaskans bear those costs.

As ITEP summarizes, “sales taxes tend to be regressive, impacting low- and middle-income families more heavily than high-income families when measured as a percentage of household income. This effect comes about largely because low- and middle-income families spend a larger fraction of their earnings on items subject to sales tax, while high-income families direct a large share of their income into savings and investments.”

But the added costs arising from the Jones Act are likely distributed even more regressively. While the added costs arising from a sales tax are set by law as a stated percent of the price of the underlying goods, those arising from the Jones Act are recovered as competitive conditions allow. That means a disproportionately larger share of the costs are likely recovered from less competitive and more price-inelastic markets.

In Alaska, that means the impact is likely disproportionately highest in the Interior and, increasingly, other rural parts of the state, with the largest impact in the Bush communities, which already also are among the most economically disadvantaged in the state.

Some attempt to argue that, at least at a high level, the Jones Act fairly taxes those consumers who are most reliant on interstate waterborne shipping. Their argument goes that those consumers benefit most from the Act’s “assurance” of a reliable source of waterborne transportation of goods and supplies within the country, especially during times of war or other emergencies.

But, as Dr. Berman says about the PFD, “let’s be honest.” At least as far as Alaskans are concerned, stripped to its economic essentials, the Jones Act is nothing more than an interstate subsidy flowing from Alaska consumers to shipbuilders, shipowners, operators, and seafarers overwhelmingly located in other states.

The Jones Act indeed may benefit national security, environmental protection, and other national objectives. It may make the nation safer and cleaner. But if so, the costs should also be recovered nationally through a transparent subsidy to the industry paid for broadly, including by the shipbuilders, shipowners, operators, and seafarers who directly benefit economically. Or perhaps, in part, through a tax on overseas goods delivered by the lower-cost, internationally flagged ships, which creates the purported need for a subsidy to maintain some domestically flagged and staffed vessels.

It shouldn’t be paid through an opaque wealth transfer largely from a narrow segment in the least competitive and most price-inelastic markets.

The industry, of course, heavily resists such a change. They are deeply concerned that if exposed to the light of day and spread nationally, Congress will decide that the costs aren’t worth the purported benefits, or at least that the costs should be minimized in some way.

To industry, it is much better to continue operating in the dark, collecting opaque subsidies derived from their heavily protected market position.

But let’s be clear who in Alaska is bearing the greatest burden of those costs. It’s largely middle and lower-income – working – Alaska families who are least well-positioned to bear the increased burden.

That’s the same group that, through the use of PFD cuts, is disproportionately bearing the costs of state government.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

The Jones act is one of the few pieces of legislation leftover from before the neoliberal’s deregulation agenda destroyed 90% of the good jobs in this country. Your same argument could be made about any protectionists manufacturing or farming laws in this country and has which is why we are in the position we are today. Although technically you are right my box of Cheerios might cost a nickel more I’d much rather it does and live in a country where people have good jobs building ships and being mariners.

Attempting to change the JA will result in bodies in the bay – and ultimately be unsuccessful.

“neoliberal’s deregulation agenda”

Goodness! Who know Reagan and all those Rs including P-Grabber are liberal, or, even neoliberal?

LOL

The column doesn’t call for the repeal of the Jones Act. It simply says that if we are going to have it, the costs it creates should be transparent and spread broadly rather than opaque and concentrated in non-competitive and price-inelastic markets.

Can foreign built boats be used for charter fishing

While I certainly appreciate that Chat GPT was cited in this piece, I’m not a fan of basing what I think upon information provided by a computer algorithm known for providing incorrect information.

The Jones Act is a relic of times gone by and should be sent to the scrap heaps.

Good article. Would be nice if maritime interests had an inclination to reform the Jones Act in favor of a subsidy. Until they get on board with some kind of reform, updating the Jones Act doesn’t seem to have any legs.

Thank you for bringing the attention to this from a different angle, as the basic economics has not landed with the entrenched interests for decades. This is what the Jones Act (1920) has achieved in maintaining and protecting the United States’ ability to compete in marine ship building and readiness, according to the industry itself: “The United States is the world’s largest trading nation and our national policy is to maintain a U.S.-flag merchant marine sufficient to carry our waterborne domestic commerce and a substantial part of our foreign commerce.[1] The portion of our Nation’s international trade carried on U.S.-flag ships,… Read more »