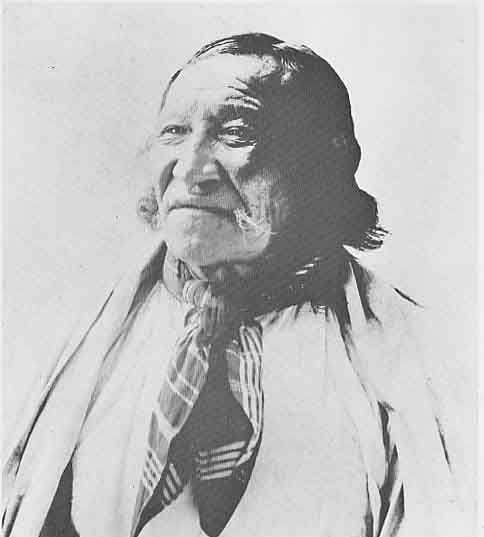

Sah Quah

More than twenty years after the American Civil War, an enslaved Alaskan walked into a Sitka courtroom and sued for his freedom

A project of the Alaska Landmine

Jeff Landfield | Paxson Woelber | Lee Baxter

August 8, 2022

On April 26, 1886, more than two decades after the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, a Haida man named Sah Quah entered a United States courtroom in Sitka. A judge later described him as a “sad spectacle” of a man, with mutilated ears and a missing eye. Sah Quah’s English was limited, but it would be impossible to ignore the gravity of his allegations: that he had been captured by the Flathead Indians and sold into slavery as a child, trafficked up a Northwest Coast slave-trading network, and was currently enslaved to a Tlingit man in Sitka named Nah-Ki-Klan. Sah Quah had come to the American court, he said, to seek “papers” freeing him from his bonds.

Alaskans today might be startled by the thought of a slave suing for his freedom in Alaska. Present-day local historical resources, educational curricula, and museum programming contain virtually no references to the practice of slavery in Alaska. However, an investigation by the Alaska Landmine suggests that this near-total historical amnesia demands reexamination.

In fact, chattel slavery played a central role in the cultures, politics, and economies of Southeast Alaska well into the nineteenth century, both before and after the acquisition of Alaska by the United States. Moreover, systems of enslavement persisted in Alaska long after slaves were constitutionally freed in the contiguous United States. These facts suggest a disturbing conclusion: that hereditary chattel slavery in North America did not end with the Emancipation Proclamation, or with the conclusion of the Civil War, or with the Juneteenth declaration, or even by treaty with Native American groups who held Black slaves.

Rather, it ended decades after these other events, here. In Alaska.

When slavery in Alaska did end, it did not do so with a blaze of wartime glory or with celebrated acts of the United States Congress. Rather, it ended as part of a process of colonial transformation that has saddled Alaska with generations of cultural pain and has left American law riddled with unanswered questions about tribal sovereignty. And into the middle of that process walked a downtrodden Haida man named Sah Quah, who stood before the American court on April 26, 1886 to demand his freedom.

I.

People of the Tides

To understand why slavery once thrived in Alaska, it is necessary to understand the geography of Alaska’s north Pacific coast, and the role of the region’s most iconic natural resource: salmon.

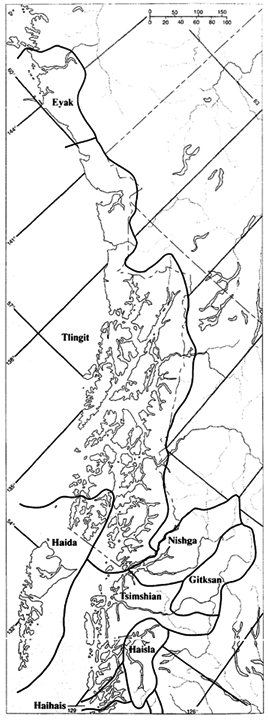

Trace the Pacific coast of North America on a map, starting in present-day Mexico and heading north, and one finds a relatively continuous line of long, arcing beaches interspersed with river outlets and arid headlands. There are few large natural bays and few offshore islands, leaving the majority of the coast unprotected from the brunt of the Pacific Ocean. But starting around present-day Northern California, the geography begins to change. Rainfall increases dramatically, and inland regions turn lush and green. Then, near present-day Seattle, the Coast Mountains intersect with the ocean and the coastline explodes into an intricate maze of bays, islands, fjords, and passages that stretches into Southcentral Alaska. Anthropologists refer to this area as the Northwest Coast.

Compared with much of the rest of western North America, the Northwest Coast was a place of incredible abundance. The cool, wet forests, intertidal zone, and rich marine ecosystems provided the groups that inhabited the Northwest Coast with a wealth of nutritious caloric sources. But there was one resource that guided the social development of the region more than any other: salmon. Every year, millions of the anadromous fish returned to the freshwater streams and rivers of the Northwest Coast where they had been born, sometimes in such numbers that waterways literally turned red. The relative regularity and scale of runs made salmon harvesting functionally little different from–and in some ways, nutritionally superior to–the farming of crops, and allowed the people of the Northwest Coast to reach levels of population and social and political organization more often associated with pre-industrial agricultural societies. What barley was to the Babylonian Empire, what rice was to the Zhou Dynasty, what maize was to the Aztecs, salmon was to the people of the Northwest Coast.

Most hunter-gatherer groups are characterized by nomadic lifestyles, relatively low population densities, and social customs that establish and reinforce egalitarianism between group members. But Northwest Coast cultures were nothing like this. The abundance of resources allowed coastal groups to establish densely populated permanent or semi-permanent settlements and towns, typified by elaborately-carved longhouses built from coastal timbers. Political matters and commerce between groups were adjudicated through an elaborate system of laws, customs, and kinship relations. The groups that predominated in present-day Alaska–the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian–developed highly codified and elaborate laws regulating private property ownership, including the ownership of intellectual property. Coastal groups developed successful maritime skills and technologies, and could project power or engage in mobile warfare with large parties of armed and armored soldiers. The Haida, for example, are often described as the “Vikings of North America,” inviting the retort that in fact, it is the Vikings who were the Haida of Europe.

One of the most notable distinctions between the Northwest Coast groups and traditional hunter-gatherers was the presence of pronounced social inequality. Anthropologists disagree on the precise nature of rank or caste in Northwest Coast societies, but all agree that social status played a central role in social organization. On the top were nobles, who slept in the best parts of communal homes, had access to the best food and other resources, and had a broad range of powers over other group members. In the middle were commoners who, though not as powerful as nobles, nonetheless still enjoyed autonomy and could achieve a good quality of life.

And on the bottom were the slaves.

II.

The Slaves

The practice of slavery was ubiquitous in indigenous Northwest Coast societies stretching from northern California to the Aleutian Islands. The earliest Western explorers noted the presence of slaves, and every indigenous language in the region includes a word for enslaved persons. Slaves and slavery are recurring and ordinary features of Northwest Coast mythology–including creation myths–and transcribed oral history. For example, “Haida Texts and Myths,” a 1905 collection of stories translated by the Haida chief Henry Moody and recorded by John R. Swanton, contains dozens of offhand references to slaves:

“She was a chiefs daughter at Djū.’ Her father had a slave he owned watch her. Then she said to the slave: ‘Tell a certain one that I say I am in love with him.’…”

“One whose father was a chief made gambling sticks. And one day he sent out his father’s slave to call any one who might choose to gamble… He continued to lose until he lost all of his father’s property. Then he lost the slaves, and when those were all gone he staked the rear row of the town…”

“The Tlingit destroyed Those-born-at-Stasaos in Skidegate channel. For that reason ten canoes went to war from Gū’dAl and three canoes of us came apart from the rest [when we were] among the Tlingit. Then they (the others) plundered. They destroyed a fort. On that account they had many slaves…”

The form of slavery practiced on the Northwest Coast is known as chattel slavery, meaning that enslaved persons were the chattel–or property–of their owner or owners. Slaves had no individual rights, and could be put to work, traded or sold, or killed at the sole discretion of their owners. Though reliable data is sparse, most estimates put the presence of slaves at between ten and thirty five percent of most Northwest Coast populations.

Unless a slave was freed, the condition of slavery was permanent and hereditary, and the children of an enslaved person would also be enslaved. Orphans, criminals, and those with gambling debts could be pressed into slavery. However, slaves were typically obtained through raids on rival groups, during which men of fighting age in the targeted community were often killed and women and children were taken as captives and enslaved. These raids were often conducted on near neighbors, but the advanced seafaring developed by Tlingit, Haida, and other Northwest Coast groups allowed them to conduct surprise attacks hundreds of miles from their homelands. In “Social Life and Social Structure of the Tlingit,” R.L. Olson describes a slave raid recounted in the mid-1900s by a Tlingit elder:

“The Tikana once came to the Chilkat country in 28 canoes to raid for slaves. They first came to the fishing camp called Tennane’h in Chilkat Inlet across the peninsula from Haines. All the men of that place except one named Ka’kink were away trapping marmot. A dog barked and gave the alarm. Kakink awoke and saw the raiders back of the houses. But he was able to escape to the beach, where he hid under a canoe. The women jumped into boxes and storage places. But the raiders captured 18 women, including the wife of the chief Tluctci’nk. They also carried away many dressed moose skins which had been traded from the Gunana.”

Once captured, high-status prisoners could be ransomed, but commoners, previously enslaved persons, or even high-status individuals who failed to be ransomed became the slaves of their captors. From that point onward, enslaved persons lost all prior status. Slaves were often forced to cut their hair short to distinguish them from commoners, and given slave names that were the intellectual property of their masters.

Slaves played a central role as status symbols–so much so that some early anthropologists concluded that slaves, despite their prevalence, were largely kept to bolster the prestige of their owners. However, evidence shows that slave labor also played a critical role in Northwest Coast economies. Slaves could be compelled to perform any labor demanded of them, including catching and processing fish, chopping firewood, hauling trade goods, carrying water, building houses, or paddling canoes. High-status women could have female slave attendants, and male slaves could be used as a private military force to project the power of their masters over commoners or rivals.

Though strict gender rules typically dictated what labor could be performed by men and women, these rules did not apply to slaves; male slaves could be forced to perform traditionally female work and vice versa. The appropriated labor of slaves was lucrative for the elite and freed up their time for ceremonial and cultural tasks, administrative work, or high-status activities like hunting marine mammals. In his 1928 work “Economic Aspects of Indigenous American Slavery,” anthropologist William Christie Macleod reaches the provocative conclusion that:

“The data available on prices in connection with the data on the percentage of slaves to the total population, distinctly suggest that slavery on the northwest coast among the natives was of nearly as much economic importance to them as was slavery to the plantation regions of the United States before the Civil War. Incredible as this may seem, it seems very definitely indicated by all the facts.”

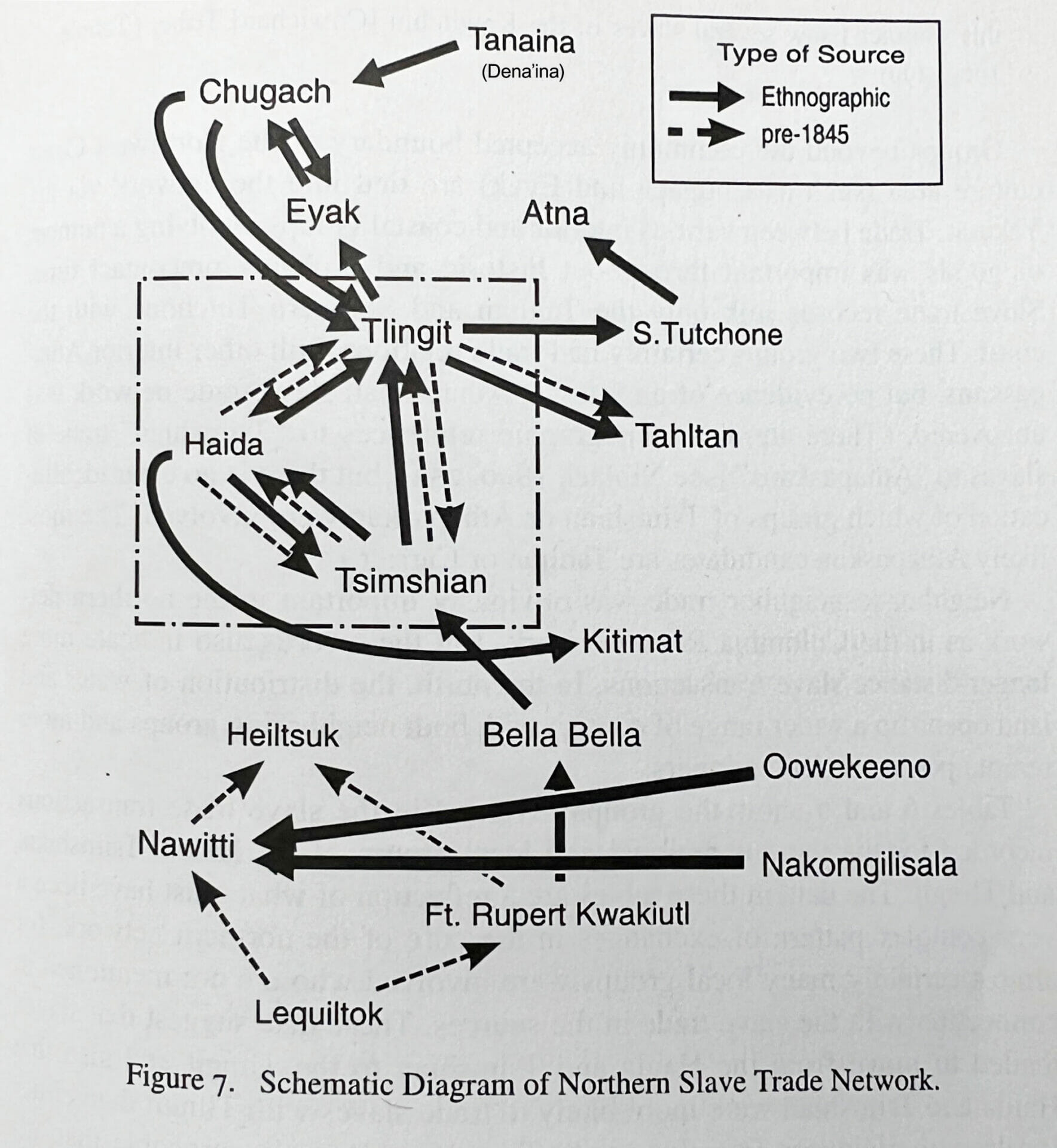

In addition to the economic value that they produced, slaves were themselves valuable trade goods. Slaves could be exchanged for other goods like animal skins or copper plates, given as gifts, used to pay debts, or exchanged for captives. The value of a slave fluctuated regionally and throughout time, and male slaves were generally worth significantly more than females. All records that indicate the trade value of slaves suggest that they were a highly valuable commodity, and a well-established slave trading network developed on the Northwest Coast, stretching from modern-day California to southcentral Alaska.

Though the core of the northern slave trading network centered on the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian territory in modern-day southeast Alaska, slaves were so valuable that even tribes that did not typically keep slaves themselves enslaved and sold their rivals. Early Russian fur traders noted that many Tlingit slaves were Flathead (also called Salish) Indians, who had been enslaved and traded far up the coast. Individuals were enslaved as far north as Dena’ina territory, which encompasses the Cook Inlet region and present-day Wasilla, Palmer, and Anchorage, and trafficked south to the Chugach on the Kenai Peninsula.

Slaves who had been trafficked long distances found it difficult to escape, and risked the threat of recapture or re-enslavement by other groups. But social pressure also played a key role in preventing runaways. Slavery was a condition of extreme shame and degradation, and even those who successfully escaped and returned home faced punishing stigma. This stigma could last for generations and could deeply stain the reputation of important families. In 1880, Canadian geologist and surveyor George Dawson wrote of the Haida in Haida Gwaii (Queen Charlotte Islands), in present-day British Columbia, that “Slaves sometimes regain their freedom by running away, but should they return to their native place they are generally so much despised that their lives are rendered miserable.”

The life of any slave was tenuous, and slaves lived and died at the mercy and whims of their masters. Slaves could be severely punished or killed for any reason, as the following account, by an Eyak individual named Galushia transcribed by Kaj Birket-Smith, illustrates:

“A party of Yakutat Tlingit were on a journey. They had not killed anything for a long time and were very hungry. Finally they secured some game and cooked it. One man had a slave with him but refused to give him any food. When they were ready to leave their camping place, the slave was picking the bones. The master beat him to death because he had kept the boats waiting.”

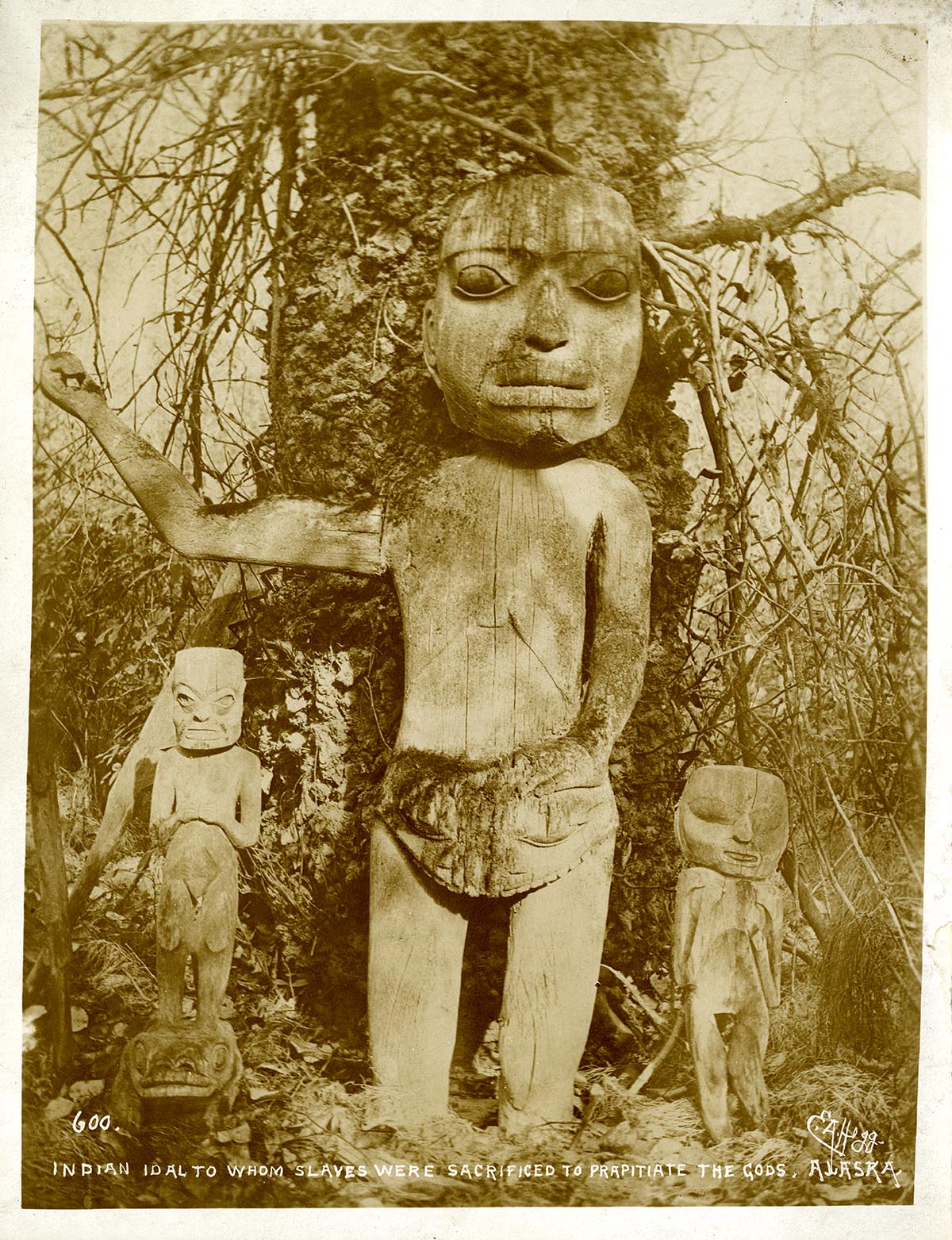

In addition to punitive killings, slaves faced the threat of death in rituals and ceremonies. The destruction of property was a central concept in Northwest Coast societies, and slaves, like other forms of property, could be destroyed in a wide variety of ritual events. In some cases, the value of a slave could be “destroyed” by setting the slave free, but in other cases slaves were simply killed. In “Social Structure and Social Life of the Tlingit,” R.L. Olson reports on an instance in which the destruction of a slave played a role in asserting ownership of a salmon stream on Prince of Wales Island:

“The creek in Kegan Cove called wásga’t was discovered by Giswe’h of Kats’ House Tekwedih. The title finally went to Gantcuh, GM’s father who had slaves rebuild the weir each spring and at each rebuilding a slave was either freed or killed to validate the claim.”

Slaves could be killed in conjunction with celebrations, conflict resolutions, or many other events, but the two most perilous ritual events for a slave were likely funerals and potlaches. At funerals for important high-status individuals, slaves were often killed to demonstrate the worth of their masters and to accompany the master in the afterlife. At potlaches, large numbers of slaves could be killed in a single event:

“Shakes was having his children’s ears pierced and it was quite common that slaves be killed during the ceremonies. This ‘chief’ of the slaves boasted that his master could do nothing to him. But Shakes heard of this and had him beheaded in the course of the festival.”

Another story recounted by Olson, also involving Chief Shakes, demonstrates how even the life of a favored slave could hang in precarious balance:

“The Nanyaayih chiefs had the reputation of having many slaves killed at their potlatches. Old Shakes had a female slave of whom he was very fond. The other dancers used to trick him by tossing this slave to him, to be thrown out the door to be killed. But he always tossed her back.”

Sources differ about the treatment of the bodies of slaves, but the most common approach seems to have been to cast them out of the community into the woods or the ocean. In “Contributions to the Ethnology of the Haida,” published in 1905, John Swanton writes that “the bodies of slaves were thrown into the sea, for otherwise the owner thought he would never acquire more property.” The anthropologist Leland Donald speculates that this practice may have been connected to the ritual return of salmon parts to the ocean by the Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, and other groups in present-day Alaska, which were intended to ensure strong future salmon runs.

III.

Turning of the Tides

The arrival of Europeans and Americans starting in the late 1700s upended centuries of social, economic, and political order in present-day Southeast Alaska. A flood of Western goods and demand for furs disrupted local economies and trade networks. Diseases such as typhoid, influenza, leprosy, and whooping cough devastated indigenous communities. The smallpox epidemic of 1835-1838 alone may have killed more than a third of Tlingit, Haida, and other Northwest Coast populations, including half of the indigenous residents of Sitka. Throughout the 1800s, Western missionaries, teachers, traders, and civil and military authorities increasingly asserted the supremacy of Western beliefs and institutions at the expense of indigenous customs and ways of life.

The Western reaction to indigenous slavery in present-day Alaska was complicated, reflecting a great variety of self-interests and a general lack of centralized government authority. Russian captains purchased slaves from the Yakutat Tlingit on several occasions in the eighteenth and early nineteen centuries, and American captains occasionally transported, captured, or sold slaves while trading up the Northwest Coast. In many Northwest Coast communities, indigenous slaveholders put female slaves to work as prostitutes for Western crews, in some instances causing the value of female slaves to equal or exceed that of males.

The fur trade created a regional economic boom that peaked in the middle of the nineteenth century and, at least in some locations, became deeply entangled with the slave trade. In 1840, an employee of the Hudson Bay Company named James Douglas described his frustration attempting to operate in a marketplace that also included slaves:

“The species of property most highly prized among [the Taku Tlingit] is that of slaves, which in fact constitutes their measure of wealth… [S]laves being through this national perversion of sentiment, the most saleable commodity here, the native pedlars, come from as far south as [Kaigani Haida] with their human assortments and readily obtain from 18 to 20 skins a head for them. The greater number of these slaves are captives made in war, and many predatory excursions are undertaken not to avenge international aggressions, but simply with a sordid view to the profits that may arise from the sale of the captives taken…

A few days ago a canoe from [Kaigani Haida] brought in four slaves, and a second from [Stikine Tlingit] brought one which were immediately purchased at the prices stated above.”

Though most Western nations practiced slavery during the 1700s, during the 1800s Western sentiment began to turn against the institution. Britain outlawed participation in the slave trade in 1807, and in 1833, the Slavery Abolition Act established the end of slavery in the British Empire. The Emancipation Reform of 1861 ended private serfdom throughout Russia, freeing nearly four in ten Russians from slave-like conditions. The United States prohibited the international importation of slaves in 1808, and hereditary chattel slavery ended in the contiguous United States in the mid-1860s following the bloody American Civil War.

Indigenous slavery on the Northwest Coast was not considered a political priority by Western powers, but this shift in attitudes clearly affected cross-cultural interactions in the region. Russian, American, and British individuals generally refused to assist in the capture or return of runaway slaves, and on repeated occasions encouraged or paid indigenous slaveholders to release slaves rather than kill them in ceremonies. Moreover, Western powers forcibly suppressed slave raids and other intergroup conflicts that could imperil regional stability or disrupt Western commerce. While surveying Russian Alaska in 1862, Captain P.N. Golovin commented on Russian efforts to curtail slave killings by the Tlingit:

“Usually all the toions [chiefs] have slaves who are called kalgas. A kalga is the property of his owner and can be disposed of at will; he is considered a chattel, not a human being. During certain ceremonies and special occasions it is the custom to kill kalgas. For example, when a toion dies one or two of his kalgas are killed so that the toion will have the service he needs in his next life. This kind of killing is no longer done on Sitka. The Chief Managers have been working at this constantly, and have finally succeeded in persuading the toions that instead of killing a kalga they should sell him to the Company or free him. But if the killing is no longer in vogue next to the walls of the fortress in view of the Russians, this does not mean that this barbaric custom has been completely abandoned by the Sitka [Tlinglit]. They say with total assurance that whenever a toion wants to kill a kalga he takes him to one of the settlements of a friendly tribe and kills him there in accordance with custom.”

Nevertheless, while slavery almost certainly decreased during the nineteenth century, numerous sources affirm that slavery was openly practiced and was not unusual. Similarly, while the killing of slaves also decreased during this time period, there is ample evidence that the custom persisted. Perhaps the latest historical account of a slave killing was written by missionary Hall Young, who had attempted–likely without success–to free several slaves held by the Stikine Tlingit in 1878. Hall’s autobiography includes a secondhand account of a ritual killing witnessed by a young Haida girl he called Susie in (or just prior to) 1880:

“Not very long before her arrival at Fort Wrangell she had gone through a terrible experience. There were three little girls in the family, Susie being the middle one. They had an old slave who was more of a father to the little girls than their own parent. The old slave used to carry them on his back across the streams, make toys for them and give them little beads which looked like pearls. These were made from small pods of fucus or transparent seaweed; the old man filled them full of white venison tallow, and they made very beautiful, pearl-like beads.”

According to Young, Susie’s father, a high-status chief and renowned woodworker named Kenowan, died of consumption despite the best efforts of the local healers. At Kenowan’s funeral feast, Susie and her sisters were compelled to watch as the old slave was laid on the ground next to Kenowan’s body and killed with a greenstone ax.

IV.

A Thing Which it is Not

The United States purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867. But from 1867 through 1884, there were no courthouses, civil police, or tools to make or enforce law in the newly-acquired territory. Rather, the “Department of Alaska” was haphazardly administered, in sequence, by the U.S. Army, U.S. Treasury, and the U.S. Navy. The 1880 Census Report described Alaska’s political organization–or lack thereof–as follows:

“Alaska is now, and has been since its acquisition by the United States, ‘a thing which it is not,’ a territory in name only, without its organization. It is a customs district, for the collection of customs only, with a collector and three deputies separated by hundreds or even thousands of miles. It has no laws but a few treasury regulations, with no county or other subdivisions, and, of course, no capital. The collector of customs and the only representatives of police restrictions–a man-of-war with its commander–are located at Sitka, cut off from all communication with the bulk of the territory except by way of San Francisco.”

Despite its absentee governance in Alaska as a whole, reports to Congress suggest that the U.S. Navy did preoccupy itself with several tasks in Sitka and the vicinity: establishing schools, enforcing alcohol prohibition, and attempting to maintain the fragile peace between whites and indigenous populations. The gradual assertion of American power caused friction between indigenous and American communities, and occasionally spilled over into conflict.

In 1879, the USS Jamestown arrived at Sitka following claims—likely exaggerated—that the white residents of Sitka feared an attack by the Tlingit. The Jamestown was a sloop-of-war with a notable record of service in the U.S. Civil War, where she had captured or destroyed the Confederate vessels Alvardeo, Aigburth, Colonel Long, and Intended before sailing for the Pacific to hunt Confederate privateers.

In a report to the Secretary of the Navy detailing his June 1879 to September 1880 tenure on the Jamestown, Commander L.A. Beardslee makes occasional mention of slavery, noting that “slaves, furs, or blankets” could be used to pay debts and that the ownership of slaves conferred social status on their owners. In one passage, Beardslee notes, with apparent satisfaction, that a Chilkat chief had not only opened an area to prospecting by white miners but had also furnished the miners with slaves. Beardslee’s report only directly addresses slavery once and seems to view the subject with ambivalence, acknowledging its impropriety while also suggesting that disrupting indigenous power structures could harm American interests:

“There is another custom among them against which I could make no headway, and therefore did not try, viz: that of owning slaves, which is quite common. As the possession of the slaves gave much importance to the owners–an importance which it was thought best to foster–this problem was for civil law to solve.”

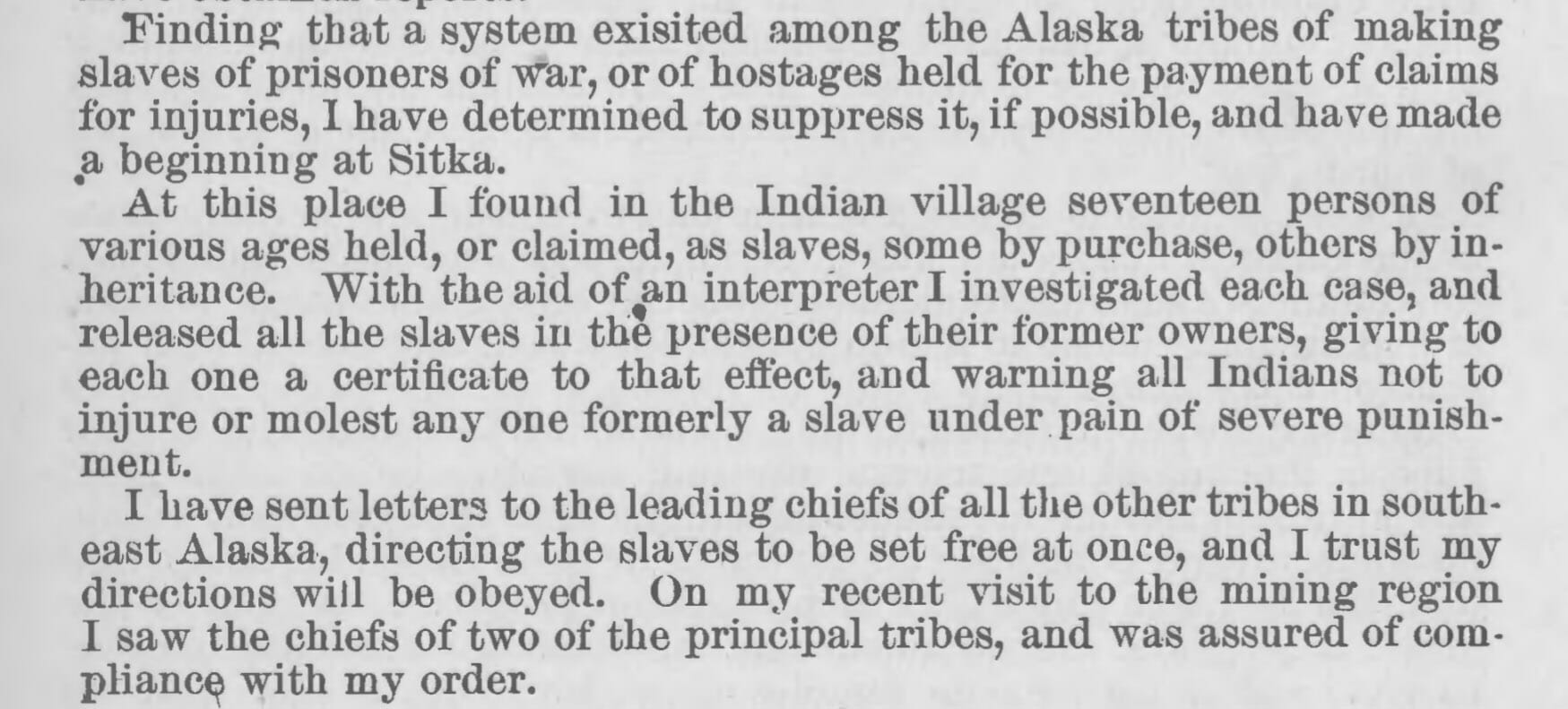

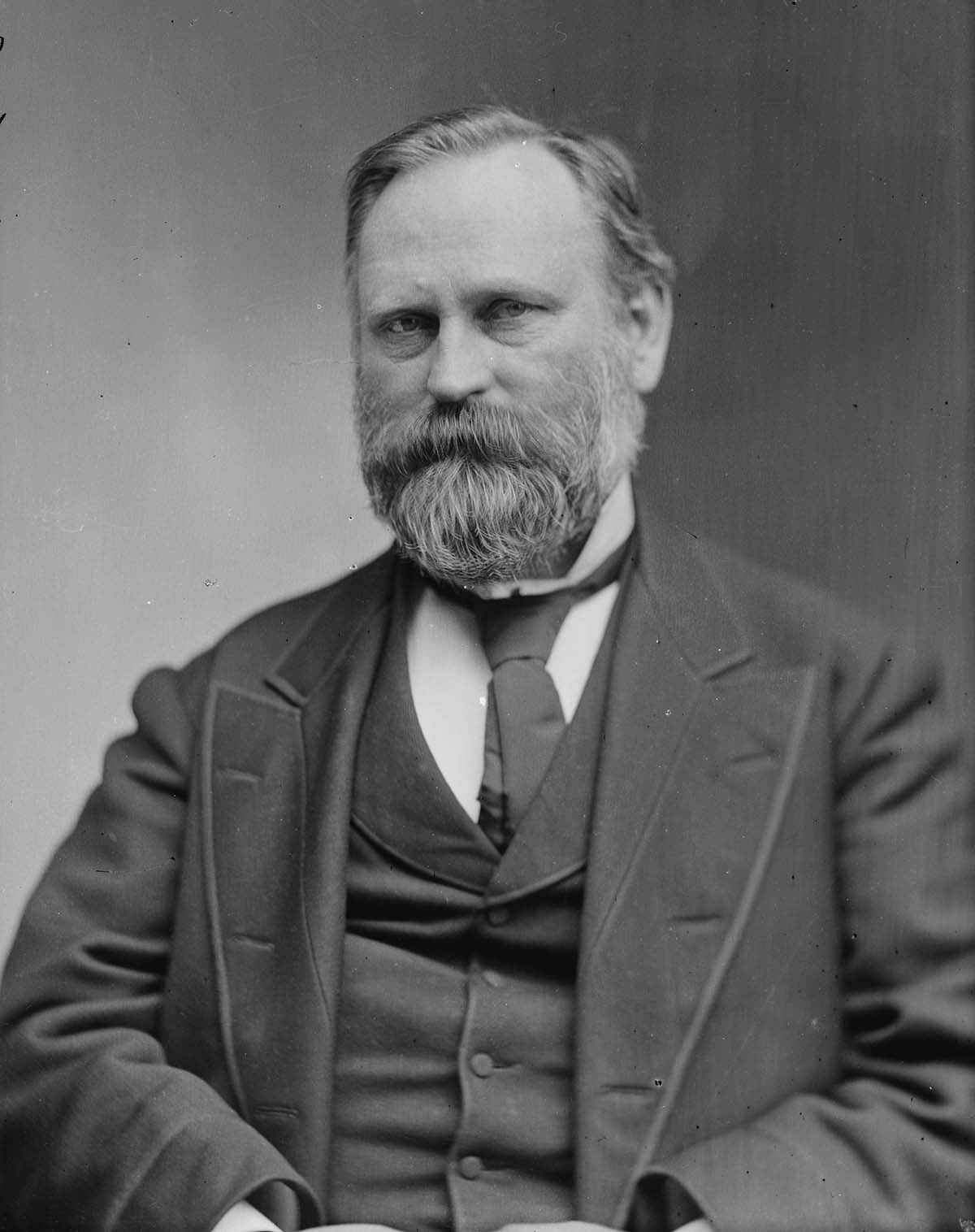

In September 1880, Beardslee turned command of the Jamestown over to Admiral Henry Glass, a distinguished Union Civil War veteran who had participated in the capture of Confederate Georgetown, South Carolina. Glass’ reports to the Secretary of the Navy reflect a particular determination to disrupt the production and distribution of “Hoo-chee-hoo,” a distilled spirit so notorious that the word “hooch” permanently entered the American vernacular as slang for noxious or illegal liquor. But in the spring of 1881, Glass appears to have turned his attention, if briefly, to another task: freeing slaves. In his May 9, 1881 report to the Secretary of the Navy, reproduced in a report to the U.S. Congress, Glass writes that he freed seventeen slaves in Sitka and ordered other Southeast tribal leaders to free their slaves as well:

It is unclear whether Glass took further actions to free Alaska slaves, and neither he nor the Jamestown remained in Alaska for long. On July 30, 1881, the USS Wachusett arrived in Sitka and shortly thereafter the Jamestown headed south to San Francisco, where she was decommissioned in September of that year. She was recommissioned as a training and hospital ship, and eventually destroyed in a fire at the Norfolk Navy Yard on January 3, 1913.

It remains a strange historical irony that the Jamestown, named after the Virginia colony where African slaves were first brought to mainland British North America in 1619, was involved both in ending slavery in the American South and freeing what may have been the last group of enslaved people of its size in North America.

V.

The District of Alaska

Congress passed the Organic Act in 1884, abolishing the “Department of Alaska” and replacing it with the “District of Alaska.” (Alaska would not reach territorial status until 1912.) The Organic Act supplied Alaska with its first civil bureaucracy, which included a presidentially appointed governor, U.S. attorney, marshal, clerk of court, and federal judge. The judge was to hold court in Sitka from May through November and in Wrangell for the remainder of the year, applying the civil and criminal laws of the State of Oregon to the newly minted District.

In December 1885, President Grover Cleveland appointed Missouri attorney Lafayette Dawson to replace the former District Judge, Edward J. Dawne, who had obtained the judgeship despite a colorful past. Dawne had been fired from a medical professorship in Oregon after it was discovered he had no training in medicine, and was dismissed from his next position as a preacher of a Methodist church for unknown reasons. Dawne had gone missing after departing Sitka in a canoe to hold court in Wrangell. Alaska Governor Alfred P. Swineford reported to Attorney General Augustus Hill Garland that Dawne “is missing, with every evidence of having fled the district to evade threatened arrest on charges of forgery and embezzlement.” Dawne’s wife later confirmed these accusations and stated that she believed he had fled to British Columbia. Three days after President Cleveland received news of Dawne’s disappearance, he appointed Lafayette Dawson to the newly-vacated judgeship. Dawne’s wife later field for divorce. He was never seen again.

Dawson was to serve from 1886 through 1888. In Sitka, he joined U.S. Attorney Mottrom Dulany (M.D.) Ball, a former member of the Confederate cavalry. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Ball appears to have accepted the Confederacy’s defeat in the Civil War. He had publicly praised the ability to shake the hands of northerners again, and claimed to now look upon the “stars and stripes” as an emblem of freedom. From 1878 to 1879, Ball had served as the Collector of U.S. Customs during the years when the Treasury oversaw the Department of Alaska, making the former confederate cavalryman the most powerful United States authority in Alaska.

Shortly after taking office, Dawson received a remarkable petition from a Sitka attorney named Willoughby Clark. Clark’s petition was filed on behalf of an individual named Sah Quah, and alleged that, in clear violation of U.S. law, Sah Quah was held as “slave and chattel” of an individual resident of Sitka named Nah-Ki-Klan. On April 19, 1886, Dawson granted the petition, which directed the U.S. Marshal to serve Nah-Ki-Klan with an order commanding the production of Sah Quah to the court for a hearing. The U.S. Marshal, Barton Atrius, completed service of the order on Nah-Ki-Klan the next day, April 20.

At the hearing, which was set for April 26, the court would be required to determine whether a Sitka man was being held as a slave. And if so, Judge Dawson would have to answer an extraordinary question: was slavery legal in Alaska as long as it was practiced between Alaska Natives?

VI.

Slave Trial in Sitka

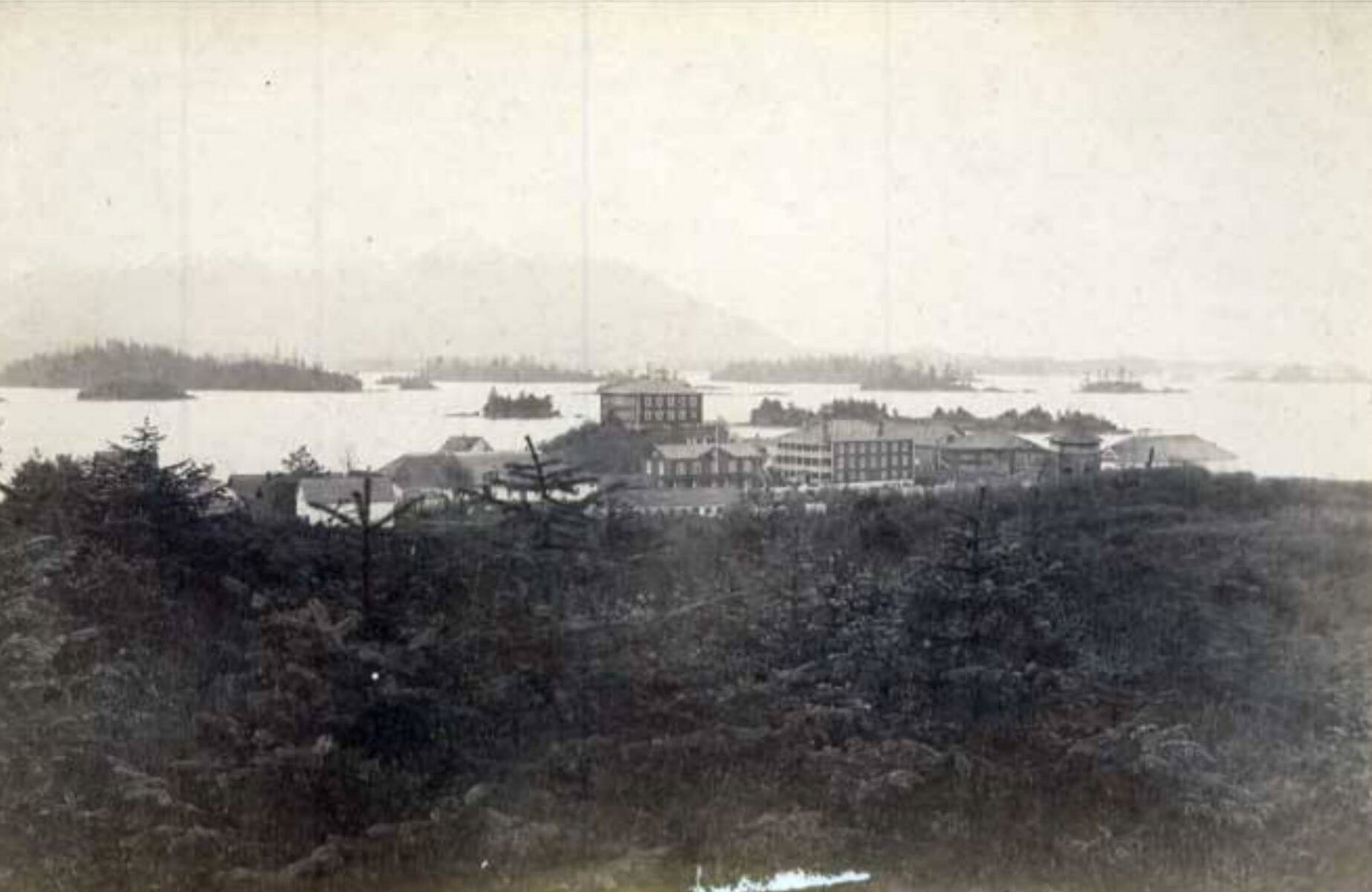

Present-day Sitka is a seaside town of about 8,500 residents, known for its temperate coastal scenery, fishing, and tourism. But in the 1880s, Sitka was the largest city in Alaska and seat of American power. No other location better epitomized the cultural clashes and shifting of political balance in Alaska during the nineteenth century. The name Sitka is an Anglicized contraction of the Tlingit phrase Shee At’iká, meaning “People on the Outside of Baranof Island (Sheet’-ká X’áat’l).” In 1775, the Spanish ship Sonora, led by Peruvian naval officer Bodega y Quadra, headed north to assess potential Russian settlement and enforce Spanish colonial claims. Quadra reached the vicinity of Sitka, naming an elegant volcano across from the modern city site “Montaña de San Jacinto.” In 1778, the peak was named “Mount Edgecumbe” by English explorer Captain Cook.

In 1799, Russian settlers established Fort of Archangel Michael in Old Sitka, but Tlingit warriors attacked the fort in 1802 and killed nearly all of its Russian and Aleut inhabitants. In 1804, the Governor of Russian America, Alexander Baranov, assembled a force of hundreds of Russians and Aleuts and retook the fort after a series of chaotic and bloody engagements with the Tlingit known as the “Battle of Sitka.” Sitka became the Capitol of Russian Alaska in 1808, and was the site of the ceremonial transfer of Alaska from Russian to American ownership in 1867. By that time it had grown into a rugged but prosperous city inhabited by Russians and other Europeans, Americans, and indigenous peoples, the latter of whom lived in an area called the Ranch, or Indian Town. Court documents claim that Sah Quah and Na-Ki-Klan had resided in this part of Sitka.

The trial was held in a military barracks that had been partially repurposed for use by the court. Willoughby Clark, the attorney who had brought the petition to Judge Dawson, represented Sah Quah. Dawson appointed M.D. Ball, the U.S. Attorney for Alaska, to represent Na-Ki-Klan, who was not present. Judge Lafayette Dawson presided.

Sah Quah trial transcript

The Landmine obtained a copy of the original trial transcript from the Alaska State Archives in Juneau and commissioned a digital transcription. We believe this may be the only transcription of the full case available to the public. The digital transcription may be updated as resources allow.

According to the transcript, Willoughby Clark began by asking Sah Quah about the circumstances surrounding his enslavement as a child.

Willoughby Clark: When did you leave there [living with the Haida]?

Sah Quah: I don’t know, but a long time ago a great many years ago. I was stolen when I was a little boy by the Flat Heade.

WC: Where did they take you?

SQ: To [unreadable] in British Columbia, a river below the Skeena River.

WC: What did they do with you there?

SQ: The made a slave of me. They took me to the Stikine River a portion of that is not in Alaska.

Next, Clark asked Sah Quah to describe the sequence of events that had brought him to Sitka. Sah Quah described a life of periodic upheaval, as he was trafficked up the Northwest Coast to a series of masters in Stikine, Cihhlkat, and Yakutat.

Willoughby Clark: What did they do with you at the Stikine River; hold you as a slave?

Sah Quah: Yes.

WC: Was it the same master?

SQ: Another man

WC: At the Stikine River you were held by another man where did you go from there?

SQ: Chilcat

WC: Same master?

SQ: Another

WC: How did you happen to change masters were you sold?

SQ: Yes.

WC: Where were you sold to next?

SQ: Yakutat

WC: It near the mouth of St. Elias in Behringe Bay?

SQ: Yes sir

WC: Where did you go from there?

SQ: That is all.

At this point, the trial took an unexpected turn when Sah Quah described his current master, a Tlingit man named Na-Ki-Klan, as his father.

Willoughby Clark: Are you the slave of this man [Na-Ki-Klan]?

Sah Quah: He is my father.

WC: Is he your master also?

SQ: Yes, he is my father.

WC: What do you mean by that is he really your father?

SQ: Yes sir.

Willoughby Clark, clearly surprised by Sah Quah’s claim that Na-Ki-Klan was in fact his father, pushed Sah Quah to explain himself. But not only did Sah Quah maintain that he was Na-Ki-Klan’s son, he added that Na-Ki-Klan and his prior masters had treated him well.

Willoughby Clark: Do you swear this man treats you as a father you consider yourself a son?

Sah Quah: Yes sir

WC: Have you considered yourself a slave of this man ever since you left Yakutat?

SQ: No

WC: You need not be afraid. No one will hurt you. Tell it just as you told us.

SQ: He is just like my father.

Court: Mr. Clark, I think that inquiry unnecessary as slavery is admitted.

WC: I have to make it to know if he should be released but it is unnecessary.

WC: Have you always been treated well by this man or have any of them ever abused you?

SQ: No.

WC: None ever abused you?

SQ: No.

Willoughby Clark asked Sah Quah whether his eye had been put out intentionally, but Sah Quah explained that he had lost it while hunting bear. Clark then asked Sah Quah whether he had been paid for his labor, and about any prior attempt by Sah Quah to seek freedom from enslavement.

WC: Has your master ever paid you?

SQ: No.

WC: Did you ever make any application before to get free?

SQ: No.

WC: Have you had any conversations with your master or any other Indian in regard to their trial, did they threaten you or tell you what to say? Now you must tell the truth.

SQ: No.

Clark, now clearly frustrated by his client, reminded Sah Quah how these proceedings had come about. Clark finally received the answers needed to proceed with the trial.

Willoughby Clark: When I sent you from my office to make a demand and for your freedom did you do so?

Sah Quah: Yes, I told you I was a slave and I wanted a paper from the big chief so I could walk around like any other man.

Court: Do you want that now?

SQ: I like to be here now and sit here and like to get [indecipherable] and be my own master.

WC: Did you ask your master for freedom when I sent you down?

SQ: Yes. When I asked this man I did not know that he was going to give me freedom. When I asked him he informed me he was going to give me freedom in the fall of the year.

WC: After he had finished building the house hew as to leave you.

On cross-examination by U.S. District Attorney M.D. Ball, Sah Quah confirmed that he had seen other slaves when he was held by the Chilcats, and when he was in Yakutat. Sah Quah also confirmed that the person he called his father had paid for him, but was adamant that he had lost his eye in a natural event and it was not a mark inflicted on him.

Clark then called a Tlingit woman named Marchia who resided in Sitka. She was uncomfortable testifying, stating she was “bashful.” Marchia confirmed she had been a slave of another woman starting when she was “a little girl,” but had been free for roughly the last two years.

The final witness was a local man named Annahootz. Annahootz was a clan leader among Sitka Tlingits who had been recruited by the U.S. Navy to serve as a policeman and intermediary between the Navy and the Tlingit community. Annahootz first answered several questions about Tlingit social structure, stating that chiefs ruled only over their own families and not over a broader tribal group. Next, the questioning turned to slavery. Annahootz stated that indigenous groups had once been in a state of “constant war” and that slaves had been taken in conflict or to pay debts, but that slavery was not hereditary and was no longer practiced. Finally, Annahootz explained Sah Quah’s claim that his master was his father, stating that “[Sah Quah] told the truth when he called his owner father when a slave loses a parent he calls his owner father.”

According to the Sitka newspaper The Alaskan (which was founded by M.D. Ball), Major M.P. Berry, who served as Willoughby Clark’s co-counsel for Sah Quah, then recounted several harrowing accounts of Alaska slave killings to the court. First, Berry described a report by a Lieutenant Dyer that he and several other troops had saved a female slave in 1874 or 1875 at Fort Wrangel. The slave had been “bound and gagged and thrown where the incoming tide would end her miserable existence.” Dyer and his companions, Berry said, had rescued the woman despite loud protest by slaveholders, but were unable to rescue two men, whose drowned bodies “drifted back and forth, the sport of the waters.”

Next, Berry recounted a story by a prospector who claimed to have seen several slaves killed during funeral rites for a medicine man. According to Berry, the prospector had been exploring the headwaters of the Chilkoot Inlet when he came across a village and saw three starved slaves “naked, bound and staked to the ground.” The prospector, who recognized two of the slaves from Sitka, reported that he had tried negotiate their release had been unsuccessful. “I offered all that I had and dealt liberally in promises,” the prospector had said, according to Berry, but “the fate of the slaves was sealed. They were consigned to torture and a lingering death. I then thought it was my duty to shoot them and made up my mind to do so. To conclude I did just nothing, being glad to escape myself.”

M.D. Ball’s arguments on behalf of Na-Ki-Klan seem to have been brief. Ball stated that he had initially believed the Thirteenth Amendment to apply to all persons living in American territory, but that research had led him to believe that its provisions only applied to American citizens:

The United States has never, by any exercise of its authority, shown that its great edict of liberty was intended to apply to Alaska any more than that of Russia did. The amendment must be taken in the sense in which it was intended to operate at the time of its adoption, and I have not been able to find that any exercise of the law-making power which is provided in it for giving it effect, was ever brought to bear upon Indians living under their own laws and costumes in tribal communities.

VII.

Crow Dog

An 1883 case and its aftermath would feature prominently in Dawson’s decision in In re Sah Quah. On August 5, 1881, on the Great Sioux Reservation in present-day South Dakota, a Brulé Lakota subchief named Crow Dog shot and killed Lakota chief Spotted Tail. The killing was addressed according to Sioux law, and Crow Dog was ordered to resolve the matter by paying $600, eight horses, and one blanket in restitution to Spotted Tail’s family. However, the high-profile killing of the Lakota chief angered American authorities, who considered Spotted Tail a moderating influence during a particularly fraught time for American and Indian relations. Crow Dog was arrested and tried for murder under the laws of the Dakota Territory. On May 11, 1882, he was convicted and sentenced to hang.

Crow Dog appealed the decision to the territorial Supreme Court, and the federal government paid Crow Dog’s appeal to the United States Supreme Court. In a unanimous decision on December 17, 1883, the U.S. Supreme Court declared in Ex Parte Crow Dog that Crow Dog’s conviction and sentence “are void, and that his imprisonment is illegal.” Writing for the Majority, Justice Stanley Matthews noted that nearly a century of American legal precedent had established that offenses committed between Native Americans in “Indian Country” were to be adjudicated solely by the tribes and not by U.S. courts, and that there was no legal basis for a departure from this standard. To apply American legal authority to crimes between Indians in Indian Country, Matthews wrote, would require “a clear expression of the intention of Congress, and that we have not been able to find.”

As it turned out, Congress was more than willing to furnish this “expression,” and passed the Major Crimes Act in 1885. For the first time, the Act gave the federal government jurisdiction over specific crimes committed between Native Americans in “Indian Country”:

§ 9. That immediately upon and after the date of the passage of this act, all Indians committing against the person or property of another Indian or other person any of the following crimes, namely, murder, manslaughter, rape, assault with intent to kill, arson, burglary, and larceny, within any territory of the United States, and either within or without the Indian reservation, shall be subject therefor to the laws of said territory relating to said crimes, and shall be tried therefor in the same courts, and in the same manner, and shall be subject to the same penalties, as are all other persons charged with the commission of the said crimes respectively;…

Since the founding of the United States, it had been both law and policy to recognize Native American groups as sovereign entities. This position was established in the Constitution of the United States, and had been affirmed by over a century of court decisions, legislation, and treaties between American and Native entities. But in the latter half of the nineteenth century, America’s westward expansion, increasing national identity, and growing desire to control and assimilate Native populations put American jurisprudence in a collision course with Native American sovereignty and tribal law.

In 1871, The Indian Appropriations Act barred the United States from recognizing the independence of any additional “Indian nation or tribe,” and forbade the U.S. from signing new treaties with indigenous groups. The formation of the United States Indian Police Force (USIP) in 1879-80 represented a concerted effort to bring federal law enforcement into Native-controlled lands. The Major Crimes Act of 1885, passed in direct response to Ex parte Crow Dog, forcefully asserted the supremacy of American federal law, even in conflicts between Native individuals in Native American lands.

This erosion of tribal sovereignty and claim that American law trumped indigenous law and custom served as the backdrop for In re Sah Quah. To the extent that this was a period of legal chaos for the field of indigenous law in the contiguous United States, this chaos was multiplied in Alaska. Two decades of haphazard federal rule had left Alaska with a confusing and often contradictory set of court and law enforcement precedents, riddled with unresolved questions. Were Alaska Native groups tribes? Was Alaska Indian Country? Were Alaska Native tribes sovereigns? If so, could that sovereignty permit the ownership of slaves?

In deciding In re Sah Quah–just a year after the passage of the Major Crimes Act–Judge Dawson attempted provide answers to these questions. In doing so, he would not only decide the fate of one enslaved man, but would attempt to establish a legal framework that would guide the future of Alaska.

VIII.

May 8, 1886

Twelve days after the hearing, Judge Dawson issued the court’s decision in In re Sah Quah. In his decision, Dawson briefly summarizes the facts of the case and the arguments made by Ball on behalf of Na-Ki-Klan before setting forth a series of arguments for the absolute supremacy of American law in all Alaska legal matters.

Dawson noted that the treaty between Russia and the United States transferring ownership of Alaska had granted all power of law to the United States and none to the tribes. This, according to Dawson, suggested that indigenous groups were “even then regarded as subject to some power superior to their own.” Next, Dawson turned to the subject of Alaska’s status as Indian Country. Dawson acknowledged that aspects of Indian Country law had occasionally been applied to Alaska, but argued that the limited application of these laws meant that Alaska had never been intended to be “Indian Country” in a formal legal sense. According to Dawson, Alaska Natives were already assimilating into American life, rendering questions of sovereignty increasingly moot:

“What then is the legal status of Alaska Indians? Many of them have connected themselves with the mission churches manifest a great interest in the education of their youth and have adopted civilized habits of life. Their condition has been gradually changing until the attributes of their original sovereignty have been lost and they are becoming more and more dependent upon and subject to the laws of the United States and yet they are not citizens within the full meaning of that term.

Dawson recognized the long history of tribal independence and sovereignty in American law, citing Ex parte Crow Dog, and took pains to explain why Alaska Native groups did not warrant the same sovereignty accorded groups in the contiguous United States. Namely, Dawson wrote, the United States had neither recognized nor signed any treaty with any Native entity in Alaska, and Alaska’s indigenous societies lacked the political organization that would have permitted tribal recognition in the first place. Dawson concluded that Alaska Natives were subjects of the American government, without the powers of sovereignty that would permit them to enact or uphold a system of slavery contrary to American law:

“The doctrine enunciated by the supreme court of the United States in the Crow Dog Case, (1883,) 109 U. S. 556, 3 Sup. Ct. Rep. 396, is based upon the idea of the supremacy and independence of the Brule Sioux tribe of Indians, in their tribal capacity, as admitted and recognized by the United States in a treaty stipulation. It was held that the district court of Dakota had no jurisdiction to try and punish Crow Dog for the murder of a member of his own race, because he had been or was liable to be punished by the local law of the tribe. But does the rule in that case apply to the Indians of Alaska? I think not, and for various reasons. The United States has at no time recognized any tribal independence or relations among these Indians, has never treated with them in any capacity, but from every act of congress in relation to the people of this territory it is clearly inferable that they have been and now are regarded as dependent subjects, amenable to the penal laws of the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction of its courts. Upon a careful examination of the habits of these natives, of their modes of living, and their traditions, I am inclined to the opinion that their system is essentially patriarchal, and not tribal, as we understand that term in its application to other Indians. They are practically in a state of pupilage, and sustain a relation to the United States similar to that of a ward to a guardian, and have no such independence or supremacy as will permit them to sustain and enforce a system of forced servitude at variance with the fundamental laws of the United States.”

Finally, Dawson issued his verdict:

“The petitioner testifies that he was captured and sold into slavery when a mere boy; that his labor from that time to this has been appropriated by others. He has lost one eye, his ears are badly mutilated, and he is certainly a sad spectacle of humiliated manhood. The crack of the lash, the torture of mutilation, the fear of death, the annoyance of the juggler, the excess of manual labor imposed upon him, the extreme hardships of his life, with the sense of degradation and inferiority constantly before him, have subdued his manhood, and the pitiable spectacle of his once stately form is an evidence of the blighting curse of slavery. This case has been ably argued on both sides, and all the learning accessible to the attorneys has been brought to bear but I can arrive at no other conclusion than that the petitioner must be released from the merciless restraint imposed upon him, and go forth a free man, and such is the order of the court.”

On May 8, 1886, Dawson ruled that slavery was illegal between all persons in Alaska. Sah Quah would walk out of the courtroom a free man.

IX.

Test case?

Contemporary historians and legal writers have not been kind to In re Sah Quah. Critics frequently allege that those involved in the case were motivated not by the plight of an individual slave or a wish to end Alaska slavery generally, but by a desire to impugn Tlingit culture and establish a legal framework to justify infringement of Alaska Native sovereignty. A 2020 U.S. Supreme Court decision regarding whether Alaska Native Corporations were eligible for federal Covid relief funds earmarked for tribes, for example, describes In re Sah Quah as an early example of jurisprudence that attempted to limit sovereignty.

In the 1989 CUNY Law Review, Sidney Harring provides a representative critique of In re Sah Quah:

While doctrinally not a significant case, Sah Quah represented a major White intrusion into Tlingit society, revealing a great deal about both Tlingit and White relations in Sitka and about the changing internal dynamics of Tlingit society in the face of the extension of White authority over their people.

Ex parte Sah Quah made it clear that Americans in Alaska were deeply involved in a struggle to destroy Tlingit society and assimilate its people as useful citizens of the White community of Alaska.

Critics cite Sah Quah’s confusing and at times contradictory testimony, arguing that by the 1880s slaves were well-treated and enslavement was of minimal social importance. Critics also focus on Judge Dawson’s incomplete or flawed conclusions about Alaska Native culture and social organization.

Dawson’s claim that Alaska Natives were already steadily assimilating into white society was, at most, only true in a limited way and only in a small geographic portion of the District. The 1890 U.S. Census reports a white population in Alaska of just over 4,000, and this population was concentrated almost entirely in a few settlements along the Pacific coast. It would have come as news to Native groups in many parts of Alaska that they were already assimilating into a culture with which they had had virtually no contact.

More problematic to critics are Dawson’s arguments regarding the structure of Tlingit society, the evidence for sovereignty among Alaska Native groups, and the status of Alaska as Indian Country. First, Dawson’s conclusion that the Tlingit (and, by extension, other Alaska Native groups) were “patriarchal, and not tribal” ignores the deep interwovenness of Tlingit social organization. Tlingit groups were united by language, culture, religion, a highly codified system of relationships between groups and subgroups, and a complex system of inter and intra-group law and governance. And while the Tlingits as a whole may have lacked the formalities of Western executive heirarchy, groups were able to unite in common purpose and did so frequently.

Dawson’s arguments about sovereignty can be viewed as similarly myopic. Though true that Congress had never entered into any treaties with Alaska Native entities, agents of the federal government had frequently negotiated and crafted agreements with Alaska Native groups on a variety of subjects typically negotiated between sovereigns, including access to lands, enforcement of different legal systems, and import/export of trade goods. In numerous cases, agents of the federal government had recognized and enforced elements of tribal law. While these could be framed as pragmatic actions taken by federal agents to keep the peace, it could also be argued that this reflected an obvious reality: that Alaska Native groups, and not the federal government, maintained unilateral control over broad swaths of Alaska.

Dawson’s conclusion that Alaska was not Indian Country, therefore, was dismissive of facts on the ground and relied on circular legal reasoning: Tribes are only tribes if they are recognized by the federal government, but the federal government cannot and should not recognize Alaska Native groups as tribes, therefore they are not tribes. The question of whether Alaska Native groups were sovereign was answered, at least in In re Sah Quah, at a time when the legal system itself permitted no answer except “no.”

Nevertheless, while critics are correct to criticize Dawson’s statements about Tlingit culture, they often commit errors of their own. Some attempt to discredit Sah Quah himself by highlighting the contradictions in his testimony. At least one critic has even suggested that Na-Ki-Klan may actually have been Sah Quah’s father, ignoring Annahootz’ testimony that slaves often refer to their masters by that name. Though the inconsistencies in Sah Quah’s testimony are certainly notable, they are not surprising given the language and cultural barriers. Sah Quah’s testimony about his history of enslavement and his current status as a slave—which, he explained, would end after he built a house for Na-Ki-Klan for no pay—was consistent with the historical picture of Northwest Coast slavery in the nineteenth century.

More disturbingly, critics of the case often downplay or disregard the horrors of enslavement itself. As Harring writes:

The institution was based on Tlingit family hierarchies of wealth and power and was rooted in a long tradition of raiding neighboring villages. Slaves seized in these raids were loosely incorporated into Tlingit families. Although slavery was quite extensive among these peoples in the early 1800s, in some estimates amounting to thirty percent of the total population, it was dying out by the end of the century.

For those remaining slaves, it was not even clear that being a slave had much meaning. Rather, the slaves functioned as adopted members of families who could not easily be turned away.

Readers might be surprised to find contemporary legal scholars minimizing the horrors of slavery, but the compulsion to treat slavery practiced by ones own group–or, perhaps, a group that one views favorably–as benign is a remarkably universal moral failing. As the Abolitionist Theodore Weld told the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839:

Slaveholders talk of treating men well, and yet not only rob them of all they get, and as fast as they get it, but rob them of themselves, also; their very hands and feet, all their muscles, and limbs, and senses, their bodies and minds, their time and liberty and earnings, their free speech and rights of conscience, their right to acquire knowledge, and property, and reputation;—and yet they, who plunder them of all these, would fain make us believe that their soft hearts ooze out so lovingly toward their slaves that they always keep them well housed and well clad, never push them too hard in the field, never make their dear backs smart, nor let their dear stomachs get empty.

Human nature works out in slaveholders just as it does in other men, and in American slaveholders just as in English, French, Turkish, Algerine, Roman and Grecian. The Spartans boasted of their kindness to their slaves, while they whipped them to death by thousands at the altars of their gods. The Romans lauded their own mild treatment of their bondmen, while they branded their names on their flesh with hot irons, and when old, threw them into their fish ponds, or like Cato “the Just,” starved them to death. It is the boast of the Turks that they treat their slaves as though they were their children, yet their common name for them is “dogs,” and for the merest trifles, their feet are bastinadoed to a jelly, or their heads clipped off with the scimetar. The Portuguese pride themselves on their gentle bearing toward their slaves, yet the streets of Rio Janeiro are filled with naked men and women yoked in pairs to carts and wagons, and whipped by drivers like beasts of burden.

Slaveholders, the world over, have sung the praises of their tender mercies towards their slaves.

Many Alaskan slaves had been put into bondage after watching their families massacred, and lived their lives under the complete control of their masters. Though minimizing the violence and psychological torture of enslavement supports the claim that Sah Quah was a needless case, the notion that Alaska slaves were simply “part of the family” is a moral obscenity.

And what would have happened if Dawson had concluded that tribes had broad powers of sovereignty and that Alaska was, indeed, Indian Country? The argument that Sah Quah was brought in bad faith is typically premised on the assumption that the case was legally needless because the Thirteenth Amendment had already ended slavery in Alaska. This creates two problems: first, that those who decry the trial as a colonialist intrusion into Tlingit culture are stuck appealing to the legitimacy of the Thirteenth Amendment, which is itself an even earlier colonialist intrusion into Tlingit culture.

Second, it is not fully clear that the Thirteenth Amendment was sufficient at the time to ban slavery in Indian Country. The Thirteenth Amendment banned slavery in lands “subject to [U.S.] jurisdiction,” but Native American groups had broad jurisdictional powers in Indian Country–particularly when dealing in crimes between Native individuals–and slavery had not been one of the crimes included in the 1885 Major Crimes Act. In fact, treaties signed between the United States and several southern tribes that owned African-American slaves, signed in March and July 1866–months after the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment–include prohibitions of slavery in Indian Country. This has led Marquette University Professor J. Gordon Hylton to conclude that slavery in the continental United States did not end with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, but rather “came to an end as a legal institution on June 14, 1866, when the Creek Tribe agreed to abandon African-American slavery.” If Hylton’s legal reasoning is sound, then he is wrong only about the location and date at which slavery ended.

The motivations of those involved in In re Sah Quah remain opaque. M.D. Ball’s papers, which the Landmine obtained by request from Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, contain offhand references to slaves in Sitka prior to the trial but provide little insight into Ball’s attitude toward slavery itself. An obituary for Judge Dawson describes him as “probably the best known jurist in Northwest Missouri,” but, remarkably, does not mention In re Sah Quah.

It is possible that the men involved in In re Sah Quah harbored ulterior motivations for bringing the case. It is also plausible that agents of the United States, which had recently fought a catastrophic war to end centuries of Black enslavement in the contiguous United States, could have been motivated, at least in part, by a genuine desire to end enslavement occurring under their noses in Alaska.

X.

2022

In Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America, Leland Donald argues that even though slavery ended as an institution, the extreme stigma attached to it in indigenous communities persisted through many generations. Donald notes that some descendants of slaves retained a sense of shame and guilt over their ancestors’ status well into the twentieth century, and that slave ancestry could still be brought up during disputes.

The Landmine reached out to numerous members of the Alaska Native community to enquire about contemporary perspectives on the topic of Alaska slavery. Richard Peterson, the president of the Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, declined an interview request. Several members of the Alaska Native activism and educational community responded that they were aware that slavery had once been practiced in Southeast Alaska but knew little about it. Most employees at Alaska museums and historical institutions dedicated to indigenous topics were confused by the questions or surprised to hear that slavery had once been practiced in Alaska.

But nearly everyone the Landmine reached out to had the same suggestion: talk to Rosita Worl.

Dr. Rosita Worl (Tlingit: Yeidiklats’okw and Kaa.hani) is widely considered one of the foremost scholars on Alaska Native topics. Born in a beachfront cabin near rural Petersburg in 1938, Worl dodged an arranged marriage at age 13 to pursue her education, eventually receiving a master’s degree and Ph.D in anthropology from Harvard University. Worl has published a broad range of scientific studies, has taught at University of Alaska, sat on the board of the Sealaska Native Corporation for thirty years, served on the board of the Alaska Federation of Natives, and is currently the president of the nonprofit Sealaska Heritage Institute.

A page on the Sealaska Heritage website, titled “Q&A with Rosita Worl: Slavery Among the Tlingit,” is perhaps the only visible reference to Alaska slavery coming from within the Alaska Native community. Why, we wondered, had Worl decided to write—with apparent single-handedness, and in public—about Alaska’s history of indigenous slavery?

In a December 2, 2020 call, Worl told the Landmine that she shares the belief that In re Sah Quah was brought in bad faith, but also believes that the historical existence of slavery in Southeast Alaska should be acknowledged:

“I want people to know about our culture. I know that we achieved great sophistication, great complexity, and I have to acknowledge that it was the slaves who helped us develop that society. We tend to ignore it because we are Tlingit people—I know some of our people don’t like it all—but I say you can’t ignore it.”

Worl described looking out over the mudflats in Southeast Alaska and seeing the remnants of thousands of stakes that had been pounded into the mud long ago. That work, she said, would have been performed by slaves.

“To try to explain our society and the wealth we were able to accumulate you have to acknowledge that there was a slave pool that was doing a lot of that labor. As an anthropologist, as a sociologist and as a proud Tlingit I want to acknowledge our society, and to do that you have to acknowledge slavery.”

Denying or minimizing the practice of slavery, in Worl’s view, would not only be historically inaccurate but could endanger the credibility of those who promote Southeast Alaska indigenous cultures today. “Don’t try to romanticize our culture,” Worl said, “because anyone trying to study it will figure out it’s a lie.”

Worl described a complex and often contradictory range of reactions to slavery in the Alaska Native community over the preceding century: anger that slaves—valuable property—had been taken away by United States authorities without compensation, shame that slavery had been practiced at all, and lingering stigma toward the descendants of slaves. Worl cited a meeting in Ketchikan in or around 1990, in which a group of a hundred or more elders rejected the repatriation of indigenous human remains on the grounds that the remains were likely those of slaves. “That’s a story,” Worl said. “1990!”

Though many sources cite stigma toward the descendants of Northwest Coast slaves, this reaction is not universal. In a June 23, 2021 conversation, Alaska State Museum Curator Steve Hendrickson told the Landmine that his wife, who is Alaska Native, is proud of her descent from a Tlingit slave. Her ancestor, he said, was able to work hard after he was freed and rose to a place of prominence within the community. “So they actually like it that people know,” Hendrickson explained, “even though some other native people don’t want to talk about their heritage [of enslavement].”

There was one aspect of the legacy of slavery on which Worl and all other sources agreed: that only members of older generations still considered slave ancestry a source of shame. Younger generations rarely know who is descended from slaves, and if they do they attach little stigma to it. No matter their family history, younger people are moving into the future with a more united cultural identity and purpose.

Though systems of slavery may have persisted in Alaska longer than anywhere else in North America, its legacy of divisiveness within the community is now largely a thing of the past. Alaska, then, provides an example of something that seems both extraordinary and perhaps instructive: it is a place where the deep wounds of slavery have, over the generations, substantially healed.

XI.

Sah Quah

Though scholars and historians tend to focus on the legal questions raised by In re Sah Quah, after months of research another question increasingly surfaced: what had happened to Sah Quah? The Landmine scoured news archives, census records, and obituaries for traces of Sah Quah’s life following the trial. Had he gone back to his homeland? Settled as a freed man back into the Sitka community? Did he marry and start a family? Research revealed nothing.

Sah Quah’s appearance in written history is brief, and yet it provides cause for admiration. Sah Quah had endured a lifetime of tragedy incomprehensible to any Alaskan living today. He had been taken by violence from his family, his labor stolen, and his body sold as property. Many of those who write about In re Sah Quah today focus on the allegedly ulterior motivations of the attorneys and judge involved in the case, effectively decentering Sah Quah from the trial that bears his name. But even if the trial had been technically unnecessary from a legal perspective, even if participants had had ulterior motives, it is hard to see Sah Quah’s decision to trust the nascent Alaska courts and challenge the system that had enslaved him as anything but a remarkable act of courage. Who could possibly begrudge an enslaved person the opportunity, under any circumstances, to defy the system that had enslaved him?

Alaska is a place where slaves lived, worked, and died under the American flag. What we do with this knowledge is a topic for discussion. That discussion may be painful, and would call for sensitivity and grace. But to erase Sah Quah and the other enslaved Alaskans like him from our collective understanding of history because knowledge of them causes discomfort constitutes a second victimization–and one that is particularly cruel because we have the power to correct it.

In the town of Wrangell, the Chief Shakes Longhouse sits on a prominent point in the center of the harbor. This ornate reconstructed Tlingit structure is named for the line of Shakes chiefs, at least one of whom was reported to be a prolific killer of slaves. By contrast, there is nothing in Alaska named after Sah Quah.

Why, the Landmine asked Worl, isn’t there a single public building, park, or road named after Sah Quah? Why isn’t this courageous Haida man, who challenged a centuries-old system of enslavement in court–and won–an Alaska civil rights hero?

“Maybe some time in the future,” she responded, “he will be.”

Selected sources

- The Incorporation of Alaska Natives Under American Law: The United States and Tlingit Sovereignty, 1867-1900, Sidney Harring, CUNY School of Law, 1989

- Decision in Ex parte Crow Dog, Justia.com

- When did slavery really end in the United States?, J. Gordon Hylton, Marquette University Faculty Law School Blog, January 15, 2013

- Population and Resources of Alaska; Eleventh Census, 1890

- Social Structure and Social Life of the Tlingit in Alaska, R.L. Olson, 1967

- Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America, Leland Donald, 1997

This is an extraordinary piece of historical journalism. Bravo Landmine.

Great read.

You should look at the Aleuts on St Paul who we’re inslaved by NOAA for the seal harvest.

They were release in the late 70’s.

It will forever amaze me how Landmine has all these sloppy takes on Twitter and runs the ”loosest” stories and then turns around and produces these INCREDIBLE pieces of standout journalism. This, along with your Campbell Lake piece, article about Ethan’s resignation, and your videos about homelessness have been truly exceptional and are much needed in our media landscape. Less Tweeting, and more of this, Landfield!

I know this piece is already very long, but I was curious about why Alaska’s educational institutions and museums have ignored this aspect of Alaska history. Of course I can understand why some folks would be uncomfortable with the topic but the fact that nobody has covered this before really needs some explanation. I would have liked to hear from a museum director or someone at the Alaska Native Heritage Center about why Alaska slavery is not being acknowledged. It is clear from this article that the evidence for slavery in Alaska under American rule is very extensive. Thank you.

This history is acknowledged, as the article demonstrates, given that Dr. Worl published her blog post in 2017, and given that you can find any number of books that at least mention the existence of slavery on the Northwest Coast, if they don’t necessarily discuss it in depth. I’m not sure how you could prove the negative that it is “not being acknowledged.” I’ve been learning about the Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast since I was a child in the ’90s, and I can’t remember when I first learned about slavery existing among Native peoples here, since it was… Read more »

The history of Alaskan Natives is long and tortured. There was mass starvings, there was inter and intra tribal warfare, and as mentioned here slavery. Being an Alaskan Native precontact with the western world was not an easy life by any means. It does a disservice to these people to pretend the past did not happen. All humanity has enslaved other humans, all humanity has killed other humans, that is a part of humanities past, present, and future.

You failed to note the sexual abuse of slaves (men, women, children) that was allowed, as well as the fact slaves were often eaten. Nor is the culture of slavery completely gone. In SEARHC, the main native hospital in Sitka you will find a craved house panel just inside the main entrance placed there to represent the buildings status as a native lodge. Above this panel, in each corner you will see a bloody handprint that represents a slave that was placed in the hole when a new lodge was being built. The house pole was dropped into the hole… Read more »

Extensive, codified, brutal slavery. Reading this article, I had an inkling about disgrace among slaves who returned to their people, and then read that this was so. There’s so much I don’t know about history. This is extraordinarily well written in depth research. They should win a Pulitzer. I glossed over one seeming typo. It appears there’s another at the end of section 6, “laws and costumes” is probably supposed to read “laws and customs,” unless this is an old spelling usage. Bringing this through the Sa Quah court case to examine legal proceedings as a way to subjugate Alaskan… Read more »

Thank you for this illuminating piece. Allow me to add that slavery among the Haida people is discussed in “Memories of Kasaan,” a cultural heritage project conducted in 1971 by the Alaska State Museum and the U.S. Forest Service. I found a link to that paper on the website of Kavilco, Inc., a corporation representing the Organized Village of Kasaan on Prince of Wales Island. The paper seems to be the transcription of an oral-history project conducted with three Haida informants, including Walter B. Young, Sr. Born in 1887, Walter Young was the descendant of a slaveholding family. In some… Read more »