In a recent opinion piece in the Peninsula Clarion, Representative Bill Elam (R – Nikiski) raises an issue that deserves substantial attention in the continued debate about further K-12 funding.

In large part, Elam’s op-ed is about local governments’ role in school issues. Here is the gist:

The State of Alaska provides nearly 60% of all K-12 education funding. That support must be stable and predictable, so our students and teachers aren’t left in limbo. But here’s what many folks don’t realize: the remaining 40% comes directly from local taxpayers — through property taxes, sales taxes, and borough appropriations. … That’s not just significant — it’s intentional. Our community is intended to be invested in our schools. And that means we should have a strong say in how they’re run.

… I support local control — and with it, local accountability. It’s not enough to point fingers at the state. If you want to know who’s shaping your schools, start with your school board, your borough assembly, and your mayor. These officials manage facilities, select superintendents, adopt curriculum, and make the decisions that affect your child’s education.

If there’s waste or mismanagement, that conversation starts with your local leaders — not just your legislator. And if cuts are needed, they should begin locally — where the public has direct oversight — not top-down mandates from Juneau.

We agree strongly with the point. Issues related to costs and efficiencies are decided mainly at the local level, by local school boards, assemblies, and mayors. To create a strong incentive to pursue those, the localities must have substantial “skin in the game” – what Elam refers to as “accountability” – in terms of funding. If they don’t – if all or most of the funding comes from elsewhere – there is no incentive to control costs and seek efficiencies. Spending more doesn’t cost anything to those making the decisions; it’s all just free money.

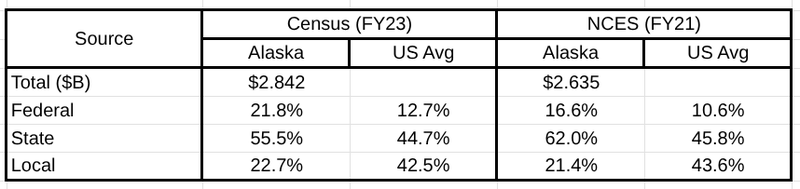

Looking at the national statistics, it’s clear that Alaska creates far less “skin in the game” at the local level than other states. There are two primary sources of information nationally about the sources of K-12 funding: one set is published by the U.S. Census Bureau, and a second by the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Most other sources appear derivative of those two.

Using the most recent, publicly available set of statistics from each, here is how Alaska stacks up in terms of percent of funding derived separately from federal, state, and local sources compared to the national average.

Using the most recent Census Bureau data, which covers Fiscal Year (FY) 2023, the Federal government provides 12.7% of the funding for K-12 on average across the nation, the states provide 44.7% and local sources provide 42.5%. Looked at another way, setting aside the federal share, the states provide 51% of the combined state and local funding, and local sources provide 49%.

The results are similar using the latest NCES data, which covers FY 2021. There, on average across the nation, the federal government provides 10.6% of total K-12 funding, the states provide 45.8% and local sources provide 43.6%. As with the Census Bureau data, focusing solely on the state/local split, the states provide 51% of the combined state and local funding, and local sources provide 49%.

Alaska is significantly out of step with those averages. Using the Census Bureau data, in Alaska, the federal government provides 21.8% of total K-12 funding, the state provides 55.5% and local sources provide 22.7%. Focusing on the state/local split, the state provides 71% of the combined state and local funding, with local sources supplying only 29%.

From a local funding perspective, Alaska’s results using the most recent NCES data are even worse. There, the federal government provides 16.6% of total K-12 funding, the state provides 62% and local sources provide only 21.4%. From the perspective of the state/local split, the state provides 74% of the combined state and local funding, with local sources providing only 26%.

Viewed in terms of the percent of local contribution, Alaska ranks sixth lowest in the nation using the Census Bureau data and 4th lowest using the NCES data.

As some will quickly point out, the numbers for Alaska are averages, with the level of local contribution varying widely across the state’s K-12 districts.

Using the most recent (FY24) funding data from the Alaska Department of Education and Early Development (DEED), inclusive of State of Alaska PERS/TRS Payments, the statewide Alaska averages from the perspective of the state/local split are the same 71% (state) and 29% (local) as reflected in the national data. The district data vary from a local funding low of 0% (local) and 100% (state) to a high of 67% (local) and 33% (state).

Of the 53 K-12 districts in the state, however, only five, containing less than 3% of the statewide total average daily student count taken during October (ADM), have a local contribution level higher than the national average of 49%. The remaining 48 districts, representing more than 97% of the statewide ADM, fall below the national average.

Of those, several districts, accounting for 20% of the statewide ADM, have a local contribution level of less than 10%. Districts that, combined, represent over a third of the ADM, make local contributions that represent more than 10%, but still less than 33% of combined state and local funding. Districts that, combined, represent nearly 80% of the ADM, make local contributions of more than 10%, but still less than the national average of 49%.

Of the state’s largest districts, Anchorage’s local contribution of 38% of combined state and local funding, Fairbanks’ 32% and Mat-Su’s 27%, all fall well below the national average, and in the case of Mat-Su, fall even below the state average.

Looking at this data, it is little wonder that, in the face of stagnant revenue and declining student population, Alaska is failing to identify the level of cost savings and efficiencies in K-12 spending, such as the level of district consolidation prevalent in other states, that might be anticipated in such circumstances. With the majority, and in most districts, the vast majority of funding supplied by the state, there is limited incentive for local district management to seek out savings. Indeed, doing so would have the perverse effect of reducing the injection of “outside” (i.e., state) funds into the local economy.

Instead, because it has a limited impact on the constituencies from which they are elected, the incentive is for local district management to paper over any issues by continually pushing for increased state K-12 funding. From the perspective of the local economy, such an approach requires, at most, a limited diversion of additional resources from local sources. Instead, such an approach carries the upside of growing the local economy by injecting into it even more “outside” (i.e., state-level) money.

In short, by creating pressure for increased state funding, the failure to push for cost control and efficiencies at the local level is a money maker for the local economy, not, as elsewhere in the US, a significant local money loser.

According to a recent edition of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, in a recent session focused on developing its annual list of legislative priorities, the Fairbanks North Star Borough (FNSB) Assembly discussed proposals urging the Legislature to change the way the state’s basic need formula is written.

Rather than move Alaska closer to the national average, however, the proposals would reduce even the relatively minor contribution most local governments already are making.

One request involves the state fully funding education to meet basic needs and eliminating the requirement for local contributions. [Borough Mayor Grier] Hopkins [D-Fairbanks] proposed an amendment, moved by Assemblymember Nick LaJiness, to include a legislative request that the state not reduce education funding as communities grow. Hopkins argued that reduced funding places the burden on local taxpayers’ shoulders. …

Hopkins’ proposed legislative priority also requests that the state not reduce funding should the borough enact a voluntary property tax exemption to spur economic development. If the Assembly were to approve an exemption to spur housing development, the state could distribute less education funding based on the artificially lowered property values.

We certainly agree with Mayor Hopkins that “the Legislature [should] change the way the state’s basic need formula is written.” The change should be in the opposite direction from what was considered at the FNSB Assembly meeting, however. Rather than further reducing the already low level of local contribution, the change should be to increase the required local contribution until it more closely approximates the national average and reaches the tipping point of creating positive incentives for focusing locally on cost constraints and efficiencies.

In future columns, we intend to return to this subject to discuss potential changes to the current statutes governing local contributions, which would better incentivize local bodies to focus on cost savings and efficiencies within the various districts. At the core will be proposals to increase the level of required local contributions more toward the national average, and with it, create some sort of cost-sharing of increases so that the localities also feel a significant impact from increased spending.

For starters, however, any further near-term increases in K-12 funding should be accomplished, in substantial part if not entirely, through increases in the required level of local contribution rather than through additional state budget appropriations. Looking at the national data, there certainly is room for significant increases in local K-12 support in Alaska. And it better aligns the incentives for achieving cost constraints and efficiencies with those who have the power to implement them.

We believe that imposing such a requirement will also help limit pushes from local bodies for increased state assistance only to those instances where the local bodies are willing to put their own local communities’ money where their mouth is.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

The article doesn’t mention Impact Aid that Feds pay because military bases are not subject to property taxes, but military bases have significant impact on school districts. I would suspect between Eilelson and JBER that’s a lot of value that local municipalities cannot tax.

The localities can raise their share of revenues in other ways (e. g., a sales tax) that would avoid that problem. If they nonetheless choose to continue to rely solely or primarily on property taxes, they are creating the problem themselves, hardly a reason to excuse them from meeting a broader obligation.

LOL……..

“………The localities can raise their share of revenues in other ways (e. g., a sales tax)…….”

Well, at least you make the same noises even when the subject isn’t the Permanent Fund……..

It would be interesting if the tune changed if a school voucher system would be allowable.