In last week’s column, we examined the impact of what was anticipated in Governor Mike Dunleavy’s (R – Alaska) proposed fiscal plan, based on news reports at the time.

Since then, the Governor has introduced legislation that incorporates his actual plan, which differs somewhat from the projections on which we based last week’s column. As a result, in this week’s column, we update some of the work from last week, as well as take a deeper dive into his proposed reductions to both the general and petroleum corporate income taxes. In addition, we compare the impact of the sales tax he has proposed with continuing to raise the same amount of revenue through incremental reductions in Permanent Fund Dividends (PFDs).

While an equally important issue, to avoid overload, we will defer assessing his proposed changes to oil taxes until next week. (But spoiler alert, we think the proposed changes fall woefully short of what is required to meet the mandate of the Alaska Constitution to provide for the development of the state’s natural resources for the “maximum benefit” of its people.)

The Governor’s proposed fiscal plan raises revenue through several provisions. Some of those are reflected in Senate Bill (SB) 227, with the amounts raised noted in the fiscal note for that bill. But those aren’t all of the measures that qualify as the “New Revenue Measures” contemplated in the administration’s initial Fiscal Year (FY) 2027 10-Year Plan.

Senate Joint Resolution 23 also contributes toward the goal by effectively lowering the PFD from current statutory levels to 50% of the annual percent-of-market-value (POMV) draw from the Permanent Fund (POMV 50/50). The current statutory levels were incorporated into the spending levels reflected in the initial FY2027 10-Year Plan. Substituting POMV 50/50 for those increases the revenue from the POMV draw available to the general fund. Another step is reflected in SB 223, which proposes to cap spending increases below those projected in the initial FY2027 10-Year Plan.

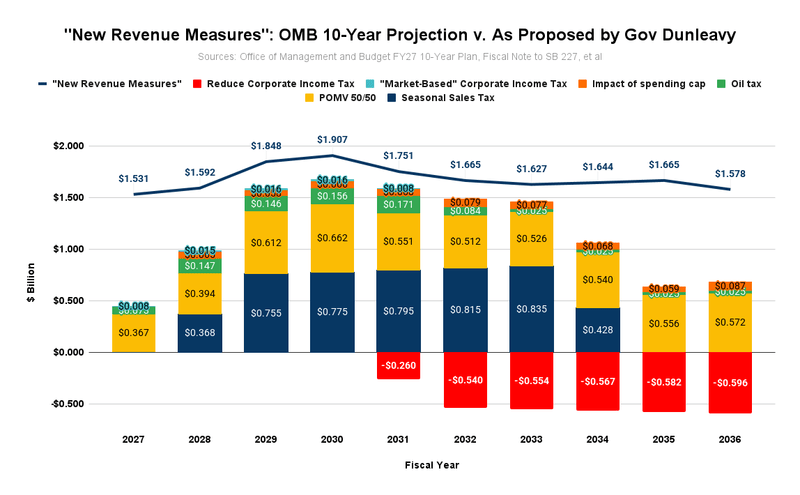

In the following chart, we break down the impact of the measures filed by the Governor by year (the bars), compared with the overall target for the “New Revenue Measures” in the administration’s initial FY 2027 10-Year Plan (the solid blue line). (We note that earlier this week, the administration’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) posted a “Revised” FY2027 10-Year Plan. As of this week’s column, we are still working through those revisions to identify any significant differences from the projections in the initial FY2027 10-Year Plan. At first blush, there appear to be a few, which we will discuss further in next week’s column.)

As is clear, while the administration’s proposed seasonal sales tax is the most significant contributor to “new” revenues for the duration it remains in effect, reducing the PFD from the current statutory level to a POMV 50/50 split is not far behind and becomes the largest once the sales tax expires. One significant difference from the chart we developed last week is the impact of the general and petroleum corporate income tax reductions (shown in red). In last week’s chart, those reductions had no significant effect until FY2036, the end of the period. As proposed by the Governor in SB 227, however, the impact begins much earlier, in FY2031, and grows significantly deeper over time.

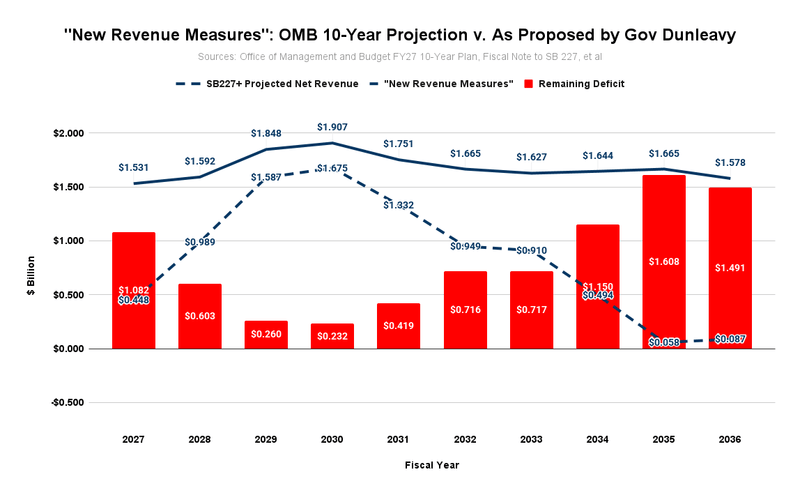

In the following chart, we compare the amount of “New Revenue Measures” targeted in the initial FY 2027 10-Year Plan with the net amount of “new” revenue raised under the proposed measures.

As in the previous chart, the solid blue line represents the targeted amount for the “New Revenue Measures” reflected in the initial FY2017 10-Year Plan. The dashed blue line reflects the net of the “new” revenues actually raised by the Governor’s proposals. The remaining deficits relative to the levels projected in the initial 10-Year Plan are shown in the red columns.

As the chart demonstrates, the “new” revenues actually raised by the Governor’s proposals remain below the levels targeted in the initial FY2017 10-Year Plan throughout the entire period. While, as the impact of the proposed reduction of the PFD to POMV 50/50 and proposed sales tax build, the deficit levels shrink in FY2029 and 2030, they begin to grow again in FY2031 and subsequent years as the effect of the elimination of the general and petroleum corporate income taxes and expiration of the sales tax takes its toll.

Indeed, by the end of FY2035 and FY2036, the negative impact of eliminating the general and petroleum corporate income taxes is so large as to drive deficit levels back to nearly those the administration initially projected in the initial FY2027 10-Year Plan.

The Governor argues that the deficits in the latter years will be fully offset by increased revenues from new oil development and the Alaska LNG Project (Alaska LNG or Project). But not only is that claim highly speculative, there is also no basis for it.

As we noted in last week’s column, the initial FY2027 10-Year Plan already includes anticipated production volumes and related revenues from the Willow and Pikka oil projects, the state’s two major “new resource development projects,” which are projected to come online during the Plan’s time frame. To our knowledge, no other “resource development projects” are scheduled to go online during that period that would add material revenue.

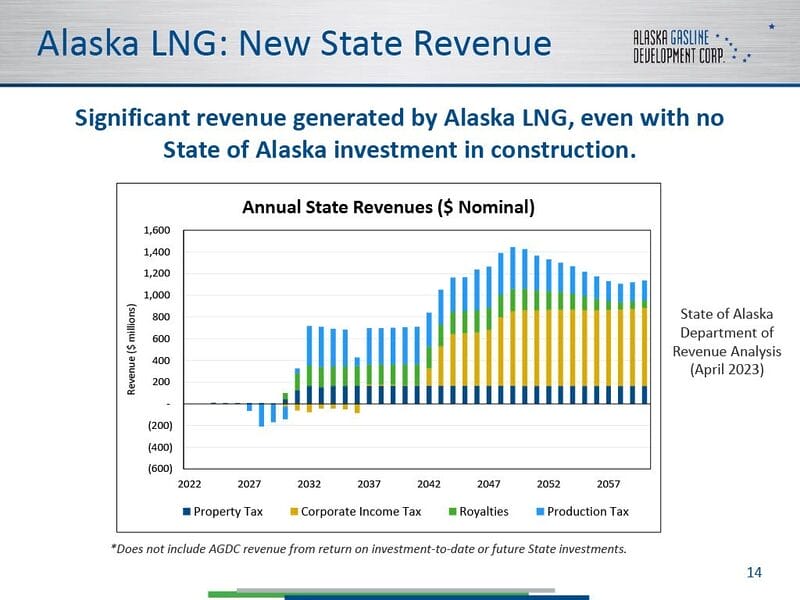

And not only is the likelihood of the “yet-to-be-finalized” Alaska LNG project highly speculative at this point, but so is the level of its potential contribution to state revenues even if it is. The most recent public estimate of potential state revenues from the proposed Alaska LNG project we can find is the following one-page slide included in a 2023 Alaska Gasline Development Corporation (AGDC) presentation.

When reviewing this chart, keep in mind that, in another bill the Governor has said he intends to submit this session, he will propose reducing the property tax applicable to the Project (the dark blue bars) by 90%, presumably reducing the roughly $175 million currently projected in annual state revenue from that source to less than $18 million. While outside the period currently at issue, note also that a significant source of revenue from the project after approximately FY2042 is “corporate income tax,” which the Governor now proposes also to eliminate.

Even without accounting for the potential reduction in property tax, the Project is projected within the period to reduce state revenue from FY2027 through FY2029, only contribute a minor amount in FY2030, roughly $300 million in FY2031, and $700 million per year in each of FY2032 through FY2035, before falling back to $400 million in FY2036 (all including property tax at full rates). Even in the unlikely event that the Project proceeds, at these levels the projected revenues are insufficient to close the remaining deficits projected in the administration’s initial 10-Year Plan in any years other than, possibly, FY2032 and 2033, the last two years also of the Governor’s proposed sales tax.

The projected revenues from the Alaska LNG Project – at least those currently available publicly – don’t even come close to offsetting the projected deficits in the years after that.

If the Dunleavy administration and Legislature are serious about closing the deficits projected throughout the initial 10-Year Plan, at a minimum, they should defer any decisions both to sunset the sales tax and eliminate the general and petroleum corporate income taxes until much more is known about potential revenue levels beyond the end of FY2030. Based on current projections, either step would plunge state finances back into the fiscal abyss. The state should not spend time resolving its budgetary picture in the early part of the period, only to allow it to return to shambles afterward.

Separately, we want to address the argument that the Governor’s proposed sales tax should be rejected as regressive. We don’t disagree that sales taxes are regressive, but the choices the state faces are relative.

The state’s budget must be balanced. Given recent history, it seems likely that if the projected budget deficits are not closed by “new revenue measures” along the lines suggested by the Governor, they will instead be closed by continued, ever-deepening reductions in the PFD.

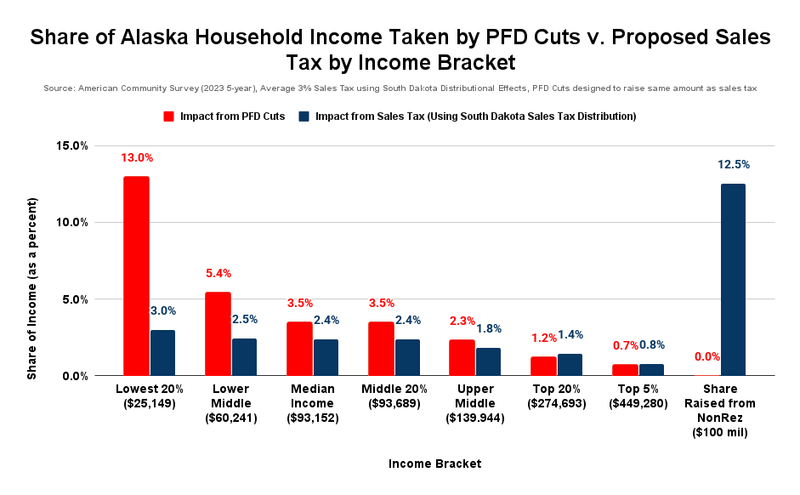

To analyze the trade-off between the two, we have developed the following chart, which compares the impact of closing the projected deficits through additional PFD cuts versus the Governor’s proposed sales tax by income bracket.

The percentage impact on income of closing the projected deficits through additional PFD cuts is shown in the red bars, while the effect of closing the projected deficits through the proposed sales tax is shown in the blue bars. The numbers are not additive. As proposed by the Governor, the sales tax would substitute for PFD cuts of the same size.

On the right side of the chart, we also show an estimate of the share of revenue proposed to be raised by the different approaches from non-residents. None of the revenue raised by PFD cuts would come from non-residents. Because PFDs are paid only to Alaskans, any reduction would be borne entirely by Alaska families.

On the other hand, based on updated data from a new study released earlier this week by the University of Alaska-Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Policy (ISER) on the “Economic Impacts of Alaska Fiscal Options,” between 24% and 26% of revenue from the proposed sales tax would come from non-residents. For convenience, we use 25% as a placeholder.

The fact that a sales tax would raise significant revenue from non-residents is critical to comparing the impact of the two approaches on Alaska families. By reducing the revenue required from Alaska families, a sales tax significantly reduces the impact on those families compared with raising all of the necessary revenue from them through PFD cuts.

The differences are telling. While using PFD cuts to raise the same amount of revenue estimated by the Governor to be raised through the proposed sales tax would reduce the income of Alaska families falling in the lowest income bracket by approximately 13%, the sales tax would reduce their income by only approximately 3% on an annual average basis, even if all of their income was used to purchase goods and services subject to the tax.

Using the same distributional effects as estimated by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) in its most recent “Who Pays” analysis for South Dakota’s sales tax, on which the Governor’s proposal is patterned, the relative impact of the sales tax on lower middle, middle and upper middle income Alaska families would be the same: their income would be reduced less using the Governor’s proposed sales tax than using PFD cuts.

Put another way, 80% of Alaska families would keep more money in their pockets by restoring the PFD to a 50/50 POMV and paying the proposed sales tax, rather than continuing to cover the deficits entirely through PFD cuts.

And while the share of income taken by the sales tax from those in the upper income brackets would be slightly higher than the impact of using PFD cuts, the share taken would still be less than the level taken from the remaining 80% of Alaska families. It should be hard for those in those brackets to complain about the change if they are still being treated preferentially.

Some argue that a progressive, or even a flat, income tax would be preferable to a sales tax because it would further reduce the impact on middle- and lower-income Alaska families. That’s possible, although ISER’s new study suggests that at least some versions of an income tax might raise less as a percent from non-residents than the Governor’s proposed seasonal sales tax, leaving Alaska families with a greater overall share of the burden, which would need to be accounted for through higher average rates.

But some suggest that an income tax has an even smaller chance of passing the Legislature and being signed by the Governor than his proposed sales tax. Given the lower impact on 80% of Alaska families than continued PFD cuts of even his proposed sales tax, those genuinely concerned about the economic situation faced by middle and lower-income Alaska families should ensure that they at least take that win, rather than let the “perfect” of an income tax become the enemy of, from the perspective of middle and lower-income Alaska families, still a “good” sales tax.

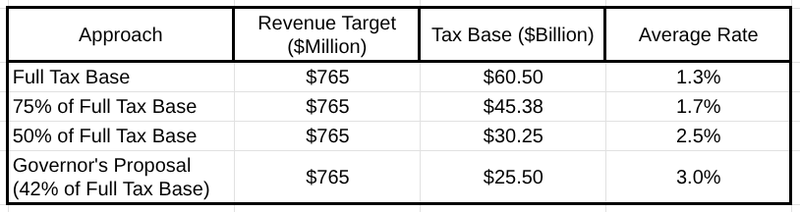

As we explained in last week’s column, we believe that, given the alternatives, an average annual overall tax rate of 3% is too high. Instead of trashing the overall approach, however, we believe the issue can be best addressed by expanding the base to which the tax applies. Even adapting the broad-based South Dakota approach still excludes a significant share of Alaska’s overall goods and services.

Using the latest figures from the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Alaska’s Private Sector Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – the total of the private sector goods and services produced annually in Alaska – is roughly $60.5 billion. The Governor’s proposed tax base covers less than half of the potential tax base.

As the following chart shows, the same revenue target can still be achieved at lower rates by simultaneously broadening the base.

One potential example of broadening the base is to apply it generally to all crude oil produced in the state. Under the South Dakota approach, while crude oil sold for use within the state is subject to the tax, crude oil exported from the state is not.

According to the latest BEA figures, roughly $9.6 billion (or 15%) of Alaska’s current GDP is from “Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction.” However, only a small portion of that is consumed in the state and is therefore currently subject to the proposed tax. Assuming including the portion exported would add approximately $8.5 billion to the base, the rate could be lowered to 2.25% and still raise the same amount of revenue.

In next week’s column, we intend to address any significant differences between the administration’s initial and “revised” 10-Year Plans, as well as take a deeper dive into its proposed changes to oil taxes, including the proposed elimination of the petroleum corporate income tax. As space allows, we also intend to start exploring the new ISER study, one of the single most important pieces of Alaska fiscal analysis we have seen over the last several years.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Stop Alaska Big Oil from looting the taxpayer.

Dunleavy didn’t propose a fiscal plan; he proposed a big “fuck you” to the State of Alaska as he heads out the door.