The latest report on the Alaska LNG project submitted by legislative consultants Gaffney, Cline & Associates – “Key Issues – Legislative and Policy Options for Alaska LNG – FINAL COPY” – published by the Legislature’s Legislative Budget and Audit Committee in December (the “Gaffney Cline Report” or “Report”) raises several issues that we anticipate digging into deeply as the coming legislative session progresses.

The one that we want to start with does not relate directly to the project itself, however. Instead, the issue concerns the potential for the legislative package some anticipate being offered soon in support of the project to affect the state’s oil tax code. The Gaffney Cline Report raises that potential directly in Section 1.4, which discusses the “interplay” between oil and the project. There, the Report says:

In the context of the LNG project, new legislation that creates a tax or royalty mechanism that links oil and gas revenues, potentially changing over time, could be created to better align the commercial interests of the oil producers with the fiscal requirements of the state.

It is not clear from that passage or elsewhere in the Report what type of “linkage” or modifications to the current tax and royalty structures Gaffney Cline has in mind for the new legislation. But as we have explained in previous columns, we agree that significant legislative steps are required in the very near future “to better align the commercial interests of the oil producers with the fiscal requirements of the state,” at least in terms of the state’s current production tax structure.

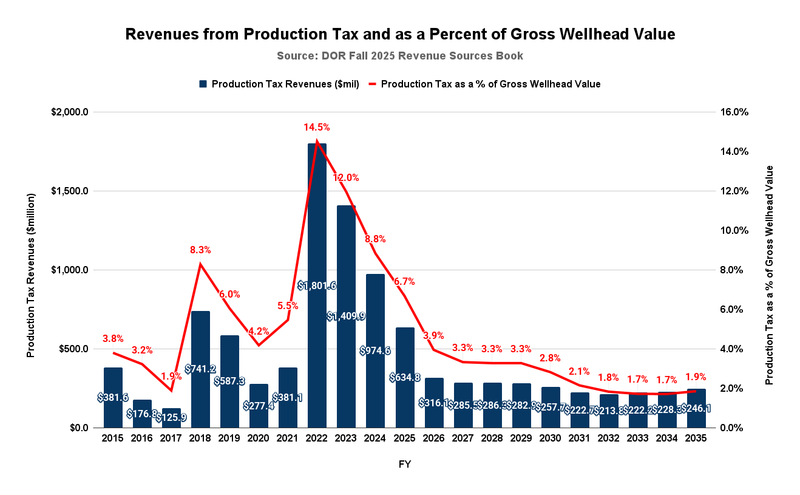

The following charts the amount of production taxes received by the state over the past ten years, for Fiscal Year (FY) 2025, and projected to be received over the next ten years as reflected in the recent Fall 2025 Revenue Sources Book (Fall 2025 RSB) published by the Department of Revenue (DOR), together with the percent of gross wellhead revenues they represent.

We have calculated the amount of gross wellhead revenues for each year by multiplying the “ANS Wellhead Weighted Average [Price] All Destinations” reported and projected by DOR for each year by the corresponding total production volumes, net of the volumes attributable to the state and federal royalty shares (which are not subject to tax). Because DOR does not include them in the report, we have estimated the royalty shares at 12.5% of the reported produced volumes, the general standard used in both Alaska and federal leases.

While the amounts and percentages vary year to year, one thing is crystal clear. Despite all three periods being governed by the same oil tax regime (what is commonly referred to as “SB21”), the levels of revenue and production tax, as a percentage of gross wellhead value realized by the state, are dramatically different between the first two periods and the third. The level of revenues and the percentage of gross wellhead value realized by the state as production taxes over the last ten years and in FY2025 are significantly higher than those anticipated over the next ten.

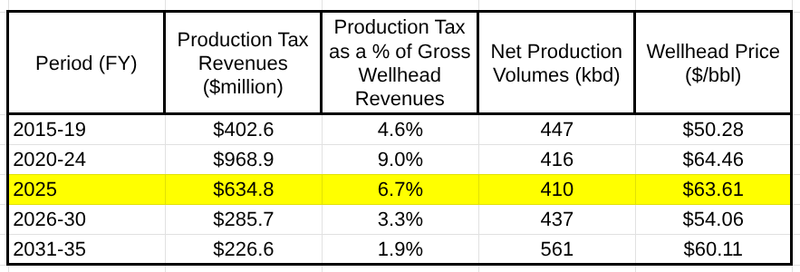

To demonstrate the differences, using the information in the Fall 2025 RSB, we calculate the average annual results for 5-year increments on each side of FY25 in this chart.

Over the ten years before FY2025, production tax revenues averaged $685.7 million per year, or 6.8% of Gross Wellhead Value. During FY2025, production tax revenues were within $50 million of the previous period’s level, at 6.7% of Gross Wellhead Value.

Over the ten years after FY2025, however, production tax revenues are projected to average only $256.2 million per year, or 2.6% of Gross Wellhead Value. More importantly, unlike in the earlier ten-year period, they are projected to decline dramatically over the next ten years, with revenues averaging only $226.6 million, or 1.9% of Gross Wellhead Value, over the last five years.

Some occasionally claim that lower production volumes and wellhead prices drive the differences between the periods. But as the chart demonstrates, that claim is demonstrably false.

While production tax revenues are at their lowest during the FY2031-35 period, production volumes are at their highest. While wellhead prices are not at their highest over the entire period, they are significantly higher than during FY2015-19, when production tax revenues were still nearly 80% higher and the level of production tax as a percent of gross wellhead volumes was almost 2.5 times higher.

Projected wellhead prices and production volumes are also significantly higher from FY2031-35 than from FY2026-30, when production taxes are still more than 25% higher, and the level of production tax as a percent of gross wellhead value is nearly 75% higher.

In the past, some have also claimed that the differences are due to the increase in production levels from federal lands over the latter periods. But that has zero effect. State production taxes apply equally to production from both state and federal lands at issue during the period.

When provided with information about the substantial decline over the whole period in the level of production tax as a percent of gross wellhead value, some express significant surprise, claiming that they thought SB21 provides for a “Minimum Tax Floor” of 4% of gross wellhead value, regardless of the level of costs being incurred by producers or any other factor.

While that was one of the “headlines” about SB21 touted at the time of its adoption in 2013 and generally has applied from its inception through FY2025, the reality is that there is a significant exception which, as SB21 ages, is projected to drive the rate well below the Minimum Tax Floor from FY2026 forward.

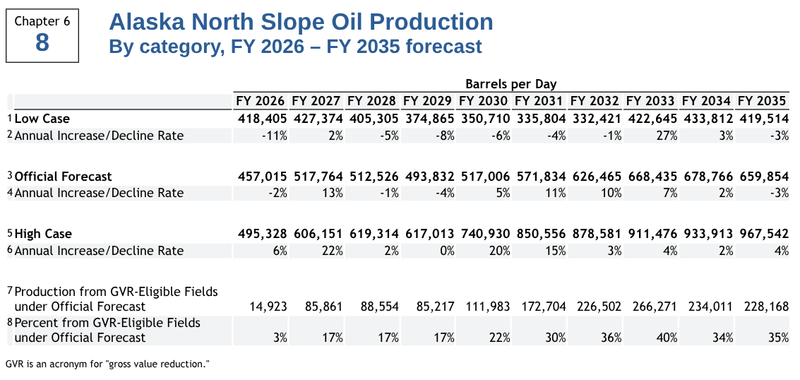

Under SB21, “Per-Taxable-Barrel Credits for Gross Value Reduction (GVR) Production” can be used to reduce tax below the Minimum Tax Floor. This is unlike the normal “Per-Taxable-Barrel Credits” discussed often in the past, which reduce production tax but may not be used to reduce it below the Minimum Tax Floor. As explained in the Fall 2025 RSB, GVR credits apply to production from “newly developed units, as well as certain new producing areas or expansion of producing areas.” As output from that type of unit grows, so does its impact on production taxes.

In addition to the credits, gross revenue from production from GVR-eligible fields is entitled to a 20% to 30% exclusion from the production tax calculation. That means if a field eligible for GVR treatment is otherwise producing $100 million per day in gross wellhead revenue, only $70-$80 million of that revenue is subject to production tax. The producer retains the remaining $20-$30 million in revenue free of production tax. Combined with the GVR per-barrel credits, the effect of the exclusion is to lower the state’s share of overall gross wellhead revenues even further below the minimum.

As projected in the Fall 2025 RSB, production from GVR-eligible fields (lines 7 and 8 in the following chart) is expected to grow substantially over the next ten years, rising from 3% of overall output in FY2026 to as much as 40% by FY2033 and 35% by FY2035. The effect, as noted above, is to drive the state’s share of gross wellhead revenues increasingly below the so-called “Minimum.”

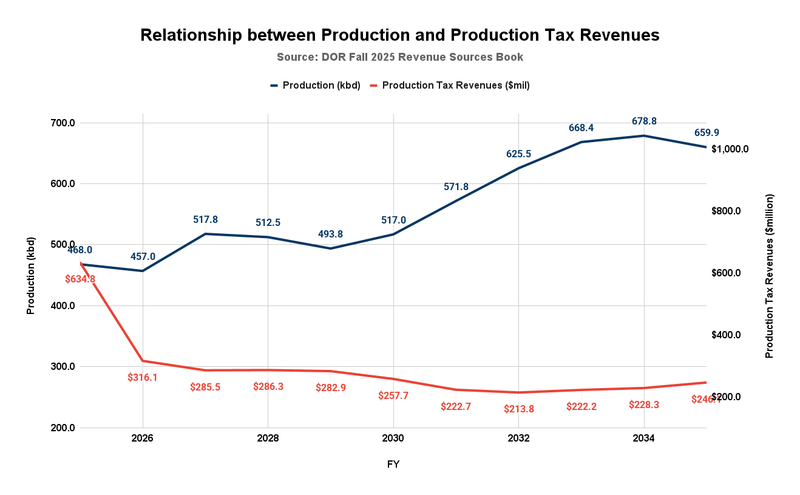

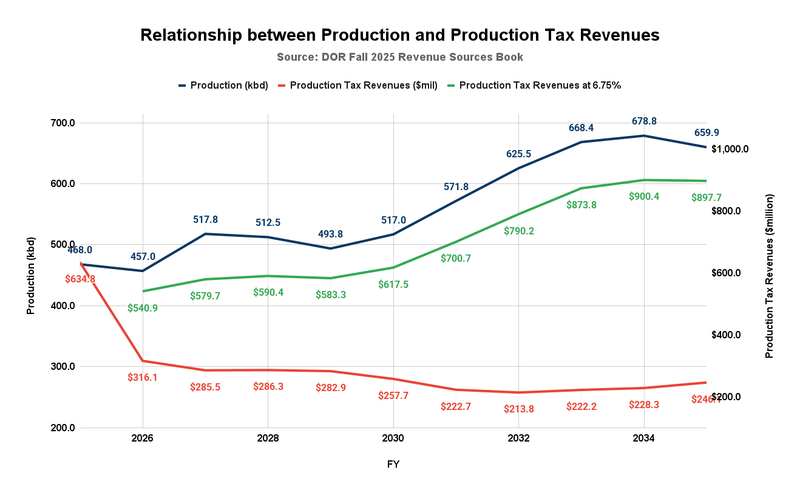

As we have explained in previous columns, these reductions are projected to occur even as production volumes and related producer revenues significantly increase. We chart the diversion here:

While production volumes are projected to increase over the period between FY2025 and FY2035 by 41%, from 468 thousand barrels per day (kbd) to 659.9 kbd, revenues from production tax revenues are projected to fall precipitously by 61%, from $634.8 million annually to $246.1 million.

In the words of the Gaffney Cline Report, that result certainly does not reflect an alignment of “the commercial interests of the oil producers with the fiscal requirements of the state.” The producers are realizing substantial revenue increases, while the state’s production tax, which, consistent with Article 8, Section 2 of the Alaska Constitution, is designed to capture a portion of that gain for the maximum benefit of the state’s people, is dropping like a rock.

Restating the production tax as a simple percentage of gross wellhead revenues would go a long way toward reversing the result and achieving the tax’s original objective.

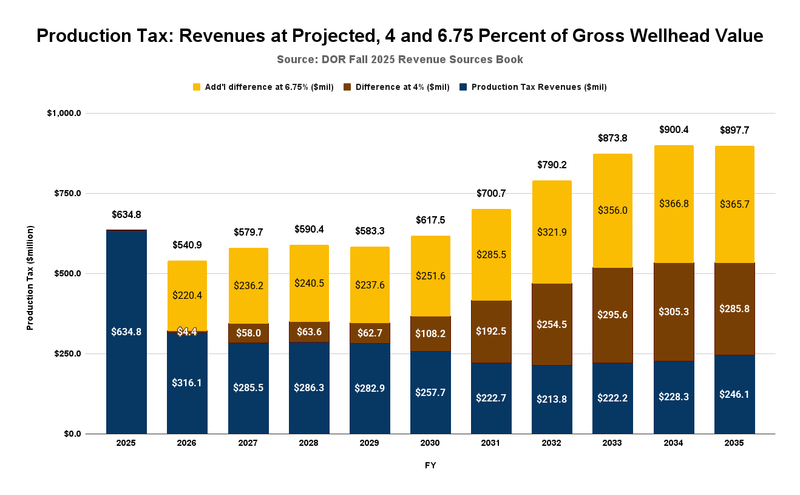

In the following chart, we have calculated the level of production taxes the state would realize if, instead of the highly complicated system the state currently uses, the state simply calculated production taxes at the 4% “Minimum Tax Floor” featured in the initial headlines around SB21. Over the ten years, production tax revenues would increase from an annual average of approximately $256 million to $419 million, an average yearly increase of $163 million.

We have also calculated the level of production taxes the state would realize if, again, devoid of the credits and exclusions, the state simply calculated production taxes at the roughly 6.75% rate realized over the first decade of SB21 and in FY25. Over the projected 10-year period, production tax revenues would increase by an additional annual average (over the 4% level) of approximately $288 million annually, for a combined average yearly increase of $451 million over currently projected levels.

As demonstrated in the following chart, the effect (in green) would be to create the result, as initially advertised during the passage of SB21, where production tax levels grow with production volume and producer revenues.

As we have explained in previous columns, SB21, as it enters its second decade, is badly broken. Despite the promises made at the time of its adoption in 2013 and its defense in the subsequent initiative election, it is not producing revenues consistent with the state’s obligation under Article 8, Section 2 of the Alaska Constitution. The state’s revenue share is not keeping pace as producer volumes and revenues grow; instead, it is declining rapidly. And the Minimum Tax Floor that some claimed would protect Alaskans against unanticipated problems with SB21 has proven wholly ineffective as the approach enters its second decade.

The Gaffney Cline Report is absolutely correct on this point. Significant changes need to be made in the state’s production tax structure “to better align the commercial interests of the oil producers with the fiscal requirements of the state.” Indeed, the need is so great that the required changes should be made in the very near future, regardless of whether there is a legislative package addressing the Alaska LNG project.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

This is a good article. I think you should do a follow-up where, for a number of provinces including Norway, Texas, and North Dakota, you total up what oil producers pay in royalties+production taxes+property taxes+etc, in other words, all the things that oil producers must pay to produce the oil, and then compare that to Alaska. My sense is that you will find that AK was sold a bad deal with all the oil company and support industry aliance money spent of SB21.

“………. I think you should do a follow-up where, for a number of provinces including Norway, Texas, and North Dakota, you total up what oil producers pay in royalties+production taxes+property taxes+etc, in other words, all the things that oil producers must pay to produce the oil, and then compare that to Alaska……….” I’d like to see that, too, but in detail. By that, I mean: * Cost to produce to the start of delivery. In Alaska, that would mean entry of the crude into the TAPS Cost of delivery to the refinery: to include pipe, rail, tanker ship, or any other… Read more »

“Reggie” … As a general proposition, you really need to start living in the 21st Century. What remained of the export ban was fully repealed in 2015. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-118

While there are spikes in some years (e.g., COVID), roughly 2% of ANS is now shipped annually to Asia.

Thanks for that. I knew of the temporary lift for shipment to Japan some years back, but was unaware of the full repeal. I hope the environmental industry is as unaware as I was. But that does not fully eliminate the demand problem. The world is quite literally awash with oil even as the worldwide Energy War continues unabated. I don’t know (and doubt you do) how long the current political games worldwide will continue, ease, or intensify, but I’ve got a strong feeling they aren’t going away anytime soon. Demand is down, manipulated heavily, and even as California prices… Read more »

“……..What remained of the export ban was fully repealed in 2015……….” Thanks for that. I was not aware of that good news. However: https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal95-1100446#_ “………Under the bill, Alaska would be allowed to export its oil unless the president found that it would not be in the national interest. In making such a determination, the president would have to take into account such factors as whether exports would diminish the quality or quantity of petroleum available to the nation, as well as to conduct an environmental review of the proposal………” I would imagine that the main reason the Biden auto-pen didn’t re-ban… Read more »

Also among Reggie’s problems . . . .

California’s existing refineries are far larger than they were in years past.

While 74% of California’s refineries have closed since 1980, state refining capacity has only decreased by 28%.

And that decrease is directly related to California’s success in increasing efficiency and in switching to renewable sources of energy.

Deapite a 65% increase in population since 1980.

Of course Reggie will learn nothing from this. As he will now demonstrate.

“………As he will now demonstrate……….”

Please explain for us all why West Coast states are paying the highest prices for gasoline and diesel in the nation.

“……..While 74% of California’s refineries have closed since 1980, state refining capacity has only decreased by 28%……..

…….Deapite a 65% increase in population since 1980……….”

^ Your words. Capacity decreased by 28%, population increase of 65%.

There’s more. California refines 100% of Nevada’s fuel and half of Arizona’s as well. Oregon has zero refineries. Zero. All of their fuel comes via a single pipeline from Puget Sound, and it went down a month or so ago. Caused a price spike.

Please tell us why West Coast states have the highest fuel prices in the nation, Dan.

Interesting how a comment I made twice has disappeared twice. Was it the mention of Marathon and Petro Star?

Thanks for re-appearing them.

“Reggie” is Kevin McCabe.

Are you Mike Alexander?

That explains why he’s so obsessed with Mike Alexander, the guy who busted him for multiple APOC violations over two campaign cycles.

Well, I’d love to ask Mike Alexander if he paid his APOC fine. That’s why I want to know if “Mike” is Mike Alexander.

That should be public record, anonymous coward. Or is this another time you want to play dumb about something that’s easy to access? You could also just pick up the phone and call the guy, but that might entail you blowing your anonymous coward cover. Probably check with your grifter buddy McCabe, too, to be sure he’s going to keep his APOC filings on the right side of the law this time. For a change. What do you think he was hiding those other two campaigns he got busted for when he didn’t want anyone to see what he spent… Read more »

“……..That should be public record, anonymous coward……….”

It is public record, I have read it, and I have some very special documents bookmarked here, ready to quote and link. I think “Mike” knows it, and he’s a bit smarter than you are openly doxing yourself and behaving like a Minneapolis “peaceful protester”. He needs to be more careful using your tactics, to include calling others “anonymous coward” while remaining anonymous himself.

You sound big mad, anonymous coward. Do you imagine you can have someone arrested for calling you an anonymous coward? Do you imagine you can sue someone for defaming you, despite it being a legal impossibly for an anonymous coward to claim defamation or injury to his tender feelings? Only you have the power to not be an anonymous coward. But that takes character and integrity that you clearly lack. But I appreciate that you don’t dispute that Rep. Kevin J. McCabe of Big Lake needs to keep his APOC filings legal for a change. Hard to believe he’d be… Read more »

“……..Only you have the power to not be an anonymous coward………..”

Actually, the vast majority of commenters on this website have the power to not be “anonymous cowards”, because few are as stupid as you are to dox themselves, especially when behaving in such an openly hostile and aggressive manner. Nobody wants to deal with a maniac following them around the grocery stores and community with his mouth blaring or shooting fireworks at the end of their driveway.

Keep it up, Editor. You’re doing it to yourself. The mean, ole’ Reggie isn’t doing it.

https://energynewsbeat.co/californias-oil-rush-slips-into-final-act-and-may-take-alaskas-oil-rebound-down-with-it/

“……..If California’s demand for Alaskan oil falters—due to refinery closures and net-zero transitions— the consequences could be profound. Alaska’s ANS exports face an “uncertain future,” potentially forcing shipments to Asia amid higher transport costs and geopolitical risks.

For Alaskan investors, this means stalled projects: exploration halts create a “cascade effect,” freezing multi-year investments and thousands of jobs.

Reduced demand could lower revenues, making high-cost Arctic developments uneconomical and deterring capital inflows.In California, consumers already pay a premium—$4.57 per gallon on average—with further spikes likely from distant imports replacing Alaskan crude………”

As California sees increasing refinery closures (which will reduce Alaskan crude demand), investors work to supply the region with fuel from east of the Rockies. “.The Western Gateway Pipeline is a joint Phillips 66 and Kinder Morgan project building a new pipeline from Borger, Texas, to Phoenix, Arizona, and reversing existing lines (SFPP, Gold Pipeline) to create a major refined petroleum product corridor from the Midcontinent to the West, serving Phoenix, Las Vegas, and Southern California. It aims to enhance energy security for Arizona, which lacks refineries, by delivering up to 200,000 barrels of fuel daily to meet growing demand, with operations ramping… Read more »