An exchange earlier this week with an interested reader helped us realize that some aren’t appreciating the full impact of various fiscal options on Alaska families and, through them, the overall Alaska economy. In this week’s column, we attempt to make those clearer.

Some start with the simple, and correct, assumption that, all other things being equal, some fiscal options are more regressive – that is, take a higher percentage as a share of income as income levels decline – than others. From that perspective, for example, as a general matter, of the four major options, cuts in Permanent Fund Dividends (PFDs) are the most regressive option, sales taxes are the next most regressive, a flat income tax is the next, and a progressive income tax – an approach that intentionally takes a higher percentage as a share of income as income levels increase – is the least.

Generally speaking, because they take more from those more likely to spend the marginal dollar (what some call the marginal propensity to consume), regressive taxes not only have the largest adverse impact on middle- and lower-income families, in the sense that they take more money out of their pockets than less regressive options, but also on the local and state economies, in the sense that they take more money from those more likely to consume than less regressive options.

For that reason, those, like us, who are mostly concerned with the impact of fiscal options on Alaska families and the state economy, usually support less regressive measures over more regressive ones.

But that isn’t the only thing going on with Alaska’s fiscal alternatives. As both the 2016 and newly published 2026 reports from the University of Alaska – Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER) on Alaska’s fiscal options discuss, the alternatives also have varying impacts on the amount of money taken out of Alaskans’ pockets, compared to the share taken from non-residents and, due to their interplay with federal income taxes, the federal government’s.

For example, while sales taxes take most of the money they raise from Alaskans’ pockets, they also take a portion from visiting non-residents who purchase Alaska goods and services while in the state. And while PFD cuts take money mostly from Alaskans’ pockets, they also draw funds from the federal government through reduced federal income taxes.

These secondary effects – the portion of the burden assumed by other than Alaskans (non-Alaskans) – generally don’t play much of a role in the relative impact of a fiscal option if all of the secondary effects fall in a fairly narrow range.

For example, if all of the options push roughly 15% – 20% of the burden to non-Alaskans, that really doesn’t significantly change the calculus of the extent to which one option takes more from middle and lower-income Alaska families or has a larger impact on the overall Alaska economy than another. The regressivity characteristics of the options still dominate the outcome.

On the other hand, if the secondary effects – the portion of the burden assumed by non-Alaskans – have a wide range, with some pushing much more to non-Alaskans than others, then they may have a significant impact on whether one option is preferable to another.

For example, assume that in attempting to raise $750 million, Option A pushes only 15% to non-Alaskans, while a second (Option B) pushes 30%, or double the first, to non-Alaskans.

Based on those numbers, while Option A would require approximately $640 million from Alaskans (roughly 85% of $750 million), Option B would require only $525 million from Alaskans (roughly 70% of $750 million), $115 million less than Option A. In that scenario, even if Option A were less regressive than Option B, because of the significantly lower level required from Alaskan families overall, Option B would still result in taking less from the pockets of an increasingly greater share of Alaska families – and through that, have a lower adverse impact on the overall Alaska economy – than Option A.

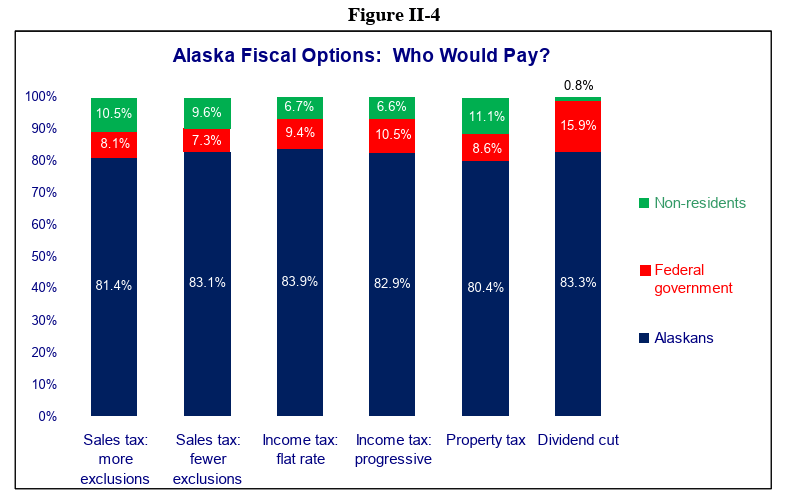

As the following chart shows, in the 2016 study, the ISER researchers found that differences in the secondary impacts across the various options fell within a fairly narrow band.

While there were differences in the split between non-residents and the federal government, the level of take from non-Alaskans generally fell within a narrow range of less than 4%, from approximately 16% to 20%, across options. The differences were small enough that they really didn’t influence the debate about which option was better for Alaskans.

However, given intervening changes in the economy, their evaluation of additional options, and other factors, the ISER researchers in the 2026 study see a significantly different landscape. Here are the slides reflecting their findings.

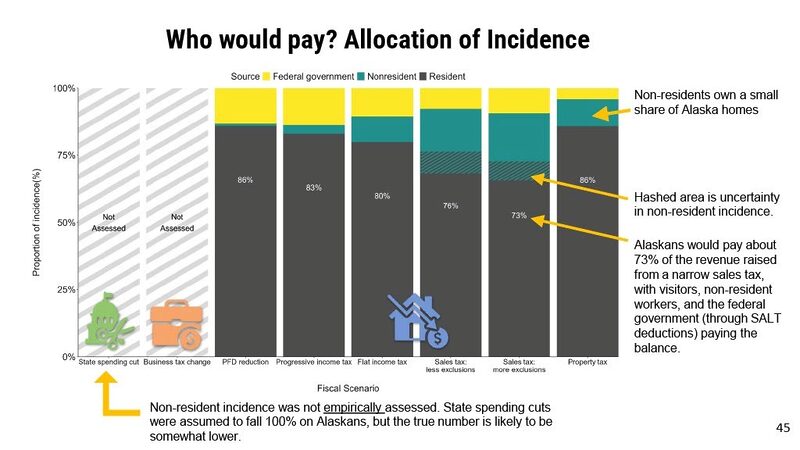

The first evaluates the four main options, with one split into two alternatives (sales tax) and one additional option (property tax):

As is clear, the amounts borne by non-Alaskans are significantly different, ranging from 14% at the low end (PFD reduction and property tax) to 27%, nearly double, at the high end (sales tax: more exclusions).

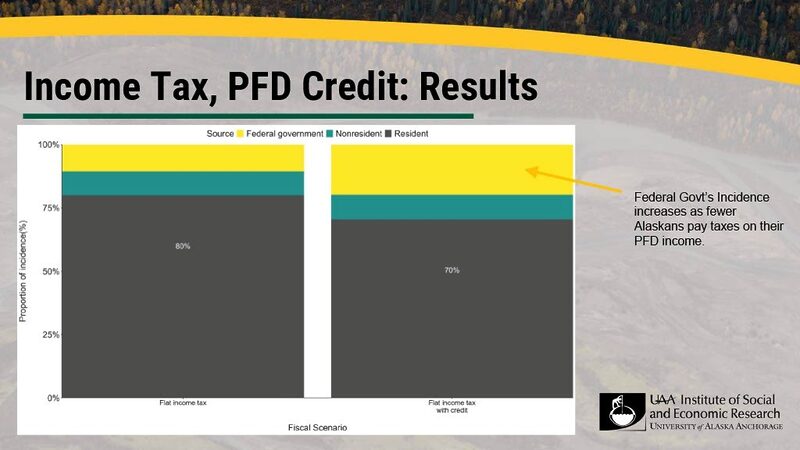

The second slide looks at two flat tax options: the first is a repeat of the one on the first slide, and the second couples the flat tax with an option to use a resident’s PFD as a credit toward the tax. By significantly increasing the share borne by the federal government through reduced federal income taxes, this additional option significantly reduces the share borne by Alaskan households.

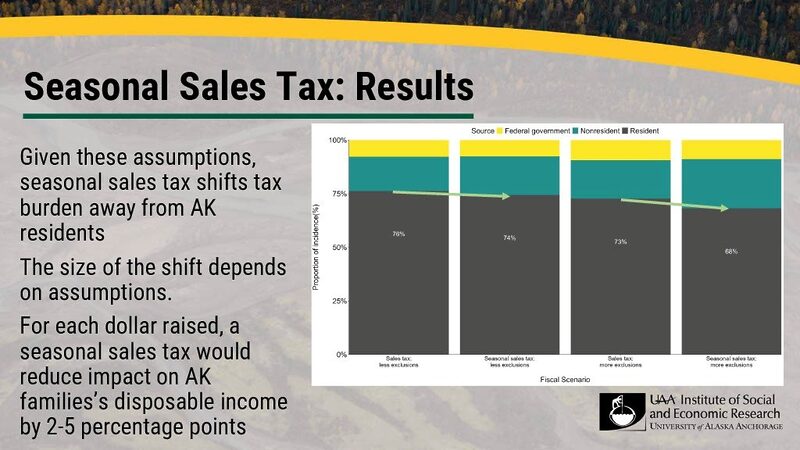

The third slide examines variations on the two sales tax alternatives from the first slide: sales tax with fewer exclusions and sales tax with more exclusions. The variations are to adjust each alternative seasonally, with higher rates in the summer, when more non-residents are in the state, and lower rates in the winter, when fewer non-residents are in the state.

Taken together, the alternatives offer a wide range in the share of any fiscal option borne by non-Alaskans, ranging from 14% (PFD cuts) at the low end to 30% (flat income tax with credits) and 32% (seasonal sales tax with more exclusions) at the high end.

At that level, the differences have a significant impact on the options. For example, again using a target revenue level of $750 million, while a progressive income tax generally may be less regressive than a sales tax, using ISER’s projections a progressive income tax would still take approximately $620 million from Alaskans (83%), while a seasonal sales tax with more exclusions would take only $510 million (68%), $110 million less. By shifting more of the burden to non-Alaskans, Alaskan households would increasingly have materially more money in their pockets, and, particularly because of the positive impact on middle-income Alaska families, the overall Alaska economy would see materially more money circulating.

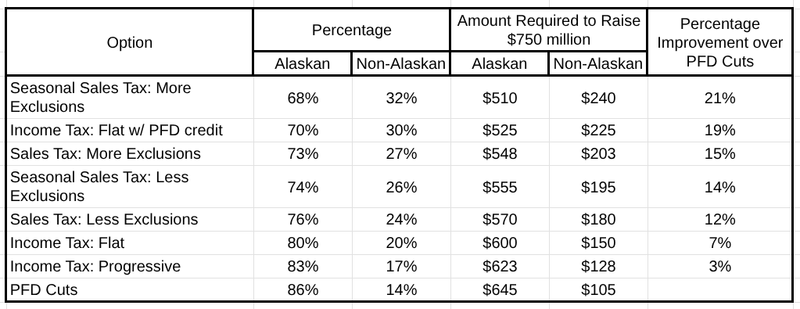

Using the $750 million mark – roughly the level proposed to be raised annually by Governor Mike Dunleavy’s (R – Alaska) seasonal sales tax – here is the breakdown between Alaskans and non-Alaskans among the various options, ranked from the lowest, in terms of overall burden on Alaskans, to the highest:

The right column measures the improvement – the additional amount that Alaskans would keep in their pockets overall – compared to using PFD cuts, the current approach used by the Legislature. At a target revenue of $750 million, Alaskans would keep $120 million, or 19%, more in their pockets with a flat income tax coupled with a PFD credit, and $135 million, or 21%, more with a seasonal sales tax with more exclusions than they do by using PFD cuts.

Overall, Alaskans would also keep nearly $100 million to $115 million, or 16% – 18%, more in their pockets using one of those two options than a progressive income tax.

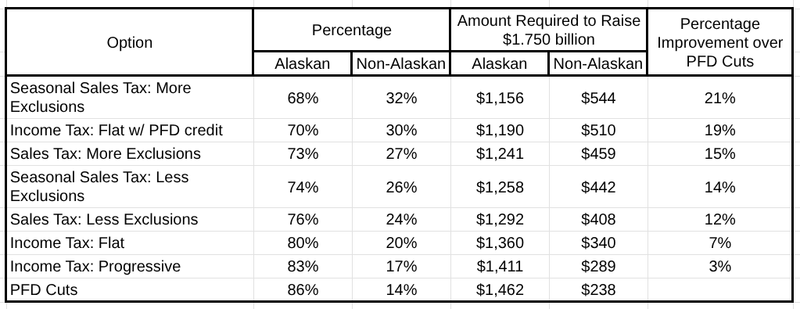

The differences grow as revenue levels increase. For example, in the current session, by cutting the PFD to $1,000, some in the Legislature effectively propose withholding and diverting nearly $1.7 billion from the statutory PFD. Here’s the impact of the Legislature raising that same amount instead through the other measures listed above:

If, instead of using PFD cuts, the Legislature raised the same amount by using a flat income tax coupled with a PFD credit, Alaskans – and through them, the Alaska economy – would keep more than an additional $250 million, a quarter of a billion dollars, in their pockets. Using a seasonal sales tax with more exclusions, Alaskans – and through them, the Alaska economy – would keep more than an additional $300 million in their pockets.

What this demonstrates is that the use of the single criterion of regressivity or progressivity isn’t a sufficient basis any longer on which to judge Alaska’s various fiscal options. Because of the significant differences, the degree to which they raise funds from Alaskans compared to non-Alaskans is also an important consideration, and, indeed, where the differences are substantial, likely a determinative criterion.

The analysis does show one thing for certain, however. Not only are PFD cuts the most regressive option – the hardest on middle and lower-income Alaska families and, through them, the overall Alaska economy – the Legislature can use, but they also take the least from non-Alaskans and, as a result of that, the most from Alaskans. For those concerned about Alaska families and the overall Alaska economy, they are the absolutely last option the Legislature should use.

One final note. We know that some will quickly say, “But what about increased oil taxes, or corporate taxes, or even spending cuts, aren’t those better?”

Our response is simple. Certainly, all of those have some role to play, but even in the aggregate, they won’t raise $1.7 billion, the level of PFD cuts some in the Legislature are proposing for this coming year. Some portion will have to be raised through personal taxes. Governor Dunleavy’s recent proposal suggests the appropriate number is around $750 million annually.

The recent ISER analysis provides huge insights into the impact of the various options in filling that role. We hope those in the Legislature will make the effort to understand and use it, rather than once again dumping the burden mostly on Alaskans, particularly middle and lower-income Alaska families.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

This discussion reminds me of a mid-nineteenth century ditty, “Don’t tax you, don’t tax me, tax the man behind the tree.” The ditty was a critique of the cynicism of political actors who try to sell some policy to an electorate based on screwing other people, not you. Is it fair to try to design policy to “screw the outsiders?”

People that come to Alaska use services and infrastructure that Alaskans help maintain.

Why should users of these services not help fund them?

I agree that tourists should pay the costs of their use of publicly provided services. But that is not what this article is trying to do. It is trying to stick outsiders with as much of the cost as possible. Keithley does nothing to try to estimate the costs that tourists impose and then charge them for that. Instead he merely wants to stick them with as much costs as possible.

Alaska has a major free-loader problem. I pay for clothes at the store. I pay for plumbing services at my house. When I use the roads, schools, and govt. services I should not have to pay? How does that make sense.

One central feature of all your articles is the assumption that regressive bad, progressive good. To this i want to put a serious question – what is the right amount of progressivity? Please try to take the question seriously. A related question is what is the right amount of inequality? Certainly we don’t want to live in a society with no inequality since there is a wide range in the value people bring to others through economic activity. Likewise, in a banana republic, where the state is enlisted to oppress the poor, inequality is too high. I think an honest,… Read more »

One final comment for now – you have never answered a question i have asked many times – why is not paying a dividend the same as taxing people hard earned money. You equate them. I take your word that ISER equates them. But i don’t think they are the same. Money that people get by working hard and creating value for others seems superior than money people get for managing to stay in AK for another year IMHO. Setting aside questions of progressivity, I don’t think it would be fair to tax money people get by doing for others… Read more »

Along these same lines, taxing while simultaneously paying a negative tax (dividend) under the banner of “regressivety” (money for the poor) is a position of welfare, regardless of how you try to run away from it. Mr. Keithley is dancing with three different partners to the same tune: he’s trying to make voters feel better about taxing by going after non-residents, trying to make them feel altruistic by keeping a PFD (even though the richest Alaskans get them, too), and trying to be Robin Hood by stealing from the rich to give to the poor. You can’t do all three,… Read more »

We are not going into debt to pay a dividend, the money is already there from earnings by the state. What matters is how that money is distributed. Is it better for the state to distribute the money to the people and let them decide how best to spend it or allow the Legislators to craft ways to distribute it to very narrow, crony entitys.

“…….We are not going into debt to pay a dividend………”

Depends on how extreme we get with this socialist “dividend solution”.

Do you consider killing a moose or catching salmon socialist? Both are provide by the state.

“……..Both are provide by the state……….”

They are managed by the state. They are not” provided” by the state. And when moose, caribou, salmon, whatever populations are down, hunting/fishing is suspended. It is not a free-for-all……despite the efforts for some to make it so just for themselves and not others. If moose, caribou, salmon, etc numbers are low, the state does not continue liberal harvest allowances and tax others to buy moose, caribou, salmon, etc from elsewhere in order to keep the harvest high.

For the best of my recollection, and I have been around since before the PFD was started, the PFD has fluctuated with the amount of funds available for distribution, as in your fish and game example, except when the Ex Governor changed it.

So, who owns the moose and fish, is it the residents or the state? I am interested in your prospective. For me there is no difference between receiving a $1000.00 check or receiving a $1000.00 worth of moose meat or fish from the state.

“……… the PFD has fluctuated with the amount of funds available for distribution, as in your fish and game example, except when the Ex Governor changed it……….” That is an incomplete explanation. In the early years, yes, the PFD amount fluctuated with the growing amount of fund returns. AS 43.23.025 provided a formula to determine the amount. Yes, former governor Bill Walker refused to sign an appropriation bill with that amount in 2016 after a painful and difficult budgetary process. Eventually, a PFD amount less than the statutory amount was proposed that he signed. Senator Bill Wielechowski sued. The Alaska Supreme… Read more »

“……..Is it better for the state to distribute the money to the people and let them decide how best to spend it or allow the Legislators to craft ways to distribute it……”

Yet again, in Wielechowski v Alaska, the Supreme Court ruled that appropriations must go through the legislative process. Period. Your opinion on how best to spend state money or who owns it is completely irrelevant.

The State of Alaska is an owner state. The people are the state. The state is not a separate entity. Money that comes to the state belongs to the people. The PFD is a dividend distributed to the people from earnings of the state. We do no physical labor for the PFD just as we do no physical labor for interest received from interest bearing bank accounts or profits earned on stock investments. It is still your money, no sweat required.

“……..The State of Alaska is an owner state………”

Please define “owner state” and quote and cite any words in Alaska’s Constitution which supports that statement and your interpretation, please.

The Alaska Constitution established that natural resources are held in trust for the common use of all Alaskans. My interpretation is, owned by the residents.

Article 8, Section 1: “……..It is the policy of the State to encourage the settlement of ITS land and the development of ITS resources by making them available for maximum use consistent with the public interest……….” The land and resources are clearly delineated as owned by THE STATE, not “the residents”. And “maximum use consistent with the public interest” does not equate to a free-for-all. The Supreme Court ruled in Wielechowski v. Alaska that the dividend is an appropriation like all others and is subject to the appropriation process. Therefore, if the Legislature decides that the dividend should be $10,000… Read more »

You nailed it Reggie, good job.

A “State” is nothing more than an organizational frame work used in managing human affairs.

.

Yes, and the State of Alaska is the organizational framework we’ve used to manage Alaska’s resources.

You’re just arguing in circles.

Now get out there and steal a trooper cruiser! I mean, it’s yours, right?

“………A “State” is nothing more than an organizational frame work used in managing human affairs………..”

Yes. Constitutionally. And glib themes don’t cut it. The precise wording of the Constitution is what reigns. “Owner state” has no meaning. It’s socialist code.

Your reply does not address at all the question of why we should tax people just to pay a dividend. To widen the argument i have made before: If i work, i am doing something for someone else to get my wage. When i loan money to a bank to get interest, i am doing something that the bank wants. When i buy a stock to get a dividend, i am giving the seller of that stock money. In all these cases, i am doing something someone else wants me to do to get the money. To get a PFD,… Read more »

Dividends, stock sales and interest income is passive income, no labor required.

Yes, but you have to do something for someone else to get dividends and interest. You don’t need to do anything for anyone else to get a PFD, you just need to stick around for another year.