The typical flurry of legislative session op-eds warning against changes to oil taxes began the week before last. True to form, the season kicked off with an op-ed in the Anchorage Daily News (ADN) by the Co-Chairs of “Keep Alaska Competitive,” Joe Schierhorn and Jim Jansen. This was followed by a solo op-ed, also in the ADN, from Representative DeLena Johnson (R – Palmer), and shortly thereafter, another co-signed by fifteen of the nineteen members of the Republican House minority, along with Representative Chuck Kopp (R – Anchorage), the House majority leader.

The op-eds predominantly relied on two arguments. As argued by Schierhorn and Jansen, the first is that “over the next five or so years, new production will generate significant new revenue for state and local governments.” The second, which is a more modest claim than that of Schierhorn and Jansen, is that proposed legislation this session that modifies the current tax structure would “raise taxes.”

Neither is true.

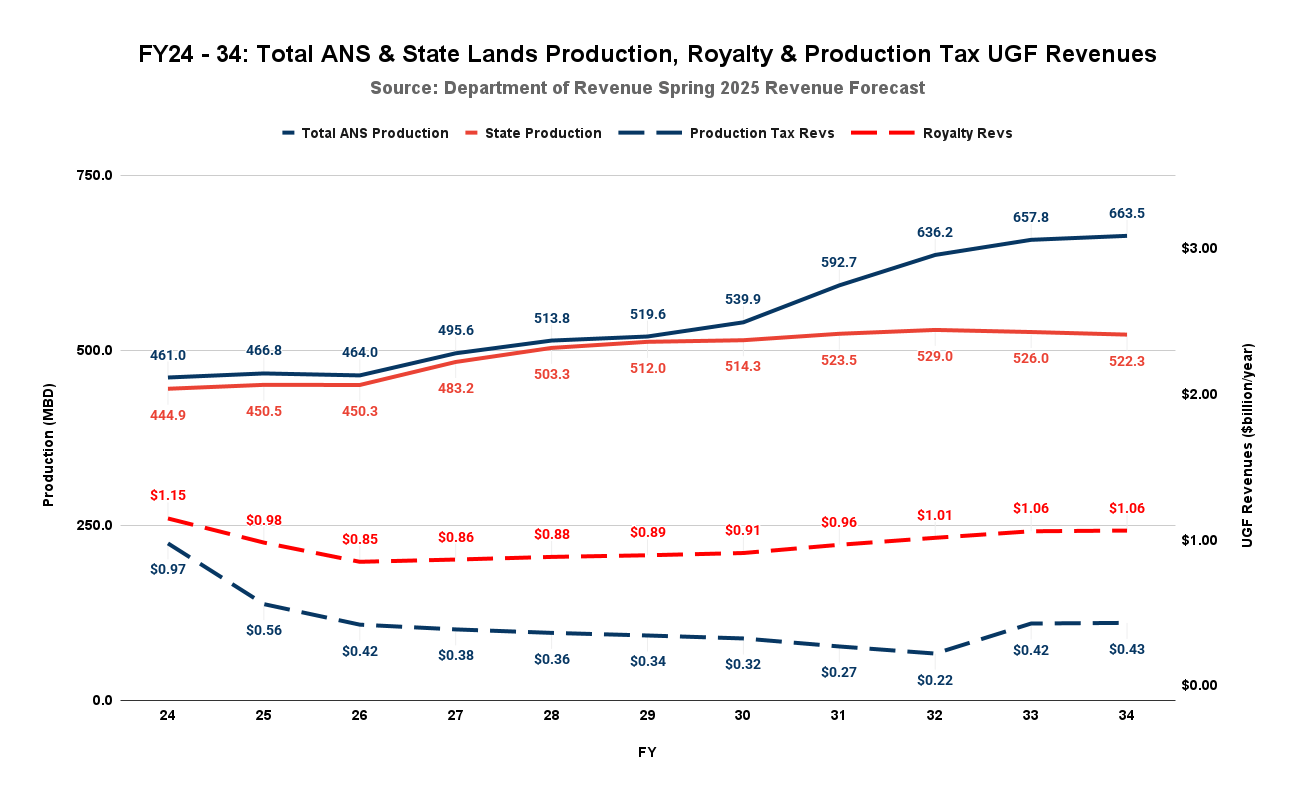

The first isn’t even remotely accurate. Below are the projected production figures and related unrestricted general fund (UGF) revenues for the next ten years, as outlined in the Department of Revenue’s (DOR) Spring 2025 Revenue Forecast released earlier this month. The lines at the top represent the projected production numbers. The solid blue line indicates the overall production figure projected by DOR. The solid red line represents the projected production from state lands, derived by subtracting DOR’s projected volumes from the federal National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPRA) from DOR’s overall production estimates.

The dashed lines at the bottom represent the projected revenue numbers related to production from royalties and production taxes. The dashed red line indicates projected UGF royalties, while the dashed blue line represents projected production taxes. Royalties are earned only on production from state lands, whereas production taxes are collected on production from both federal and state lands.

At no time during the entire period do the combined revenues from production ever rise above the FY24 baseline. The closest they come is in FY25 when they reach 72.5% of FY24 levels. Five years out (FY29), the timeframe used by Schierhorn and Jansen, they are only at 58.3% of FY24 levels. From there, they decline even further to 58.1% of FY24 levels before recovering back to 70.4% in FY34.

Schierhorn and Jansen’s assertion that “over the next five years or so, new production will generate significant new revenue” is a patent falsehood. Apparently, the ADN no longer bothers to fact-check the op-eds it publishes.

The claim made in the op-eds by the legislators that the legislation proposed this session, which modifies the current tax structure, would “raise taxes” is more nuanced. It rests on the argument that the nominal tax rates resulting from the proposed legislation would be higher. However, SB21 – the shorthand name for the current oil tax code – is an exceedingly complex mixture of tax rates, deductions, credits, and “reductions.” Just because the nominal tax rates are higher doesn’t necessarily mean that the effective tax rates incurred by producers will also be higher.

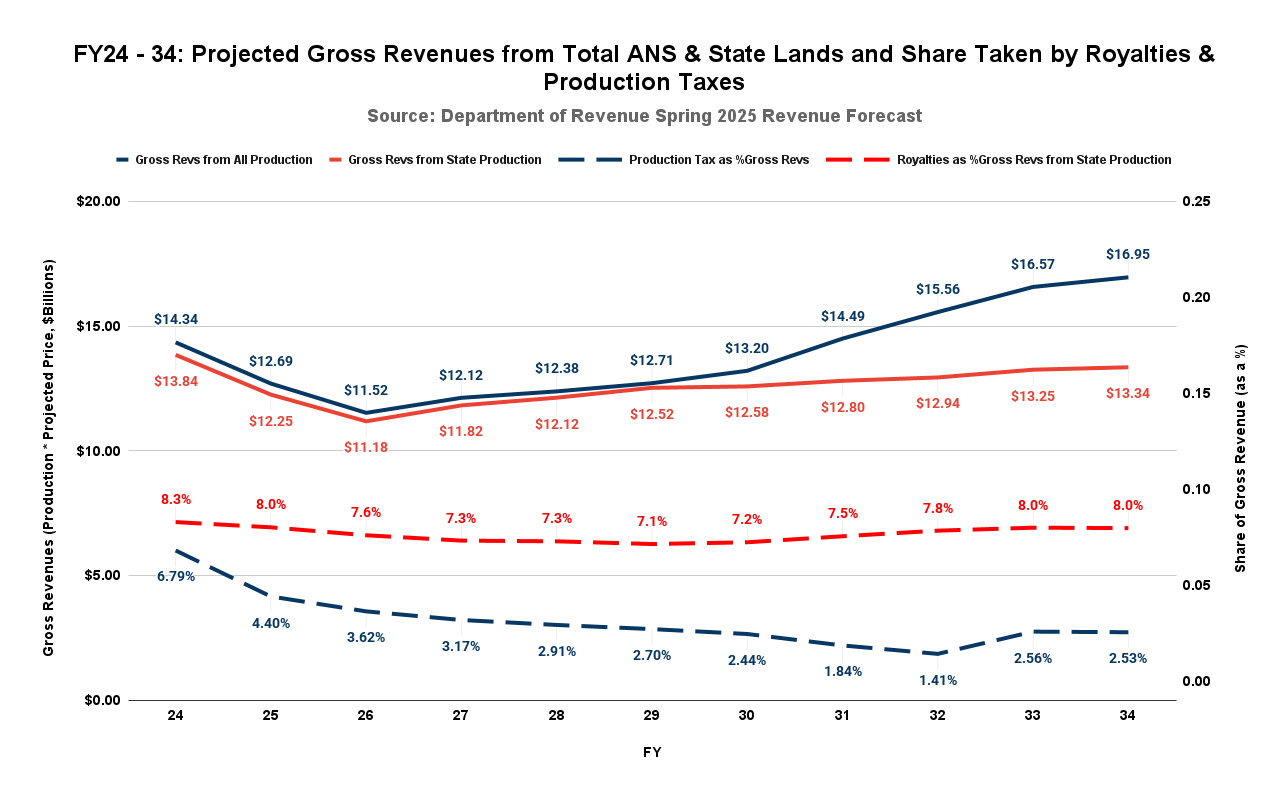

Analysts frequently examine the impact of a tax structure on gross revenues when comparing various approaches or assessing the overall consequences of changes to any specific oil tax structure. This method automatically considers variations in prices and production volumes, ultimately focusing on how much of the gross revenues received by producers are taken by the government.

Analyzing the impact of changes on gross revenues serves as a valuable analytical tool because it bypasses the disputes and complexities often associated with producer costs. Our use of this tool in this context does not imply that Alaska’s oil tax structure should be changed to rely solely on gross revenues. Adjustments for costs, credits, and other factors are frequently beneficial in shaping a tax structure that incentivizes or penalizes certain actions within a broader revenue framework.

However, examining the impact on gross revenues provides crucial insight into the overall effects of an approach – whether it ultimately extracts more revenues from producers or less, or, in other words, increases taxes, maintains them, or reduces them. This method allows us to see the overall “forest” without getting bogged down in the “trees” of the various components.

The following chart addresses this issue by calculating the percentage of total gross revenues generated from royalties and production taxes – the revenue sources directly linked to production levels – over the same ten-year period as the earlier chart. We calculated total gross revenues simply, by multiplying projected prices by production volumes. Since royalties are sourced only from state lands, while tax revenues are derived from overall production on both state and federal lands, we computed gross revenues separately for total production and production from state lands.

The percentages are calculated by dividing the projected revenues for each category (royalties and taxes) in DOR’s forecast by the relevant gross revenue. The results are highly enlightening.

While royalties remain at a relatively stable percentage of gross revenues from state lands throughout the period, the percentage of revenues received through production taxes declines substantially, from 6.79% of overall gross revenues in the FY24 base year to 1.41% by FY32, before partially readjusting upward to approximately 2.55% in the final two years of the forecast.

The difference is significant. Using the “five-year” test suggested by Schierhorn and Jansen as an example, by FY29, the share of gross revenues received by the state declines to 2.7%, producing $342.6 million in production tax compared to the $863 million in production taxes the state would be projected to receive if the percentage of gross revenues had remained at the FY24 baseline of 6.79%. That’s a one-year difference of $520 million.

By FY32, when the share of gross revenues received by the state through production taxes is projected to decline to 1.41%, the one-year difference has grown to $838 million: $220 million projected versus $1.056 billion at 6.79%. As the share of gross revenues the state receives increases to approximately 2.55% by the end of the 10-year period, the difference declines somewhat to roughly $710 million.

Over the 10-year period, the average annual impact – the difference between the projected production tax revenue and what it would have been if the percentage of gross revenues had stayed at the baseline of 6.79% – is approximately $566 million.

In summary, throughout the 10-year forecast period, SB21 is generating significantly less in production taxes than the FY24 base year and also a smaller share of gross revenue than that year. This strongly suggests that something has gone wrong with what was intended to be a stable tax structure for both producers and the state.

The relationship between production and production tax revenues during this period is even more crucial. SB 21 was presented to the public in the early 2010s when it was passed and subsequently defended in the 2014 referendum as a means to stimulate investment in the state and, consequently, increase production. The argument was that while the previous ACES (Alaska’s Clear and Equitable Share) tax approach raised more state revenue in the short term, upstream investment and production were in rapid decline. The premise was that by restructuring taxes as proposed by SB21, upstream investment and production would increase, and as production rose, Alaskans would benefit through higher revenues from royalties and production taxes.

However, as the first chart in this column clearly illustrates, this is not expected to occur over the next decade. In fact, the projection is the opposite. Overall production in the 10-year period is projected to rise by an impressive 44%. Yet, production taxes are not anticipated to increase at that rate or even a fraction of it.

Instead, production taxes during this period are projected to decline by 56%.

Pause to reflect on this: annual production is expected to increase by over 44% during this timeframe, while yearly production taxes are projected to drop by over 56%. Given the statements made in 2014, defending the current situation as attempted in the op-eds of Schierhorn, Jansen, and the Republican legislators is demonstrably laughable.

To be honest, while we fully support SB 92 – the proposed fix to the “Hilcorp Loophole” discussed in previous columns – we are not as enthusiastic about SB 112, the other oil tax-related bill criticized in the op-ed by some House Republicans.

It’s not that we believe reforming the state’s oil production tax structure is wrong; indeed, it’s imperative for the reasons explained above. However, we think SB 112’s approach is too simplistic.

As explained in a previous column, several provisions in SB21 contribute to the decline in production revenues over the next decade. It’s not only the often-criticized per-barrel credit that’s problematic; various other factors, such as the amortization period used to recover capital costs and the significant revenue reductions caused by the provision for “gross value reductions,” also play a role. To truly – and fairly, since different producers are affected differently by various provisions – address the issue, we believe all three contributors (and perhaps more) need to be considered in balance.

However, if it’s the only option available, SB 112 in its current form is acceptable. While a finely tuned scalpel would be much more effective in this situation than a somewhat misdirected sledgehammer, the problem is so severe that even a simplistic solution is preferable to allowing the current situation to persist.

SB 21 is broken, and Alaskans are being left to pay for the financial gaps it creates through deeper and deeper cuts in their Permanent Fund Dividends. As promised when it was passed, Alaskans are entitled to benefit alongside the increasing production volumes and producer revenues. The relationship must be restored.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Sockeye 2 is on state land.

https://investor.apacorp.com/news-releases/news-release-details/apa-corporation-and-partners-lagniappe-alaska-and-oil-search

SB21 was broken the moment Parnell added the $8/bbl tax giveaway. I’ve been saying that for many years.

As has Weilechowski. Agreed. We’ve almost always been the oil companies’ bitches, except for the few years ACES was in effect. And don’t even get me started on mining, an industry Alaska taxes almost not at all.

Thank you, Brad, for another cogent and insightful analysis.