In last week’s column, we spent time looking at the recent analyses by the Department of Revenue (DOR) of the projected 25-year fiscal impacts separately of Conoco’s Willow Project and Santos’ Pikka Project. Most of our focus was spent on analyzing the point at which some, and then, ultimately, full production taxes would be paid on production from each project.

As we explained there, according to DOR’s analysis, the Pikka project is currently projected to go for the first seven years with paying only a limited amount of production taxes (entirely on the minor “Landowner Royalty Interest” share), then spend another five years paying only the minimum production tax, before finally, in year 13 of the project – and after roughly 75% of the projected oil has been produced – it begins to pay full production taxes. The Willow project is currently projected to begin paying the minimum production tax from the start of production, and to remain on minimums for the entire remainder of the production curve.

In this week’s column, we dive deeper into the numbers to look at the projected average annual revenue impact across periods of time: the period from first production through Fiscal Year (FY) 2033, then the period from FY2034 through FY2043, then finally the period from FY2044 through FY2053. As we have noted in previous columns, production tax revenues are projected to decline significantly from baseline (FY2024) levels over the current budget projection period, through FY2034. We use DOR’s analysis of the Willow and Pikka projects to gain insight into whether the decline in production tax revenues “turns around,” as some have claimed, or, instead, the decline continues beyond that point into the future.

We focus on production taxes because, historically, they have been one of the most significant sources of unrestricted general funds (UGF) in Alaska’s budget from oil production. While oil royalties are also substantial, over the five-year period from FY2020 through FY2024, average annual UGF revenues from production taxes were nearly equal to those from royalties ($985 million v. $990 million).

Going forward, production taxes are anticipated by many to play an even more important role in Alaska’s fiscal outlook. While the fact may change over the longer run as a result of some provisions in the recent federal “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” at least for the foreseeable future, the state will likely receive little to no royalty revenues from production from federal lands. As production from those lands becomes an increasingly larger segment of overall output, the state will need to rely heavily on production taxes to provide a stable state revenue base. Because Alaska cannot enact a production tax system that would be discriminatory against production from federal lands, the tax rates that produce reliable revenues from federal lands will need to apply equally to production from state lands.

While not a comprehensive review, DOR’s analyses of the Willow and Pikka projects provide valuable insights into future state oil revenue and production tax levels. Using the DOR’s most recent production forecasts contained in its Spring 2025 Revenue Forecast, Willow and Pikka combined represent roughly 42% of projected FY2034 production from all sources. If production taxes from those sources aren’t on track to match or exceed historic levels in the years following, it is unlikely that production taxes overall will meet the objective of providing a significant source of state revenue.

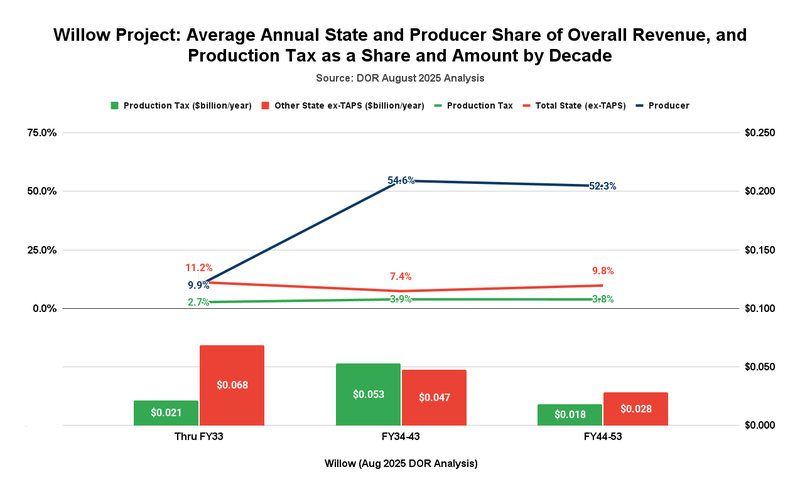

Here is what DOR’s analysis tells us with respect to production from the Willow project:

While NPRA (mainly, Willow) is projected to supply more than 20% of total Alaska production by FY2034, production taxes from the project are projected to average only $21 million per year, or less than 5% of total overall production taxes during the same timeframe. Total projected state revenues from the project are projected to average only $89 million per year, which is also less than 5% of total overall unrestricted petroleum revenue for the same period.

As shown on the chart, during that period, those amount to only 2.7% (production tax) and 11.2% (overall state revenues) of total project revenues, respectively. Because of the heavy front-end impact of federal royalties, during the same period, the producer’s share only amounts to 9.9% of overall project revenues.

The producer share changes rapidly over the subsequent ten years, however, rising from 9.9% of total project revenues to over 50%. On the other hand, while production taxes as a share of total project revenues rise slightly, from 2.7% to 3.9%, overall state revenues as a share of total revenues actually decline, from 11.2% to 7.4%. While the nominal level of projected annual average state revenues rises slightly over the period to $100 million, the growth does not even keep pace with projected inflation. In real dollar terms, annual UGF state revenues from Willow, already relatively minor in the first period, decline even further over the next.

That decline continues in the third period. While overall state revenues as a share of total revenues increase slightly, from 7.4% to 9.8%, the nominal level falls to an annual average of $46 million due to declining production levels. The producer’s share of overall revenues remains elevated at more than 50%.

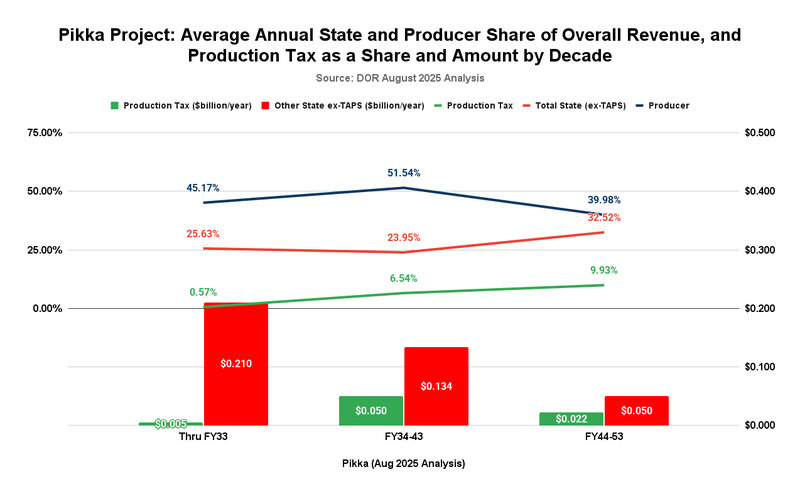

At first blush, overall state revenues from the Pikka project appear more favorable than those from Willow because the numbers include oil royalties.

Like NPRA, the area classified as “Other” in DOR’s Spring 2025 Revenue Forecast is projected to supply more than 20% of total Alaska production by FY2034. But production taxes from the project are projected to average only $5 million per year, or around 1%, of total overall production taxes during the same timeframe. That is even less than the amount and level projected from Willow over the same period.

While the level of production taxes as a share of total project revenues derived from Pikka climbs during the second period to 6.5%, the nominal average annual amount remains only $50 million, less than that from Willow. Slightly mixing time periods, while Willow and Pikka combined represent over 40% of production by FY2034, in the decade following, combined annual average production taxes from both generate less than 25% of FY2034’s already depressed level of production taxes, and only slightly over 10% above the FY2024 baseline level in nominal dollars.

In short, over the decade following FY2034, the Willow and Pikka analyses strongly suggest that production tax levels are likely to decline further, rather than stabilize at the already depressed levels projected in DOR’s Spring 2025 Revenue Forecast, much less recover even to the nominal levels reflected in the FY2024 baseline. The claim by some that more production means more revenue for the state doesn’t pan out. As production from federal lands becomes an increasingly larger share of the overall mix, and new production, generating lower production taxes, replaces current production sources, state revenues from oil production continue to decline.

That decline continues in the third period, from FY2044 to FY2053. While production tax revenues as a share of total revenues from Pikka increase from 6.5% to 9.9%, the nominal level falls to an annual average of $22 million. The decline in production levels during the third period more than offset the increase in the percentage level of take.

The resulting takeaway is that while some are looking to oil production taxes to return to providing a significant share of Alaska state revenue in the years beyond the current revenue forecast, DOR’s recent Willow and Pikka analyses suggest that they will not. Indeed, the studies indicate that revenue from production taxes will continue to decline, reaching a point where, at least under the current production tax system, they provide only a minor portion of Alaska’s revenue stream.

That is especially bad news for the state’s revenue outlook as non-state royalty-bearing production from federal lands becomes an increasingly large part of the overall production mix. At least under the state’s current production tax system, the claim by some that increased production tax receipts will help fill the gap rings hollow.

If they aren’t already aware, DOR’s Willow and Pikka analyses should serve as a wake-up call for those responsible for crafting Alaska’s fiscal future. Looking ahead, the current structure of the state’s production tax system not only fails to stabilize state revenues at current, depressed levels, but it also leads to continued and significant declines.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Alaska needs to secede from the US and nationalize its oil and gas.

You might want to wait and see what the U.S. does to California first when they try it. I have a feeling it will go better for the U.S. than the Russians are doing in Ukraine.

Important insight! The chart clearly shows that oil tax revenues aren’t rebounding, highlighting the challenges Alaska faces for stable state funding.

snow rider

It’s fascinating to see the projected revenue impacts analyzed across different time periods. The detailed breakdown of when full production taxes kick in for each project sheds light on the long-term financial implications. This deep dive into the numbers offers valuable insights into the oil industry’s doodle baseball