As we approach the end of this year’s regular legislative session, legislative leadership is increasingly talking about the need for “compromise” to resolve the significant differences between the Senate and House both on a long-term fiscal plan and, as of the time we are writing this week’s column, even the FY24 budget.

As other issues are agreed, the discussion has increasingly focused on the level of cuts to be made in the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) distributed to Alaska families.

Because the Legislative Finance Division (LFD) consistently has failed to do so, this week, we look at the impact of some of these “compromise” positions on Alaska families.

As we’ve expressed before, it is difficult for us to understand why the Senate and House Finance (or, for that matter, the House Ways & Means) Committees fail to request such an analysis from LFD of every significant fiscal approach they consider. Every other state legislature we look to for ideas on fiscal policy makes such an analysis a routine – and critical – part of their process.

In Alaska, however, all that LFD analyzes is how the various approaches impact the ability of the state to balance its budget overall. Those on the various committees considering the alternatives – both Republicans and Democrats – seem intentionally to want to remain clueless about how the various alternatives for doing so impact Alaska families and, through them, the Alaska economy.

It’s as if they are only concerned about the government’s fiscal condition, not how the various alternatives also impact the fiscal condition of the actual Alaska families whom they purport to represent.

Moreover, the desire for ignorance is not confined to the Legislature. The Department of Revenue (DOR) and the Dunleavy administration’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) – both of which can perform the analysis themselves – have remained silent on the issue.

This failure at the executive level is even more striking given what Governor Mike Dunleavy (R – Alaska) himself said recently about the goal of fiscal policy: “A broad-based solution that doesn’t gouge or take huge parts from one sector or another, or penalize one sector or another, is probably the most important thing we can do.”

How does Dunleavy know if they are achieving that “most important” objective if his administration doesn’t analyze the impact of the proposals they are considering on the various “sectors”?

Even if neither the leadership of the various legislative committees nor the governor care about the impact of their policies on the actual Alaska families whom they purport to represent, however, we – and we suspect, some individual legislators, and we know, many Alaska families – do. This analysis is for them.

Baseline. The threshold question of any such analysis is what baseline to use. When looking at “compromise” proposals, that question translates into “compromise from what.” Because it is current law, we use the statutory Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) as the baseline for purposes of the following. The impact we calculate is the difference between the proposed “compromise” position and current law.

As Senator Bert Stedman (R – Sitka), one of the finance co-chairs, is quick to point out, without more, several of the compromise positions still result in budget deficits.

At least for purposes of the FY24 budget, the House proposes to address those by further drawing down savings – essentially, taxing future Alaskans.

The Senate, on the other hand, uses that as a justification for raising revenues through even deeper PFD cuts – an approach which, as University of Alaska – Anchorage Institute of Social and Economic Policy (ISER) Professor Dr. Matthew Berman recently put it, is the “most regressive tax ever proposed.”

In the following, we fill any remaining deficit through a distributionally neutral flat tax. If, as Governor Dunleavy said, the most important goal of any proposed solution is to avoid taking more (“gouging” or “penalizing”) from one sector than others, a distributionally neutral flat tax on this generation – the ones incurring the deficits – offers the best approach.

For purposes of calculating the size of the fiscal hole the parties are trying to address, we add the $1.3 billion included in the Senate’s version of SB 107, which Senator Stedman claims is necessary to address both current and future deficits at POMV (percent of market value) 50/50, to $620 million, the average difference over the same period between the current law PFD and that resulting from POMV 50/50. Based on Senator Stedman’s numbers, the resulting $1.9 billion is the amount required to balance the budget on an ongoing basis under current law.

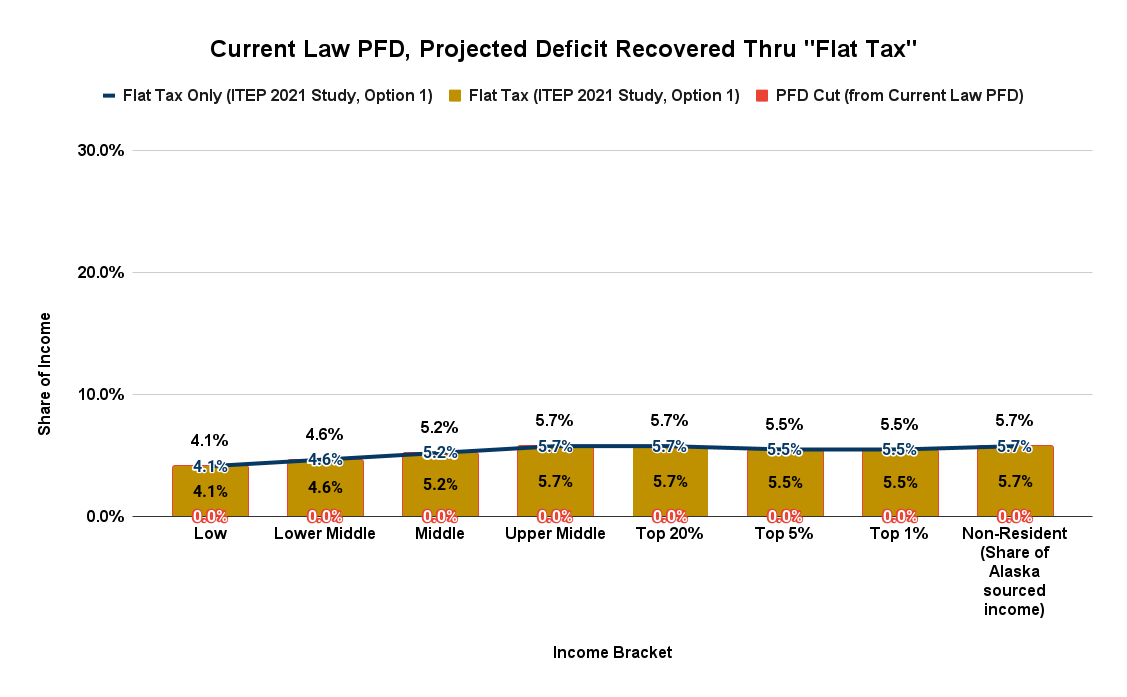

Here is the impact of retaining the PFD at current law levels – the baseline – and closing the $1.9 billion annual deficit instead through a distributionally neutral flat tax.

In this base case, all income brackets contribute relatively equally as a share of income toward closing the deficit. As importantly, by using a broad-based approach, non-residents receiving a portion of their income from Alaska sources contribute as well, reducing the overall burden on Alaska families by what ISER estimates at roughly 7%.

Alternatives. As alternative compromises, we analyze the impact on Alaska families of using POMV 50/50, POMV 40/60, POMV 30/70, and POMV 25/75.

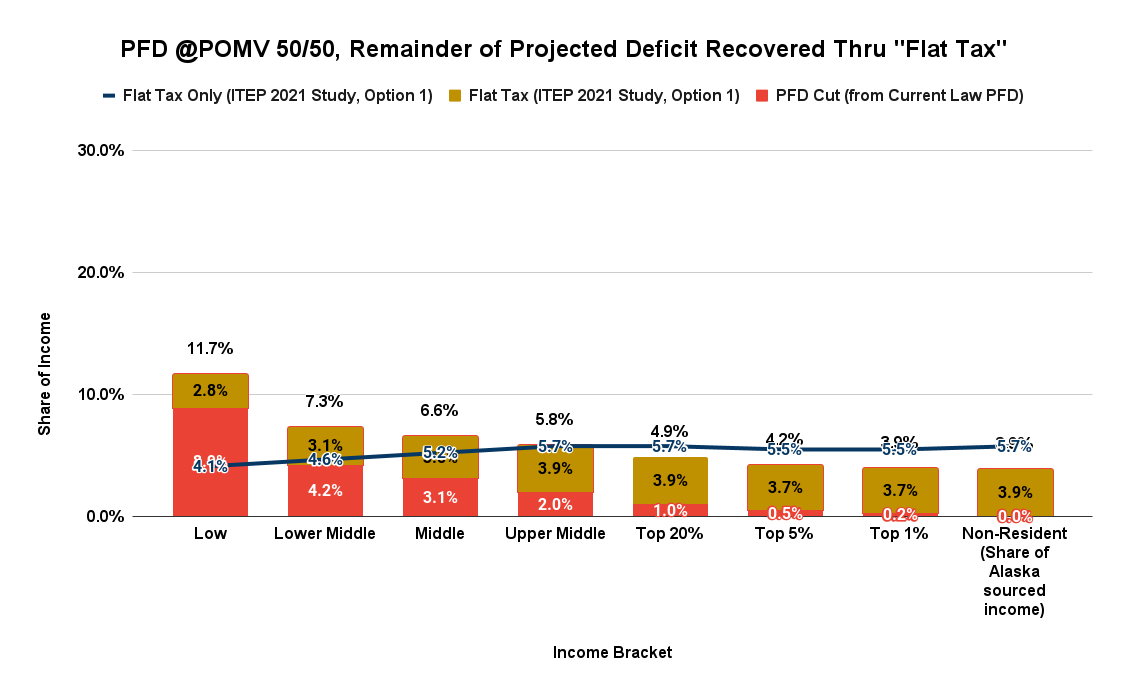

Here is the impact of reducing the PFD to POMV 50/50, which would raise $620 million from PFD cuts and close the remaining $1.3 billion annual deficit through a distributionally neutral flat tax.

As will be repeated throughout, the effect of the “compromise” is to lower the impact of closing the deficit on non-residents and the top 20% as a share of income, in this case from 5.7% to 4.9% (top 20%) and 3.9% (non-residents).

On the other hand, the effect on every other income bracket – in total, 80% of Alaska families – is to increase the share of income being diverted to government from the distributionally neutral baseline. Using POMV 50/50, the impact on upper-middle income Alaska families rises from 5.7% to 5.8%, on middle-income Alaska families from 5.2% to 6.6%, on lower-middle income Alaska families from 4.6% to 7.3%, and on the lowest 20% of Alaska families from 4.1% to 11.7%.

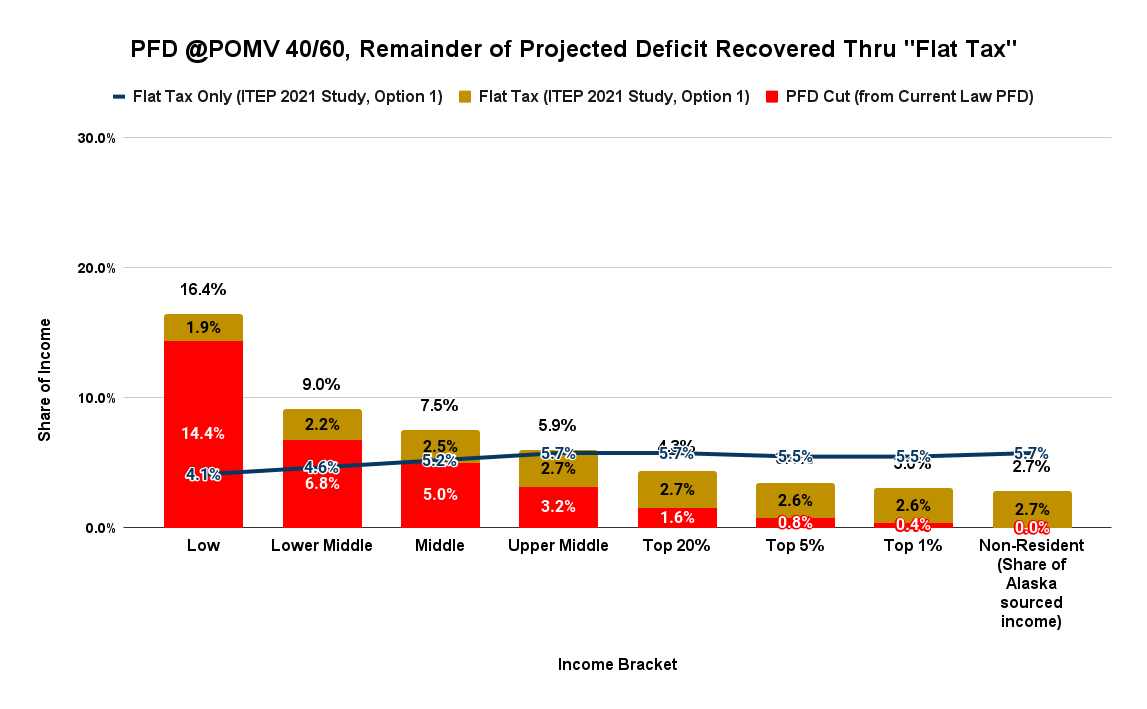

Next is the impact of reducing the PFD to POMV 40/60, which would raise $1 billion from PFD cuts and close the remaining $900 million annual deficit through a distributionally neutral flat tax.

Again, the effect of the “compromise” is to lower the impact of closing the deficit on non-residents and the top 20% as a share of income. The reduction is even more dramatic than under POMV 50/50. This time the level of take from the top 20% is reduced from 5.7% to 4.3%, and the level of take from non-residents is reduced from 5.7% to 2.7%.

On the other hand, the effect on every other income bracket – in total, 80% of Alaska families – is to increase the share of income being diverted to government. The impact on upper-middle income Alaska families rises from 5.7% to 5.9%, on middle-income Alaska families from 5.2% to 7.5%, on lower-middle income Alaska families from 4.6% to 9%, and on the lowest 20% of Alaska families from 4.1% to 16.4%.

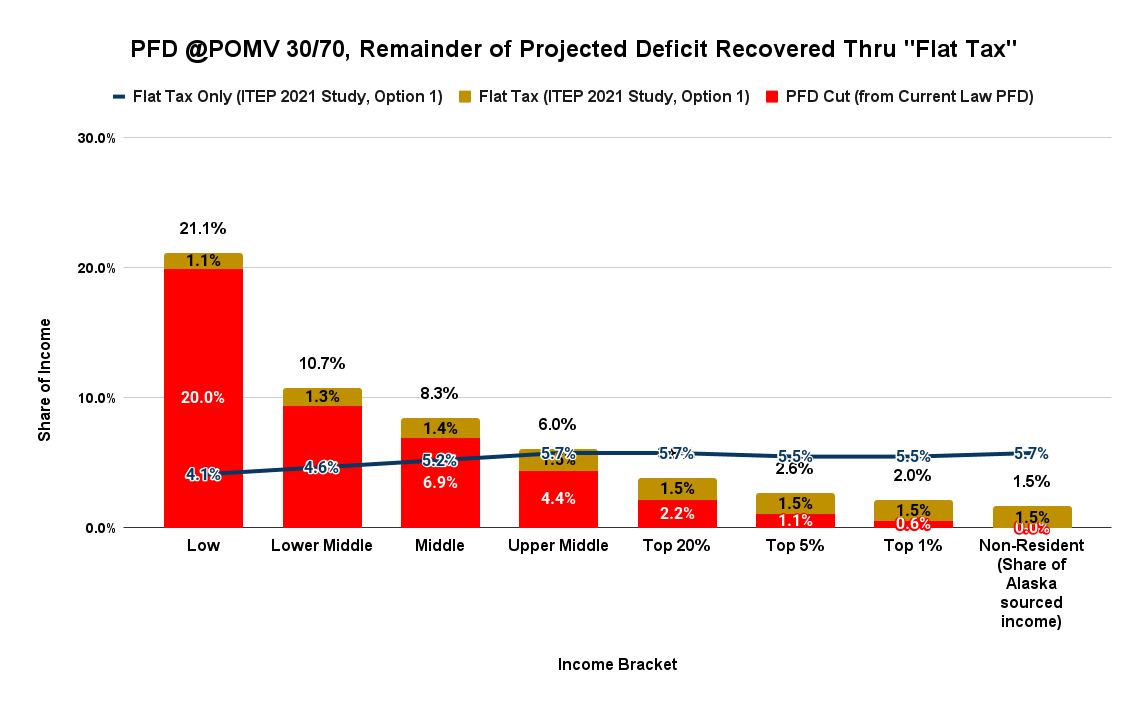

Next is the impact of reducing the PFD to POMV 30/70, which would raise $1.4 billion from PFD cuts and close the remaining $500 million annual deficit through a distributionally neutral flat tax.

As before, the effect of the “compromise” is to lower the impact of closing the deficit on non-residents and the top 20% even further as a share of income. This time the level of take from the top 20% is reduced from 5.7% to 3.7%, and the level of take from non-residents is reduced from 5.7% to 1.5%.

On the other hand, the effect on every other income bracket – in total, 80% of Alaska families – is to increase the share of income being diverted to government. The impact on upper-middle income Alaska families rises from 5.7% to 6%, on middle-income Alaska families from 5.2% to 8.3%, on lower-middle income Alaska families from 4.6% to 10.7%, and on the lowest 20% of Alaska families from 4.1% to 21.1%.

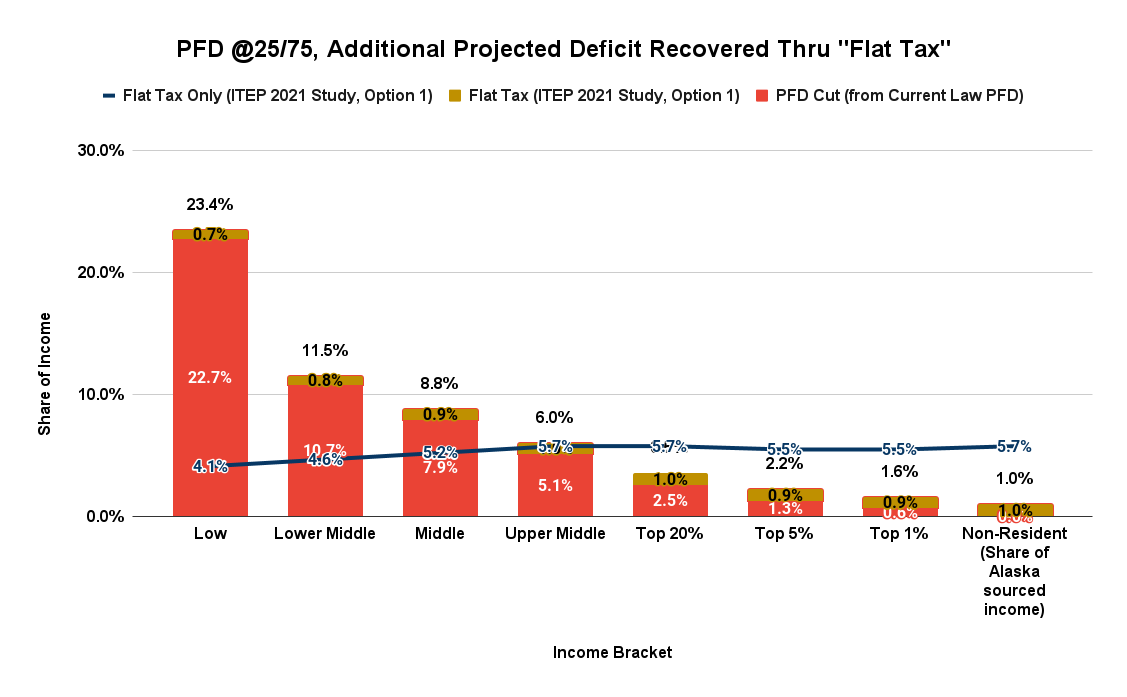

Finally, the impact of reducing the PFD to POMV 25/75 would raise $1.6 billion and close the remaining $300 million annual deficit through a distributionally neutral flat tax.

As before, the effect of the “compromise” is to lower the impact of closing the deficit on non-residents and the top 20% even further as a share of income. This time the level of take from the top 20% is reduced from 5.7% to 3.5%, and the level of take from non-residents is reduced from 5.7% to 1%.

On the other hand, the effect on every other income bracket – in total, 80% of Alaska families – is to increase the share of income being diverted to government. The impact on upper-middle income Alaska families rises from 5.7% to 6%, on middle-income Alaska families from 5.2% to 8.8%, on lower-middle income Alaska families from 4.6% to 11.5%, and on the lowest 20% of Alaska families from 4.1% to 23.4%.

As is clear, the impact throughout of such an approach to “compromise” is to lower the impact of the deficits on the top 20% and non-residents while increasing it on the remaining 80% of Alaska families.

Applying Governor Dunleavy’s “most important” test, at every step, the proposed “compromises” are increasing the extent to which one sector – the other 80% – is being disproportionately “gouged” or “penalized,” not decreasing it.

From the perspective of Alaska families, the outcomes are the exact opposite of the definition of compromise, where “settlement of a dispute is reached by each side making concessions.”

Here, the top 20% and non-residents consistently gain from any so-called “compromise.” Only the remaining 80% of Alaska families are required to make concessions.

From the perspective of the top 20% and non-residents, all of the so-called “compromise” options are the equivalent of “heads I win, tails you lose.”

Conversely, from the perspective of the remaining 80% of Alaska families, all of the so-called “compromise” options are the equivalent of “heads I lose, tails I lose even more.”

One other type of proposed “compromise” has the same effect.

As passed by the Senate, SB 107 contemplates that the level of PFD cuts will be reduced – the PFD will increase – if prescribed levels of new revenue and increased savings are achieved by a date certain.

But that path is illusory.

If SB 107 were to pass in the Senate’s proposed form, those in the top 20% would have no incentive subsequently to support any such increases either on themselves or on those, such as the oil industry, with whom they are aligned. Instead, their incentive would be consistently to oppose any such efforts.

They would already have achieved all that they wanted – a budget fully balanced on the backs of the remaining 80% of Alaska families. There would only be downside to them from adopting any alternative revenues.

As such, the proposed mechanism isn’t a real compromise. It’s just a smokescreen designed to obscure what’s really going on. The top 20% lock in their objective; the other 80% have no realistic path to offsetting the impact on them.

While some might continue to talk about alternative revenues to maintain the charade for a while longer, nothing would ever come from it.

Frankly, if these are the types of compromise those in the Legislature who claim to prioritize “working (middle & lower income) Alaska families” have in mind, it’s time for someone else to take their place. They are just digging the hole for their constituents deeper and deeper.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

“Every other state legislature we look to for ideas on fiscal policy makes such an analysis a routine – and critical – part of their process.” Thank you for highlighting this. Our state government has pumped billions of dollars into the economy over the years without a comprehensive understanding of the economic impact. How much does the PFD actually cost us? Because when it comes out, at least in Anchorage, DV goes up, child abuse goes up (reports to OCS), and student attendance drops (data is shared every year). Maybe the PFD makes sense; maybe it doesn’t. As a baseline for… Read more »