In last week’s column, we compared nominal growth in Alaska’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to “real” (ex-inflation) Alaska GDP growth since 2000, and then compared real GDP growth to the “growth” over the same period in real median Alaska household income.

We did that because, as we noted at the beginning of the column, some observers routinely base their assessment of the economic health of the Alaskan economy, including that of Alaskan households, on the level of growth in Alaska GDP. The implicit assumption in such assessments is that the increase in the overall economy, as measured by GDP, routinely “trickles down” to Alaska households.

In the column, we explained that much of the “growth” many perceive in Alaska GDP over the last 24 years (i.e., since 2000) is due to inflation, rather than growth in real terms. We also explained that the change in real median Alaska household income over the period has not mirrored the change in Alaska GDP. Instead, we explained that while real Alaska GDP has grown somewhat over the past 24 years, real median Alaska household income has largely flatlined.

In short, there has been no general “trickle down” from real growth in Alaska GDP to Alaska households.

In this week’s column, we discuss why that link generally does not exist to the extent some think and, using available Census Bureau data, examine the growth rates in real Alaska household income by income bracket. We dive into the latter because Census Bureau data reveal significant differences in growth rates across income brackets. Focusing solely on the median Alaska household income doesn’t tell a complete story of the economic conditions many Alaska households face.

The reason that the median Alaska household income does not generally follow Alaska GDP is straightforward. Unlike some other states, Alaska GDP is heavily concentrated in capital-intensive industries, such as oil and mining. In those industries, growth is mainly the result of additional capital investment rather than labor, and, as a consequence, much of the return goes to the sources of the capital, many of which are non-resident, including both the companies’ shareholders and the lenders making the investments.

That trend has accelerated in recent years due to reductions in the labor force in those industries. And even where the labor force, i.e., households, realizes some of the growth, the state’s significant non-resident share of the workforce further reduces the share that ends up in Alaska household income.

In other states with significant oil and mining industries, a share of the growth in GDP typically gravitates to local households through royalty payments made to local owners. Historically, Alaska households have realized similar benefits through the distribution of a portion of Alaska’s commonly owned royalty income as Permanent Fund Dividends (PFDs).

Due to significant cuts in the PFD over the last decade, however, an increasing share of that source of growth has been diverted to state government, which then distributes the income according to its own priorities. Following its path after being so diverted, not all ends up in Alaska household income. And even of the portion that does, a significant share ends up going to households other than those to which it would go if distributed as PFDs.

A good example of the latter is household income derived from the state’s share of Medicaid payments. Many assume that income ends up in the households of those who qualify for the program. But it doesn’t. Instead, the income ends up in the households of the doctors and other health care providers who actually receive the payments.

That example also helps explain another reason median income may not rise even if households share in some of the increase in GDP. That is because such increases may be directed disproportionately to households with incomes above the median, such as the doctors who receive the Medicaid payments. The incomes of higher-income households may rise further, but the median household income, which reflects the middle household with the same number of households above and below, may not.

As the following charts explain, that has been the case with Alaska.

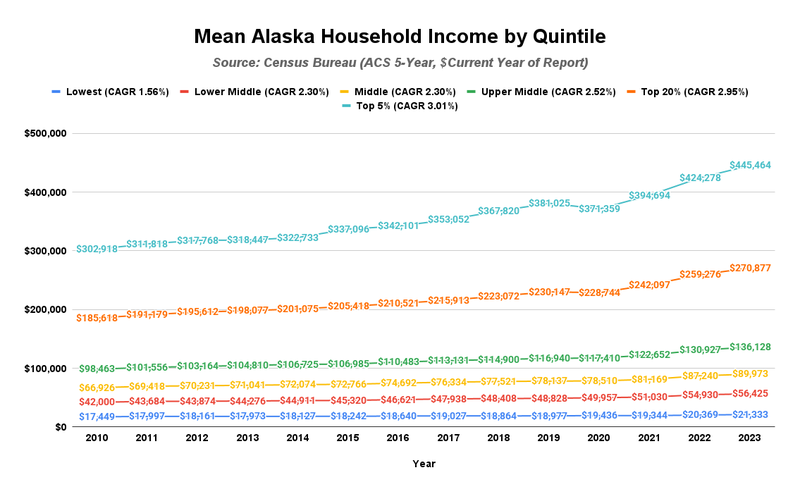

Using data available from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year detailed estimates, which are available from 2010 through 2023, here is the nominal mean household income by year and income bracket for Alaska.

Even from the nominal numbers, it is clear that incomes above the median level, which closely match those of the “middle” quintile, are rising faster than those below it. As reflected in the legend, the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) over the period for the average household in the Top 20% is 2.95%, while the same number for the average household in the Lowest 20% is only 1.56%. Splitting the middle-income bracket evenly between the two, the average CAGR for those in the upper half is 2.65%, while the same number for those in the lower half is 2.00%.

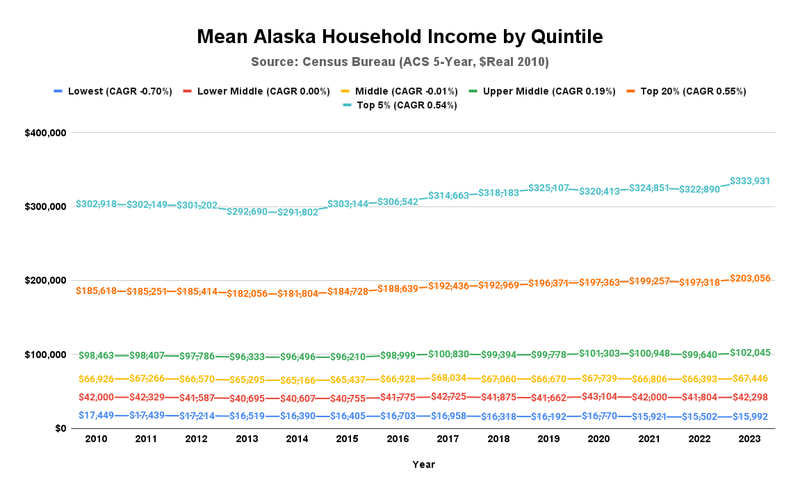

The differences are even more pronounced when the numbers are calculated on a “real,” i.e., after-inflation, basis. In this chart, we have adjusted the nominal numbers reflected in the preceding chart for inflation, as measured over the period by the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in Urban Alaska (Alaska CPI). The numbers are calculated in real 2010 dollars.

As the chart shows, while real (after-inflation) incomes for those in the upper income brackets have risen over the period, those in the lower income brackets have either stagnated or declined.

As reflected in the legend, the compound annual real growth rate (CAGR) for the average household in the Top 20% is 0.55% per year, while the same figure for the average household in the Lowest 20% is negative 0.70%. Splitting the middle-income bracket evenly between the two, the average real CAGR for those in the upper half is positive 0.29%, while the same number for those in the lower half is negative 0.28%.

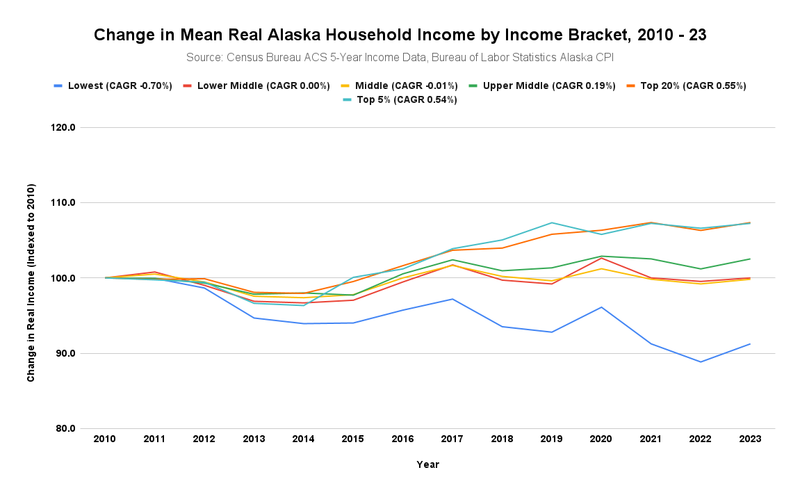

The following chart plots the changes on an index basis to bring the differences into even sharper focus. As the chart shows, while the real incomes for those in the upper income brackets have risen over the period, with ending numbers above 100, those in the middle and lower income brackets have ended the period either where they started (lower middle) or below 100 (middle and lowest).

Some will claim that those are simply the results of Adam Smith’s “invisible hand,” i.e., the regular operation of a free market economy, but the fact is that, over the latter half of the period (2017-23), at least in some respects, they are result of state government putting its thumb on the scale heavily in favor of upper-income households.

By using PFD cuts (the “most regressive tax ever proposed”) to help fund government over the period, rather than other, more neutral and broad-based revenue mechanisms, the state has disproportionately reduced the income of middle and lower-income Alaska households, at least in some instances, as with the Medicaid payments discussed above, by diverting the benefit instead to upper-income households. The results are similar in effect to Texas or Oklahoma levying a targeted tax just on the royalty income received by the state’s various mineral interest owners, many of whom are rural farm and ranch owners, and redirecting the benefits instead to upper-income doctors and other medical professionals.

The impact has not been minor. Over the period from 2017 to 2023, distributing the full PFD and raising government revenues by other, broad-based and neutral means, would have raised the average household incomes of those in the lowest income bracket by approximately 20% on average, of those in the lower middle 20% by approximately 7.5% on average, and of those in the middle income bracket by approximately 5% on average.

Instead of the index curves shown in the chart above, the results would have been more like this:

We have calculated the above chart by adjusting the nominal incomes reported by the Census Bureau for the years 2017 – 2024 by adding back the average annual PFD cuts made by the Legislature, by household, and restating the result in 2010 dollars. While the results may not be entirely precise, given that not all Alaska households receive the PFD and the average household size that does may vary somewhat by income bracket, the results are directionally correct. As the chart indicates, it is highly likely that, had a full, statutory PFD been distributed over the period, all Alaskan households would have realized at least some real income growth.

At least in significant part, that is because, in doing so, Alaska household incomes would have been tied more directly to changes in Alaska GDP. There would have been at least some “trickle down.”

As we explained in last week’s column, there has been a significant divergence over the past quarter-century between how “Alaska” is doing economically and how “Alaskans” are doing. By using deep PFD cuts to fund state government, the Legislature has made that divergence even worse. Even as the overall Alaska economy, as measured by GDP, has grown somewhat, many Alaska households have seen their economic circumstances deteriorate in significant part due to PFD cuts.

Rather than preserving at least some link between Alaska’s GDP and Alaska household income, the Legislature has pushed the two further apart, to the detriment of middle and lower-income Alaska households. Acting consistently with their own self-interest, but not that of many of their constituents, legislators have knowingly sacrificed the well-being of households in the middle and lower income brackets to ensure that those in the upper income brackets remain insulated – and in some instances, indeed benefit – from the impact of growing deficits.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

So you’re talking about people who are living in an area that has no jobs or little prospects and require free money to make it? So move. I had to move from my homeland, where my ancestors lived for millennia, to be able to make it. So can anyone else. What a crock. The dividend was never meant for a reliable source of income. Good grief. What a bunch of crap.

Neither was growing government in government dependent Jobs as public employees, healthcare, education who are worse than any Alaskan taking public assistance

What stupid idea was it to lessen private practices to shove doctors and nurses into corporate health care centers abs hospitals, what we need is more private practices to compete with one another other in quality care and cost

“…….What stupid idea was it to lessen private practices to shove doctors and nurses into corporate health care centers abs hospitals………”

Socialized medicine is as deadly as socialist/communist economic adventures.

Nope.

Wrong.

Bzzt!

Socialized medicine is more deadly than socialist/communist economic adventures?

Bingo!

“……… the state has disproportionately reduced the income of middle and lower-income Alaska households, at least in some instances, as with the Medicaid payments discussed above, by diverting the benefit instead to upper-income households……….”

Here’s a new low. We’ve come to expect such from communist/socialists over the past century. Somehow, medical procedures financed by society for the poor has become an intentional diversion of public assets to rich people (the medical industry). I don’t think I’ve ever heard this one before, even during pressure to reduce overall government spending, but it sure fits the class envy model.

Glad we could help educate you on the state’s actual money flows. Oh, and by the way, in Alaska, the state’s share of the medical procedures delivered through Medicaid isn’t “financed by society.” By using PFD cuts as the marginal revenue source, we are actually paying for them by pushing even more Alaskans into poverty, thereby increasing demand (and the income diversion) further. It’s a significant part of the ongoing “death spiral” the state is creating through its funding choices.

“…….. Oh, and by the way, in Alaska, the state’s share of the medical procedures delivered through Medicaid isn’t “financed by society.”………” More revelation of the truth from the source. Yes, it’s been clear for months from your propaganda campaign that you fully believe the Alaska Permanent Fund, its earnings, and all other state revenue is yours, not the public’s. Medicaid is funded by both federal and state appropriations, and both the federal and state governments are made up of, represent, and act for “society”, defined as “a large group of people who live together in an organized way, share a… Read more »

I defy anyone to find a point in Reggie’s posts.

He knows he’s angry.

And he wants us to know he’s angry.

Understood.

But he simply cannot express a comprehensible point.

“………I defy anyone to find a point in Reggie’s posts………”

Here’s one:

Taxing some to simply transfer the cash to others with no requirement or qualification is a communist/socialist experiment.

Oh, you still don’t understand?

Of course you don’t, I know why, too………….

You sound like your closet socialist buddy McCabe now. He doesn’t want to pay his taxes either, but he still feels entitled to demand a huge handout every fall. That doesn’t stop him, either, from fear-mongering whenever possible about socialist/communist boogeymen.

One of the biggest obstacles to economic sustainability in Alaska is irresponsible politicians who continue to perpetuate the socialistic myth of a free ride here.

“………You sound like your closet socialist buddy McCabe now……….” Ah, it’s the One-Topic-Editor! His therapist shows him a pic of a fish and asks what he sees, and he replies, “McCabe!!”. He gets shown a pic of a pencil, and it’s “McCabe!!” Now he comes and sees a guy opposed to socialist experiments, and he sees………..”Socialist McCabe!!”. “……..One of the biggest obstacles to economic sustainability in Alaska is irresponsible politicians who continue to perpetuate the socialistic myth of a free ride here………” Need I go copy your initial assault on me regarding Chickaloon Tribal Police when you decried the universal… Read more »

Nice non-denial. It’s amazing McCabe can’t find a smarter person than you to shill for him.

“………It’s amazing McCabe can’t find a smarter person than you to shill for him……..”

It’s not amazing at all that you can’t find a moron smarter than you to attack him.

WTF does this mean?

Reggie, would you please stop unposting positively negative anti-posts without first deleting pro-namecalling calls for non-civility?

Yeah, a google search on “Svatass” is next…………..

I’m only uncivil to assholes, Dan. That’s being positively productive towards negative, anti-personalities.

Wow! I just spent a bit reading the pages and pages and pages of hits I got after googling “Mark Kelsey”, “JJAlaska”, “jjalaska”, “JjAlaska”, “Mark Kelsey””Kevin McCabe”, et al.

You’re a pretty sick guy, Editor. McCabe is your life. What would you do if he retired from public life?

You really ought to find a therapist to talk to. You need some serious help. You’ve wasted a lot of years on that guy. Don’t you have something to do?

If the legislature had a “proficiency watch” like the aviation industry does, McCabe would’ve been forced to retire from that, too.

Thanks for being a fan, anonymous coward.

“………Thanks for being a fan, anonymous coward………”

Yeah, I love looking into psycho cases like you. I’m guessing McCabe had something to do with your move from editor/publisher to social reporter, and you’re on a revenge adventure.

Keep it up, Editor. I’ll enjoy from a safe distance……………

So say that! Of course, that’s just an argument against all taxation. As a old Alaskan, I am sure you are too pure to accept any free government programs financed by taxes. Surely you refuse: the PFD; the right to drive a vehicle on a road built by tax dollars; any treatments from doctors educated in publicly-underwritten universities; monthly Senior Benefits cash; senior, disabled, residential, or business propety tax exemptions; police protection supported by tax dollars; meals cooked in restaurants inspected by government agents; free senior car registration; airline flights monitored by federal air traffic controllers; and half-price senior public… Read more »

“…….. that’s just an argument against all taxation……..” No, it’s a refusal to pay taxes in order for that money to simply be mailed to others in the form of cash. I’ll pay for services, thanks. “……..half-price senior public transit tickets………” The last bus I rode was in the 1960’s while on leave in the Army. Now airports remind me of Greyhound bus stations. “…….police protection supported by tax dollars………” Police protection is precisely what I want, and I’m talking sworn LEOs with guns and body cams. I love APD, and enjoy the Leftist meltdowns each time APD officers shoot thugs… Read more »

“……..As a old Alaskan, I am sure you are too pure to accept any free government programs financed by taxes……….”

Here’s a question for you, Dan:

How about refusing all federal funding, stop state funding of all programs, and just divvy up the annual budget in cash to all Alaskans, and that’s it? We’re all on our own. No road maintenance and repair. No university. No police. If you want to spend yours on Jack Daniels, go for it. Want to spend it on a $100,000 electric motorcycle, do it. Good idea? No?

Tell us.

Not responsive to anything I wrote.

The moment I challenge Reggie’s hypocrisy on the socialism he likes receiving, he goes whataboutism and changes the subject.

Reggie’s impossible to converse with.

“……..Not responsive to anything I wrote………”

You aren’t Swiss.

“………The moment I challenge Reggie’s hypocrisy on the socialism he likes receiving, he goes whataboutism and changes the subject………”

That’s exactly what you did with your “what about” all kinds of silly shit that I don’t use or don’t exist, like senior bus rides and free senior car registration, or whatever after I oppose a Universal Basic Income scheme, that I’ll have to pay for with an income tax, so you can get a check to spend at the casinos down there at your winter home in Vegas. Do you register your car free in Nevada, Dan?

“………It’s a significant part of the ongoing “death spiral” the state is creating through its funding choices………,.”

Funding the Permanent Fund Dividend is a “funding choice”, too, and is actually the largest single appropriation line item in the annual budget, as well. Before there was a PFD, Alaska’s state income tax was repealed, and that was the obvious proper order. Imagine trying to give money away while taxing people’s income…………yet that’s precisely what you’re advocating now, after so many have taken the free money for granted.

🍿🍿🍿

It has as much to do with Dumleavy’s veto power as it does with the Legislature.

“A good example of the latter is household income derived from the state’s share of Medicaid payments. Many assume that income ends up in the households of those who qualify for the program. But it doesn’t. Instead, the income ends up in the households of the doctors and other health care providers who actually receive the payments.” This statement, while true, is misleading. If not for the program, the beneficiaries would have to pay out of pocket for their health care. So the program, in a way, lifts the income of beneficiaries on an after-health-cost basis – it keeps their pockets from… Read more »

This author keeps advocating taxing income to pay dividends. His main argument assumes that cutting pfds is just a tax like any other tax. But cutting dividends is not just like any other tax – people get dividends for doing nothing more than living in Alaska for another year (or for some >180 days) while people get earned income from working. It is not fair to tax hard-earned income just to pay dividends to people who do nothing but live another year in Alaska. To be clear, I believe that SB21 was passed with significant funding from the support alliance and the oil… Read more »

Thanks for pointing out we are ALL losers for living ON Alaska

If it wasn’t for government money then all who’d be left would be the Alaskans roughing it out on homestead lands

This is the Arctic and sub-Arctic. It’s a hard land. It’s like this around the planet at these latitudes. Only an estimated 80,000 natives lived here when the Russians arrived, and there were fewer than 65,000 Alaska natives in Alaska and elsewhere upon passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1972. The total population of Alaska was less than half what it is today when pipeline construction began. Why do we have to pay people to stay here, especially if we have to pay income taxes to do it?

Good post and thought provoking. I would encourage you to research the impact of approximately 50% of our Medicaid spend comes from 100% FMAP and is paid out at the all-inclusive rate (AIR) to tribal health organizations. The AIR is published every year for Alaska in the Federal Register and is a cost based rate for all outpatient and inpatient services based off the annual cost reports of five tribal health organizations. This is very significant because ultimately it is in the State’s best interest to reduce state general fund expenses by maximizing the 100% FMAP for tribal members who… Read more »

“…….. it is in the State’s best interest to reduce state general fund expenses by maximizing the 100% FMAP for tribal members who are on Medicaid………”

Asking because I don’t know:

Alaska Natives qualify for Public Health. Does Medicaid pay those costs? If not, why would natives qualify for both Public Health and Medicaid?

Tribal members can have Private insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare coverage. The state can receive 100% reimbursement (FMAP) from the federal government for tribal members enrolled in Medicaid.

Contracted and compacted tribes receive fixed amounts of funds from the federal government to partially cover former federal government expenses when tribes exercise their rights under PL 93-638.

Public Health is not involved in any of this.

Wowee, Reggie’s spamming the page again. It’s like watching someone masturbate.

“………It’s like watching someone masturbate………..”

Do you enjoy that often?