In our column a couple of weeks ago we looked at how much oil production would need to increase to balance the budget over the next decade. As we concluded there, it’s a lot. So much, in fact, that it’s unrealistic to think it will occur.

That led some to ask us, in the alternative, to look at how much the level of “government take” from oil would need to increase to accomplish the same objective. The level of government take is the percent of oil revenues (usually expressed as $/bbl) received by the producer, in turn paid to the state as royalty and taxes.

Before we start down this road let us suggest that, just like an “oil production increase only,” an “oil tax only” approach to fiscal policy also seems unrealistic. Just two years ago Alaska voters overwhelmingly rejected Ballot Measure 1 – a proposal to increase oil taxes on certain producers and fields on the North Slope by what the proponents estimated to be about $1 billion – by a margin of roughly 16% (58% to 42%).

Heck, the past two sessions the Legislature hasn’t come close even to addressing what some refer to as the Hilcorp loophole, an obvious and easily fixable glitch through which the Department of Revenue (DOR) recently estimated Hilcorp avoids paying on average roughly $90 million/year in corporate taxes that previously were paid by its predecessor.

Leaving that glitch untouched alone costs Alaskans nearly $150/Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD). If the Legislature isn’t up to fixing that, why on earth would anyone think its interested in raising even more through taking on production or other oil related taxes.

But the question is an interesting one and, as we discuss a bit later in this column, one that may prove helpful going forward as part of an overall fiscal solution.

As we did in analyzing how much additional production would be required to close the deficit, we need to start by defining what the size of the deficit is.

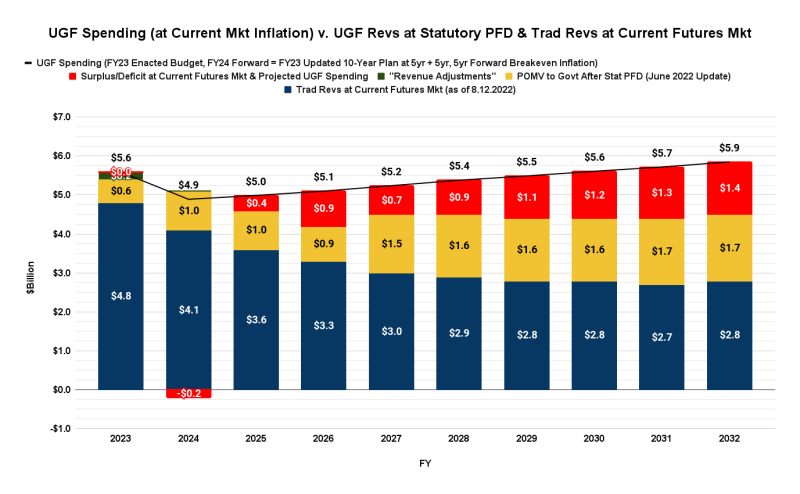

At the production levels projected in DOR’s Spring 2022 Revenue Forecast – and using the most recent oil futures prices – here is what the outlook for the “current law” (statutory Permanent Fund Dividend) budget looks like over the same span, using our most recent “Goldilocks charts”:

At currently projected revenue and spending levels, deficits (red, at the top of the bars) begin in FY 2025 and build throughout the remainder of the current decade and beyond.

So, what additional levels of government take from oil would be required to close those deficits.

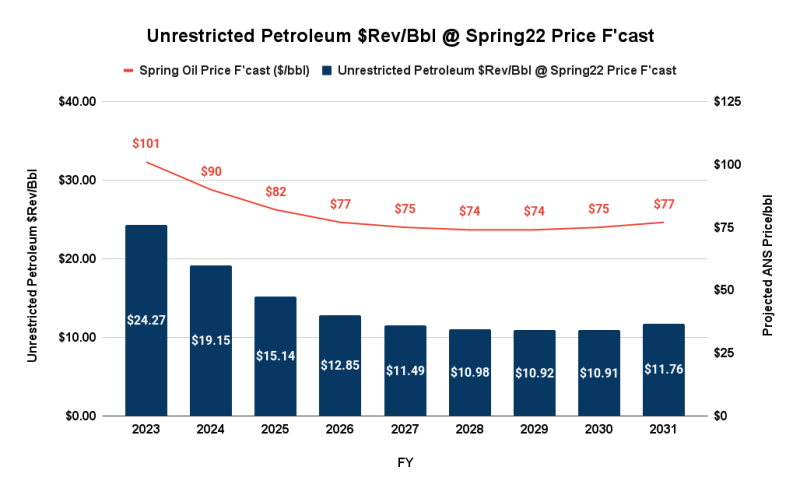

There are several ways to look at the issue. Let’s start with a basic one. According to the most recent Spring Revenue Forecast, under its existing fiscal structure the state is projected to receive the following in unrestricted funds (per barrel) over the next decade from Alaska North Slope (ANS) oil.

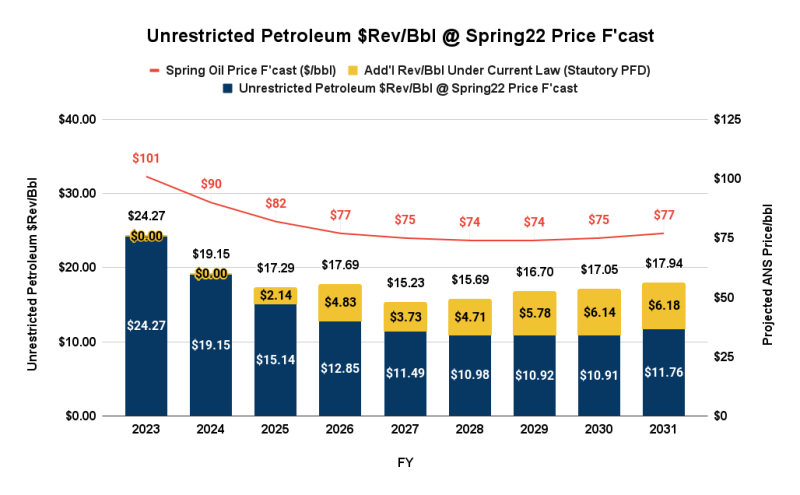

Absent other revenue contributions, here’s the additional amount (in gold) the state would need to receive per barrel to close the projected current law (statutory PFD) deficits:

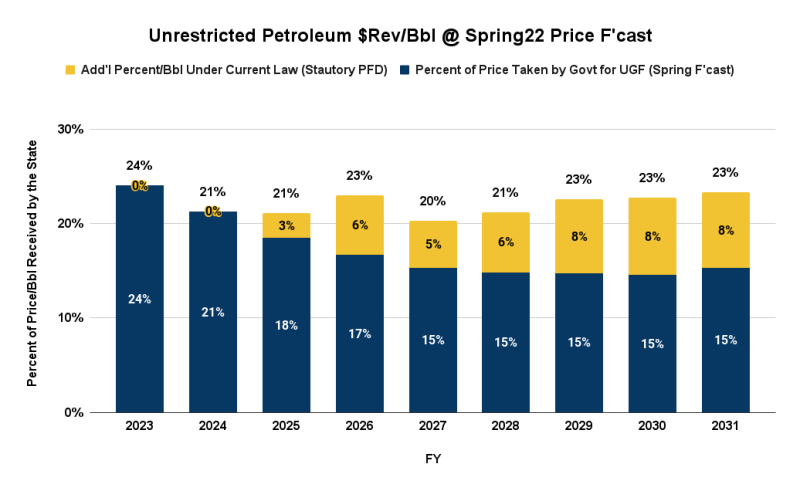

Another way to look at the impact is to focus on the required percentage increase over the currently projected government take levels. Here is the government take level, per barrel, currently projected in the Spring Forecast (blue) and the additional amount which would be required to balance the budget, absent other revenue contributions, under current law (statutory PFD, gold):

Certainly, many will immediately protest that the oil industry couldn’t possibly afford making any additional contributions; it’s interesting to note, however, that even with the additions, the percentage take levels in any given year don’t even reach, much less exceed, that already projected for the current fiscal year (FY23).

But it’s hard to dispute the argument that increasing the take level likely would have some impact on investment levels, and through that, future production.

That should not end the discussion, however.

For example, if, to pick a number, the effect of raising the average take level over the next decade from the currently projected 17% to 22% was a corresponding reduction in production of 5% from currently projected levels, that would still be a very good deal for state revenues.

Yes, the state would lose the revenues from roughly 25 thousand barrels a day of production, but the increased revenue it made on the remaining 500 thousand barrels would still produce a significant net gain. And that gain certainly would reduce the amount of revenue the state needs to take from other sources (e.g., PFD cuts) to close its deficits.

On the other hand, if the effect on investment of raising the average take by that amount was a reduction in production of 50% from currently projected levels, pursuing that course would be a bad deal for state revenues. The increased revenues on the remaining 250-ish thousand barrels wouldn’t be enough to make up for the reduction in revenues from the production which is lost.

Between the two examples is a “revenue maximizing” point – what those who work in the area refer to as a “sweet spot.” But finding it requires a lot of information, making some assumptions about decline curves and some dedicated work. To be honest, over the past ten years we’ve not been aware of any governors, group of legislators – or for that matter, voters – who have demonstrated the interest and patience required to pursue calculating it and, more importantly, applying it in practice.

As we mentioned above, however, while we believe relying solely on the approach of raising the level of government take to balance the budget is unrealistic, pursuing the issue nonetheless may prove helpful going forward as part of an overall fiscal solution.

Occasionally, some talk of pursuing an “all of the above” fiscal solution that would be composed, in part, of a revenue package of some PFD restructuring (e.g., to Percent of Market Value 50/50), some increase in oil taxes and some individual taxes.

Generally speaking, talk of any increase in oil taxes, even as part of an “all of the above” solution, usually is met by howls of protest from the state’s oil sector, including Top 20% led Keep Alaska Competitive, which seems to personify the old Sen. Russell Long adage of “don’t tax you, don’t tax me, tax those guys behind the tree.” (The Alaska version is “don’t tax oil, don’t tax the Top 20%, tax the other 80% of Alaska families behind the tree using PFD cuts.”)

But even the current administration’s Department of Revenue includes some increase in oil taxes as part of the fiscal options it has put on the table.

In its most recent “Fiscal Plan Model,” DOR includes two oil tax-related options for consideration. The first is, essentially, fixing the Hilcorp Loophole, which raises, on average, roughly $90 million per year over the next decade. The second is “Reduce Current $8.00 Per Barrel Tax Credit by $3.00”. That raises, on average, roughly $400 million per year over the next decade. (Interestingly, the DOR projection does not appear to ascribe any loss in investment or production to those increases.)

Combined, that is the equivalent of raising government take levels over the next decade, on average, from roughly 17% to 20%. Not a full solution, which would require raising government take levels by an average of 5 percentage points, but a material contribution.

In order to achieve even that material contribution, however, Alaskans, and more specifically, legislators, need to be willing to engage in at least some discussion about modifying oil taxes, and that requires some numbers, as well as some factual – not arm-waiving – discussion about what the marginal impact of those numbers may be on investment, and thus, production levels. The open question is whether legislators, special interest groups and everyday Alaskans are willing to engage in that discussion.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Ballot Measure 1 wasn’t overwhelmingly rejected, it narrowly failed 47% to 52%. Mostly voted against by people who bought into the propaganda that the Alaska economy would fall apart and everyone would lose their jobs if the oil companies had to pay a fair share for the State owned oil. Then, ironically, BP laid off nearly 300 people almost immediately after the ballot measure failed. And you can bet all of those people and everyone they knew voted against Ballot Measure 1. Not to mention thousands of others that feared that they may lose their livelihood if Ballot Measure 1… Read more »

Ballot Measure No. 1 – 19OGTX

Precincts Reported: 441 of 441 (100.00%)

Yes: 145,392 (42.14%)

No: 199,667 (57.86%)

https://ballotpedia.org/Alaska_Ballot_Measure_1,_North_Slope_Oil_Production_Tax_Increase_Initiative_(2020)