Earlier this week, while working through some data on states that use a flat-rate income tax to raise revenue (14 now, with two more in process), something dawned on us that hadn’t before.

It’s pretty startling. Under Alaska’s marginal revenue approach – which is based on withholding and diverting to government a large portion of the funds from the state’s commonly owned wealth statutorily designated for distribution to Alaska families as Permanent Fund Dividends (PFD) – Alaska takes more as a share of income from middle and lower-income Alaska families than California, New York, or any other state takes from its millionaires and billionaires.

Let that sink in for a moment. Using the data we compiled for a recent column (based on the latest state-level data available from the Internal Revenue Service), as a share of income, Alaska takes more on average from the lower 75% of Alaska households, which, combined, have an average adjusted gross income of $48,384, than California, New York, or any other state takes from of its residents with adjusted gross incomes 20 times ($1,000,000) and more higher.

We have long realized that, as University of Alaska-Anchorage Institute of Social and Economic Research (SER) Professor Matthew Berman most recently reminded us a couple of years ago, “a cut in the PFD is … the most regressive tax ever proposed.” What we hadn’t focused on before is that it is even more regressive than any other state’s income tax is progressive.

Put another way, in the same way that California and New York are the pacesetters of state progressive tax rates, Alaska – and the Alaska legislators who vote for them – are the “king” of regressive tax rates. Indeed, from at least one perspective, Alaska’s rates are more regressive than even California and New York are progressive combined. Separately, California and New York have marginal state income tax rates of 13.3% and 10.9%, respectively. Combined, that’s 24.2%.

Compared to that, applying this year’s PFD cut, Alaska has a marginal tax rate of over 37% on the lowest 25% income bracket, fully half again higher than California and New York’s combined rate. You could even add Hawaii’s 11% marginal rate to California’s and New York’s, and the combination would still be less than the average rate on Alaska’s lowest 25% income bracket.

And California and New York’s combined rate is still less even than the average rate on Alaska families in the lowest 50% income brackets (the lowest 25% plus the lower middle income bracket).

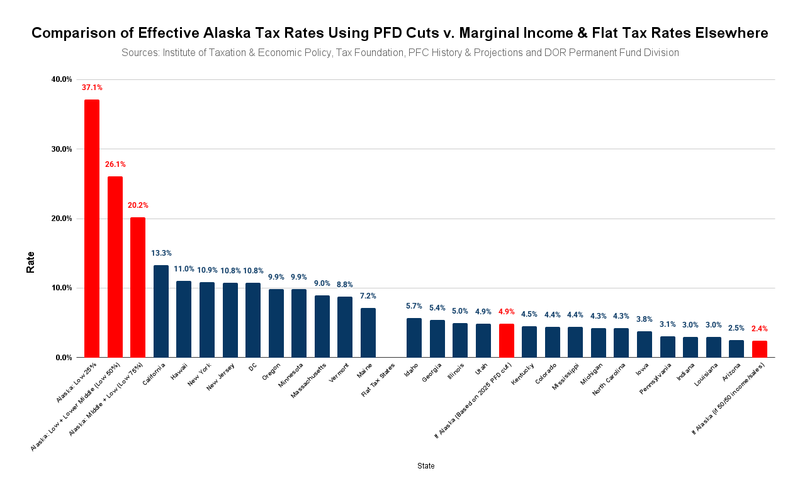

Here are comparisons between Alaska and various other states, including all current flat-tax states.

On the left side of the chart, we compare the average rate of government take on Alaskans using PFD cuts by various income brackets (in red) to the nation’s top 10 marginal state income tax rates.

To show how hugely regressive the impact of using PFD cuts is, we calculate the average impact separately on those in Alaska’s Lowest 25% income bracket, on those in the Lowest 50% income brackets (by combining the impact on the Low 25% with the Lower Middle 25%), and on those in the Lowest 75% income brackets (by combining the second group also with the Upper Middle 25%). The average impact expressed as a share of income on every grouping is larger than the marginal (highest) rate in every one of the nation’s top 10 state income tax states.

In short, Alaska is taking, on average, a larger share of income from its middle- and lower-income families than any other state is taking from its millionaires and billionaires

To us – and to others we have talked to nationally about it – that’s shocking. As distortionary as anyone thinks California and New York’s revenue policies are, Alaska’s are worse. For those who think that California and New York’s marginal rates drive the outmigration of some of their top earners to Texas and Florida, Alaska’s regressive rates similarly do much to help explain the net outmigration of Alaska’s working-age, working-class families to the lower 48.

They also help explain Alaska’s poverty levels, which, in turn, help drive Alaska’s high levels of government support targeted at that sector. As Professor Berman explained in his earlier column, which he subsequently backed up in a recent research paper, relying on PFD cuts to raise revenue “push[es] thousands of Alaska families below the poverty line.”

For comparison, on the right side of the chart, we compare the flat tax rates of the states that currently use the approach to the rates that might apply if Alaska covered the costs of its current deficits in the same way.

The first Alaska rate (in red, at 4.9%) is the rate that would apply if Alaska used a broad-based flat tax to generate the same amount of revenue ($1.77 billion) as was diverted from Alaska families to government through PFD cuts in this year’s budget. As in a previous column, we have assumed that 10% of the cost would be recovered from non-residents. The rate would be even lower (4.6%) if the tax were structured to raise 15% of the revenues from non-residents.

The second Alaska rate (in red, at 2.4%) is the rate that would apply if, as many other states do, Alaska used both a broad-based flat tax and a similarly broad-based sales tax to cover this year’s deficit. Other states mix the two in various proportions. For simplicity, in this presentation, we have assumed that each is used to raise 50% of the overall revenue requirement.

As we explained in a previous column, those rates could be even lower if, as part of a comprehensive fiscal package, Alaska also restructured its oil tax rates to meet the “maximum benefit” mandate of Article 8, Section 2 of the Alaska Constitution, and even lower still if, as we have discussed in other previous columns, the Permanent Fund Corporation’s investment policies were reoriented to more closely align with the “Buffett 90/10” approach.

But even without those additional steps, eliminating Alaska’s ultra-regressive, California & New York-like extremist revenue approach by, instead, offsetting Alaska’s deficits through a flat tax would significantly improve the lives of Alaska’s middle and lower-income (80% of) families, as well as increase Alaska’s competitiveness for retaining and attracting working-age, working-class families.

Even if the taxes were structured so that only 10% of the revenues were raised from non-residents and all of the deficit was covered through a flat tax, Alaska’s flat tax rate would still be lower than four of the other states using a similar approach, including bustling regional cohorts Idaho and Utah. If the revenues were structured so that only a portion was raised through a flat tax – with the remainder raised through sales taxes, revised oil taxes, improved Permanent Fund returns, or a combination of all of the above – Alaska’s resulting flat tax rate would be among the lowest, if not the lowest, in the nation.

By replacing the current revenue structure that takes money only from Alaska families and is hugely regressive, a flat tax also would significantly improve the flow of cash into – and thus, the strength of – Alaska’s economy.

All of that would be a massive improvement over the worst-in-the-nation approach Alaska, through the Alaska Legislature, is currently employing through its use of PFD cuts.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

Yup.

“………Let that sink in for a moment……….”

I prefer to let it sink to the bottom of the socialist mud puddle than into my intellect, thanks.

This is a joke. Alaska does not even have a tax policy to compare with other states. This is all made up garbage. The proposed flat tax here would be immensely regressive and hurt poor people. It’s just stupid. Go have your tax but give poor people a break.

Who is “We”?!?

What part is “made up”?

The part after the word “Earlier”…………..

If I wanted to live in California or New York, I would. We are Alaska and many of us don’t care how other states rape their citizens.

Yeah!

Learning from the experiences of others is gay!

We should pretend that the rest of the nation doesn’t even exist!

Yay ignorance!

You might be big into pretending, Dan, but I don’t even know how to. It’s just too deadly.

That’s not going to fix that the legislature doesn’t know how to live under their means

Alaska revenue will never increase as long as it finds more ways to increase taxes on its recycled money

But go ahead spend spend spend ahead

GenX and Millennials need to leave something they built behind and that might as well be a debt then you can go out of this life knowing you accomplished something

This article is premised on a lie.

The laws of Alaska do not require the state to distribute “commonly owned wealth statutorily designated for distribution to Alaska families as Permanent Fund Dividends (PFD)”, as Mr. Keithley puts it.

Because there is no such wealth that the state must distribute.

The laws of Alaska allow the Legislature, if it so chooses, and subject to executive veto, to appropriate Permanent Fund Income to residents through the Permanent Fund Dividend program.

But there is no requirement that it do so.

Kiethley’s lie was rejected by our Supreme Court long ago.

You misread the situation. Alaska statutes have, for a long time, and still require (“shall transfer … for distribution“) the distribution of a portion of Alaska’s commonly owned wealth in the form of Permanent Fund Dividends. The statutes have neither been repealed nor, despite repeated and considerable efforts to do so, amended in the amount of the distribution they provide. Yes, the Alaska Supreme Court has said that, as part of the annual appropriations process, the Governor or Legislature may, on a year-to-year basis, deviate from the statute by withholding an amount from distribution and diverting the amount withheld to… Read more »

“………Yes, the Alaska Supreme Court has said that, as part of the annual appropriations process, the Governor or Legislature may, on a year-to-year basis, deviate from the statute by withholding an amount from distribution and diverting the amount withheld to other purposes………”

Yes, and that amount withheld can amount to the “full” amount. IOW, the dividend amount can be zero………just like all other appropriations.

“………Yes, the Alaska Supreme Court has said that, as part of the annual appropriations process, the Governor or Legislature may, on a year-to-year basis, deviate from the statute by withholding an amount from distribution and diverting the amount withheld to other purposes. But as Professor Berman has pointed out, when it does so, the Legislature is effectively taxing the amount to be distributed by withholding and diverting a portion to the government………” Lawyeresque bullshit. I quote from the Weilechowski v Alaska decision: “…………The narrow question before us is whether the 1976 amendment to the Alaska Constitution exempted the legislature’s use… Read more »