Saturday night my mind was racing. It had been 14 days since I had entered the Flying Dog Hostel in the Miraflores district in Lima, Peru, trapped with over 20 others from around the world. Flights were starting to happen at this point. My friend Ali from Mexico had left on a flight to his home in Mexico early that morning, paid for by the Mexican government no less. On the night prior, three of my friends from Ireland got word days in advance that they were booked on a flight back to Ireland on Sunday, organized for by their government and costing around 200 euros. A bus would pick them up, as well as other Irish leaving Peru on the flight.

I was in a state of mental ambiguity and the tension I felt was escalating. At that point I still had not heard from the U.S. government about a spot on a repatriation flight back home. On one hand, I was ecstatic for the other people at the hostel. My friends were going home. On the other, I feared with the ongoing lack of efficiency with the repatriation of U.S. citizens abroad, I would eventually be alone, waiting for a ticket in isolation. Congressman Don Young’s chief of staff read my first article. She made contact with me through Jeff Landfield about the situation. She provided me with reassurance that I would not be forgotten.

I sat on a bunk in the room, termed by an old eccentric man named Alphonso (or as we called him, Pappi) “Tu oficina”. Pappi was a 65 year old Peruvian citizen who apparently had no home and lived at the hostels around Miraflores. He spoke almost no English. He was known to rise in the morning, take a strong toke from his “pipa”, and extort, “Estoy muy feliz! I am very happy, happy man.” When I would hang out in that room I would sit at the night table on a small chair. One day, Pappi declared this desk my oficina, and that I was “el presidente del cuarto feliz”, or the president of the happy room. He had on a few occasions explained this concept to us in Spanish by walking out the door, walking back in, asking permission to see el presidente, and shaking my hand as I held back laughing uncontrollably.

As I laid on the bunk in my office I refreshed my email every ten minutes. Anticipation for the email, including details about my ticket, was all encompassing. Emails were coming in from the U.S. Embassy in Lima intermittently, but they were just repetitions of prior mass generated emails with a notification at the end informing me to wait for an email I would receive when placed on a repatriation flight. At this point a repatriation flight was my only option, as the Peruvian president had announced an extended quarantine period going until April 13th. This had once again caused commercial airlines to cancel all tickets that had been made for the end of the initially proposed quarantine period.

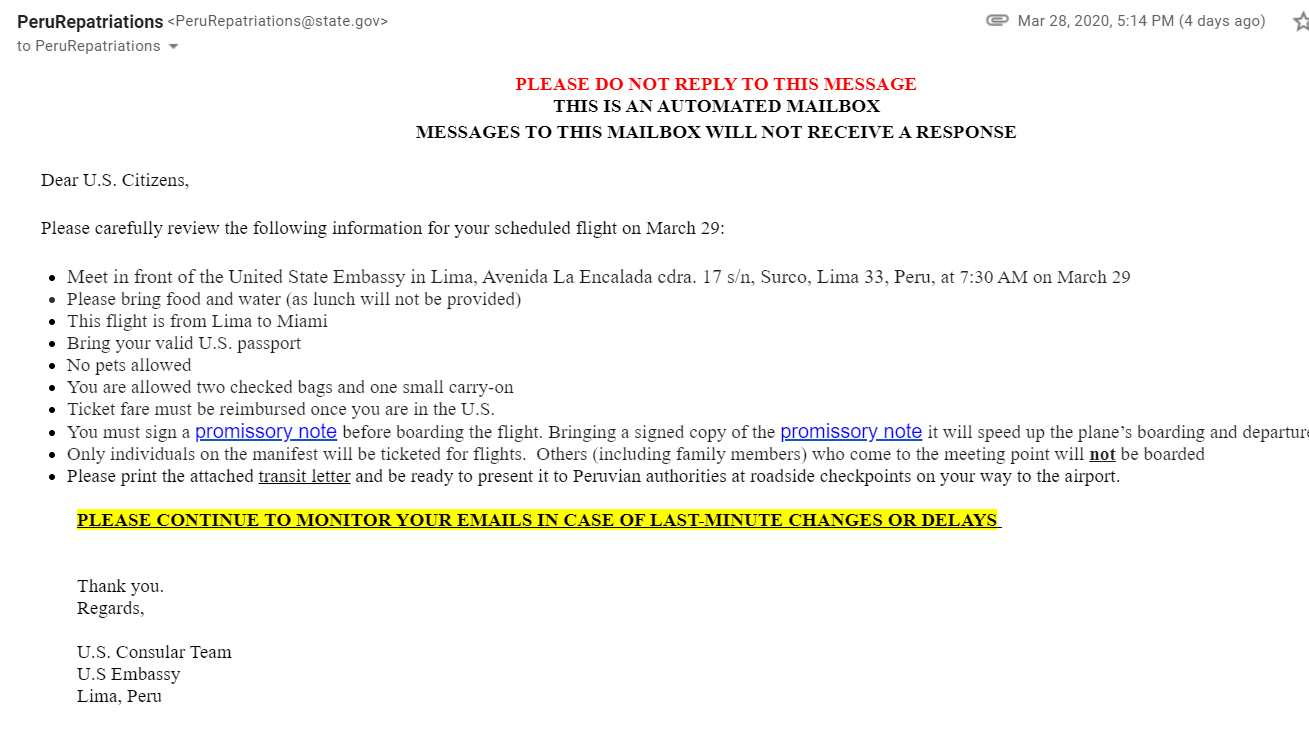

Then it happened. At 5:14 p.m. on Saturday, March 28th, my email refreshed with something new regarding my repatriation flight details. I jumped from the bed, exclaiming, “I got my flight details! I’m going home!” and made my rounds embracing my cohorts. I quickly read the email which instructed me that I was to find transport and meet in front of the U.S. Embassy at 7:30 a.m. the next morning to begin the process of getting onto a flight to Miami. I was to bring my own food and water as none would be provided.

That night I made my rounds at the hostel to say goodbye to the people I entered calling strangers, and would leave knowing as friends. It’s hard to describe the feeling, but although I was happy to be going home, I knew I would miss the company of these people, and that what we had gone through together was a moment in our lives we would never forget.

The next day I was out the door at 6:45 in the morning. I quickly hailed a taxi and took off toward the embassy, going through multiple Peruvian military checkpoints. By the time I got there, the line was massive, wrapping around the block from the front entrance. I paid the cabbie and took my place in line with the others. I noticed at one point a woman show up in a cab and was begging to be let on with her with her children. One of the officials started to talk to her about it.

At 7:30 a.m. an official began to loudly announce to everyone in line the process we were about to go through, and to use the bathrooms then because our options would become more limited throughout the long day ahead. We would have to fill out a promissory note while in line if we hadn’t printed it and filled it out already. This promissory note was to hold each person on the flight accountable for paying the price of the ticket, which I was given no details of prior to signing. After blindly signing the note, I was processed at a few different tents that had been set up, and shuffled into a line of people that had received a confirmation email. I was shocked to see that the standby line for those that had just shown up to try and get on the flight was hundreds of people long. People were desperate and wanted to get back home at any possible chance. I couldn’t blame them.

After being processed I was shuffled onto one of several large tour busses that were pulling up beside the embassy. We were then taken across the city to a Peruvian military air force base. There were around twenty other busses waiting outside the air force base. Once through the guarded entrance the bus made its way to a hangar at the end of the base. A U.S. military member boarded the bus and informed us of the process we were about to go through to get on the plane.

We walked off the bus and made our way inside the hanger, bordered by Peruvian soldiers as if to hold us from making a run for it. Inside the hangar, chairs had been set up in large rows. We were told where to sit and to put our bags we wanted checked in front of us in a line. Airline personnel tagged and recorded our bags, after which Peruvian officials stamped everyone’s passport to exit the country. Dogs were then brought down every line to sniff the bags for bombs and drugs. When this was all done we were loaded back onto the busses and driven out onto the tarmac where massive jumbo jets awaited to be boarded. From there, we were herded off of the bus and into the planes, told to go to the back and fill up every seat possible.

By the time the flight was ready to take off around 2 p.m. it was packed. I could hear the wails of small children everywhere. As the wheels lifted from the ground, everyone on the plane began to cheer and clap. We were all ready to go home. At one point during the flight a flight attendant approached me in my seat to ask me why the flight was so full. I was flabbergasted to find that the airline had not told the crew that it was a repatriation flight for American stuck in Peru.

Once in Miami, I shuffled off the plane and went through customs as quickly as I could. Since I had not been given details of when the flight would arrive in Miami it was too late to book my other flights to get back to Anchorage. With the help of my friend in the travel industry back home I was able to book flights for the next day. I spent the night at a seedy roach motel in Miami for the night.

The next day I began my journey to Anchorage, which would take all day and part of the night. I was shocked to see how empty the airports were in both Miami and Seattle. Few businesses were open in the airports, so I had lunch and dinner at McDonalds. At 2 a.m. on the 31st my flight to Anchorage from Seattle touched the tarmac. When I got off the plane and into the airport I had to stop and wipe tears from my eyes. Our governor had mandated that any travelers coming in from out of state would have to undergo a 14-day self isolation quarantine. So I had to sign some paperwork at the airport with a pencil I was told to drop in a containment box after finishing. I quickly grabbed my bag and got a Lyft ride back to my home.

I am now at my home in Alaska, two days into my 14-day isolation period. I cannot go out into the public for any reason. If I need groceries, I have to organize that with a delivery service or a friend. I cannot go to work. I cannot walk around the block. This is the inevitable last hurdle, and ending to my story. The past month has been the most unusual string of events in the course of my life. I’ve laughed. I’ve cried. I’ve danced and I’ve screamed. I cannot help but use this time to reflect and bring clarity to the growth I have undergone, and shared with others in this time. One day I will go back to Peru. I will walk the streets of Miraflores, busling with the excitement of thousands of people, smelling the sweet and savory aromas of the world renowned restaurants. I will close my eyes and in my mind again will find myself on those empty streets. In chaos comes peace, and when order comes again, I can only hope the birds will still sing as joyously as they did during this time of solitude.

Until next time, I’m Tim and I’m back home.

Tim Weise was born and raised in Alaska. He is an avid world traveler. He spent a year in Australia in 2017 where he met Jeff Landfield. They became friends and had many loose adventures.

Truly happy to read you made it back to Alaska. Welcome back.

You didn’t finish telling us about how the promissory note turned out. How much did the repatriation flight cost?

It turned out to be $980 not including the tickets back to Anchorage from Miami. It took a while for them to mail me a letter about it. I’m still getting 50 a month taken by the Department of State.

We were all ready to go home. At one point during the flight a flight attendant approached me in my seat to ask me why the flight was so full. I was flabbergasted to find that the airline had not told the crew that it was a repatriation flight for American stuck in Peru.

With the help of my friend in the travel industry back home I was able to book flights for the next day. I spent the night at a seedy roach motel in Miami for the night.

https://noithatdongthanh.vn/thi-cong-noi-that-khach-san.html