After already having set a dollar target for the “New Revenue Measures” required to balance the state’s budget over the next ten years in the Dunleavy administration’s Fiscal Year (FY) 2027 Budget Overview and 10-Year Plan (10-Year Plan) published in December, and teasing in a press availability on Wednesday that he would discuss at least one significant segment – a “seasonal sales tax” – in his State of the State speech last night, Governor Mike Dunleavy (R – Alaska) both surprised and disappointed by failing to provide any details of his proposed fiscal plan in his speech.

With this year’s legislative session already underway and other issues moving to take up valuable legislative attention, last night’s speech was a prime opportunity for the Governor to seize the initiative and set the tone for dealing with what the administration’s own 10-Year Plan admits is “the stressed fiscal situation Alaska is in.”

Yet, despite promising in the 10-Year Plan in December to propose a long-term, sustainable fiscal plan “leading up to the next legislative session,” in last night’s State of the State, the Governor now says that he plans to introduce a fiscal package next week, during the second week of the session.

Once introduced, we anticipate delving deeper into the various components of the plan in future columns. Because of the issue’s overriding importance, however, we are also using this week’s column to provide an initial overview of our reactions to what, at least, has been described on the pages of the Alaska Landmine as likely to be included in the Governor’s fiscal plan. As reported by the Landmine, the provisions include the following:

- Raising the minimum oil production tax floor from 4% to 6%. The minimum tax typically kicks in under a combination of high investment and/or low oil prices. They estimate the increase to bring in an additional $130 million. This would start in 2027 and would return to 4% in 2032.

- A 15 cent per barrel fee for Alyeska Pipeline to support maintenance on the haul road and along the pipeline. This would be passed on to the oil companies. This would start in 2027 and would not end. Estimated revenue is $25 million.

- A reduction in the corporate income tax from 9.4% to 2% over seven years. The estimated revenue decrease between 2031-2035 is $135 million, and then $514 million between 2036-2042.

- A statewide sales tax that would move between 2% and 4%. The tax would be set at 2% between October through March and 4% between April through September. This would go down to 0% in 2032. They estimate the revenue at $765 million per year.

- A constitutional amendment to combine the Permanent Fund corpus and Earnings Reserve Account into one account, a maximum 5% yearly draw, and a 50/50 PFD based on the annual draw. The 50/50 PFD would start in 2028 and would be estimated at $3,600 per person per year.

- Limit growth on spending to 1% through a statutory spending cap.

- Establish a sunset and reauthorization process.

Despite our disappointment that it was not presented last night, our first reaction is that, if he subsequently offers something along these lines, the Governor deserves credit for finally delivering a fairly substantive fiscal plan. We had been concerned that he would let his final year in office pass, as he has done in the past, effectively kicking a solution to what the administration itself admits is the state’s “stressed fiscal situation,” even further down the road. While, as we will discuss further in a moment, we have some significant issues with what the Governor reportedly is preparing to propose, that does not take away from the fact that, unlike in previous years, and assuming he follows through, he is finally offering a plan that relies on realistic sources of revenue.

Our second reaction is that, again, assuming the finished details reflect what the plan is reported to contain, he is starting the conversation in the right areas. As we have explained in previous columns, the state should be taking in more in terms of oil revenues, restructuring the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) should be part of a comprehensive solution, and the state should be using a broad-based tax to both raise a portion of its revenue requirement from non-residents and significantly reduce the impact of its current revenue approach on middle and lower-income (80% of) Alaska families.

Assuming he follows through and opens the door to discussions on those issues, we hope the Legislature will quickly seize that opening to begin developing and finalizing a comprehensive plan.

That said, we have some issues with the Governor’s likely proposals, as reported.

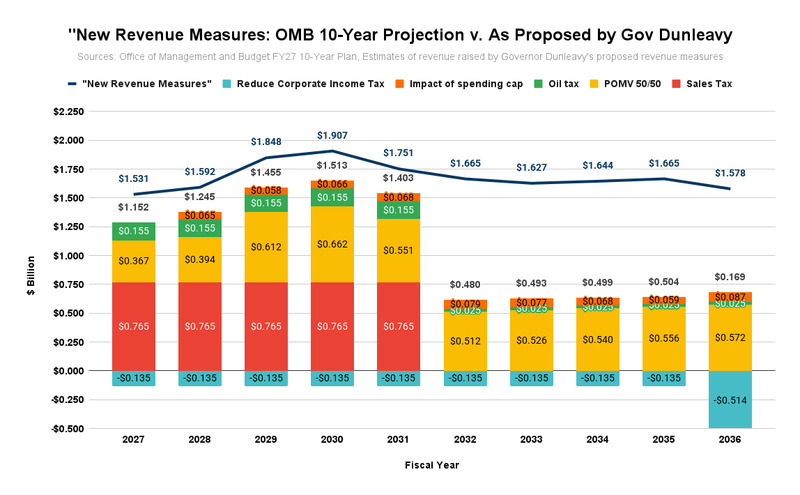

The first is that they don’t appear to fully address the scope of the problem that the administration itself defined in its 10-Year Plan. In the following chart, we compare the level of “New Revenue Measures” projected in the 10-Year Plan (the blue line) with the revenue levels projected from the measures described in the reporting on the Governor’s plan (the columns). As is clear, even accounting for the impact of the Governor’s proposed spending cap, in no year does the total of the anticipated revenue measures equal the level of the “New Revenue Measures” targeted in the 10-Year Plan.

Part of the reason for the shortfall is the anticipated proposed reduction in the corporate income tax. The obvious effect is to lower the deficit reduction achieved by the other measures. Even without that reduction, however, the Governor’s anticipated measures don’t total to the level of the “New Revenue Measures” included in the 10-Year Plan.

That is especially true of the years following FY2031, when the Governor reportedly will propose that the sales tax and the proposed increase in the minimum oil tax rate expire. In explaining the reason for setting those provisions for expiration, the Governor said during the week that, “The state will have ‘a difficult time with revenue’ for the coming five years, which will then be resolved thanks to new resource development projects… including a yet-to-be-finalized natural gas pipeline that is supported by President Donald Trump.”

The projection that the fiscal cavalry from “resource development” will arrive after five years is so speculative as to be reckless. The 10-Year Plan already includes anticipated production volumes and related revenues from the Willow and Pikka oil projects, the state’s two “new resource development projects,” which are projected to come online by the end of FY2031. To our knowledge, there are no other significant “resource development” projects projected to go online within that time frame that will add significant additional revenue.

And not only is the likelihood of the “yet-to-be-finalized natural gas pipeline” highly speculative at this point, but so is the level of its potential contribution to state revenues even if it is. The last estimate we saw of potential state revenues from the proposed Alaska Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) project was a one-page sheet included in a 2023 Alaska Gasline Development Corporation (AGDC) presentation. While the sheet stated that it was based on an April 2023 Department of Revenue analysis, we were never able to find the analysis to understand the assumptions underlying it.

Given its age and the significant changes in the global LNG market since then, we anticipate that at least some, if not most, of those assumptions are outdated. But even if not, the projected revenue levels for the FY2032 – 36 period are nowhere near sufficient to offset the expiration of the proposed sales tax and increased minimum oil tax, much less fill the additional shortfall beyond them.

The administration itself laid down the marker for the state’s revenue needs in its 10-Year Plan. Leaving those needs half-filled (or less) is not a complete fiscal plan.

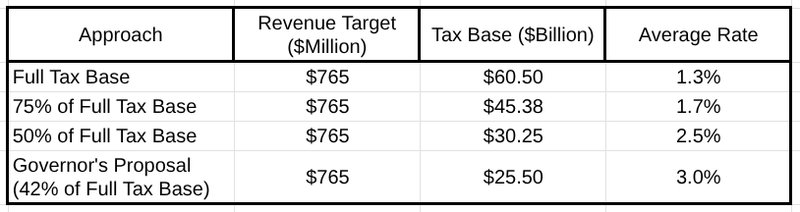

A second issue is that the anticipated sales tax rate appears far too high relative to the revenue it generates. Generally speaking, any state’s potential sales tax base is equal to its private-sector Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the total of all final private sector goods and services produced in the state. According to the most recent data from the Federal Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Alaska’s state GDP is currently around $60.5 billion.

On the other hand, doing the math, the Governor’s anticipated 2% – 4% seasonal rate (average annual 3%) implies that it is built on a tax base of only $25.5 billion ($765 million divided by 3%), significantly smaller than the state’s potential tax base and suggesting that it includes several significant explicit and implicit exemptions and exclusions.

A sales tax’s impact on taxpayers depends on its base. At a given level of revenue, the larger the base, the smaller the rate and the smaller the effect on any given taxpayer. On the other hand, the smaller the base, the higher the rate required to raise the same amount of revenue, and, with that, the larger the impact on the taxpayers it covers.

The relative size of the base also has distributional consequences. The smaller the base, the higher the rate, and the more regressive the impact. Conversely, the larger the base, the lower the rate, and the less regressive the effect.

Using the state’s full potential tax base as a starting point, here are some options for raising the same amount of revenue as reported for the Governor’s anticipated sales tax, using different bases. The tax rates are averages; they could be structured seasonally, as in the Governor’s approach.

If the goal is to raise $765 million annually, the rate could be reduced to as low as 1.3% by expanding the base to its full potential. The rate could still be kept below 2% by limiting exemptions and exclusions to a quarter of the full tax base (approximately $15 billion in goods and services). And the rate would still be limited to 2.5% even after exempting and excluding half of the potential tax base (approximately $30 billion in goods and services). The Governor’s anticipated proposed rate is higher only because the tax base it uses is significantly narrower.

We strongly encourage the Legislature, once it begins its review of the Governor’s proposals, to spend as much time examining the tax base underlying his proposed sales tax as any other aspect. Reducing the rate to lower the impact on Alaska families doesn’t require foregoing revenue. It can be accomplished just as easily by expanding the tax base to which it applies.

Our final, initial reaction relates to the changes to oil taxes anticipated to be proposed by the Governor. They don’t go nearly far enough.

As we have explained in a previous column, Alaska is projected to receive about 4% less as a share of gross wellhead revenue in the coming decade than it did in the last decade, the first under Senate Bill 21, the current oil tax code. In monetary terms, that’s an average annual shortfall of about $450 million. In addition, closing the so-called “Hilcorp Loophole” to the petroleum corporate income tax, which, as we have explained previously, is another needed fix to Alaska’s oil tax structure, would raise somewhere in the range of an additional $120 – 150 million annually.

Compared to the combined amount, the temporary change to the minimum tax rate anticipated to be proposed by the Governor raises only $155 million, or only about 25% of the needed adjustments, and even then, only for 5 years.

Part of the reason for the shortfall in revenue from the anticipated change to the minimum tax compared to past revenue levels is that, while the shift purports to raise the minimum tax rate to 6%, it doesn’t. As we explained in a previous column, the projected realized production tax rate is lower than the current minimum rate because rising volumes are qualifying for the Gross Value Reduction (GVR) credit. Because the GVR credits can be used to reduce a producer’s tax obligation below the so-called “minimum” rate, their growing significance is helping to drive the state’s overall realized production tax receipts well below the otherwise anticipated minimum.

Any change to the state’s oil tax structure proposing to raise significant revenue through increasing the so-called “minimum tax” should address this issue by also subjecting volumes qualifying for the GVR credit to the minimum tax. Otherwise, any gains anticipated from increasing the minimum tax will be significantly diluted as the volume qualifying for the GVR credit grows.

We look forward to providing additional analysis of the Governor’s proposed fiscal plan in future columns, once it is finalized. As we said, if he follows through on the reported proposals, he deserves credit for starting a conversation along realistic and needed lines. But his proposals will be only the start of the conversation. As we explained above, they will require work to build them into something that fully addresses, in the words of the administration’s own 10-Year Plan, “the stressed fiscal situation Alaska is in.”

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

A $1.5 billion shortfall, and still dancing around a $2.664 billion PFD feeding sprinkler? Outrageous. Just do away with the shortfall completely and send out a $1575 PFD. WTF? It isn’t rocket science.