Following the Legislature’s passage in 2013 of substantial revisions to Alaska’s oil production tax code (commonly referred to by its session bill number, “SB21”), Alaskans went to the polls the following year in a referendum election on whether to reject the revisions.

As many recall, one of the strongest arguments in support of preserving SB21 at the time was that the law would encourage increased investment, ultimately leading to more oil production and, with that production, more revenue for the state. That argument has continued to be used since, as a rebuttal whenever some have suggested changes in the approach. Indeed, as recently as earlier this year, in an op-ed in the Anchorage Daily News, so-called “Keep Alaska Competitive” co-chairs Joe Schierhorn and Jim Jansen claimed, “Over the next five or so years, new production will bring significant new revenue to state and local governments and maintain the viability of the Trans Alaska pipeline further into the future.”

As we explained in a previous column, however, that claim simply isn’t true. Over the next five years, and indeed throughout the entirety of the current ten-year forecast period used by the state, revenues from oil production are projected to decline significantly, even as production levels themselves rise dramatically. As we explained there:

Overall production in the 10-year period is projected to rise by an impressive 44%. Yet, production taxes are not anticipated to increase at that rate or even a fraction of it. Instead, production taxes during this period are projected to decline by 56%.

Some occasionally argue that the test isn’t whether production taxes alone increase, but whether total unrestricted petroleum revenue from all sources (petroleum property tax, petroleum corporate income tax, production tax, and oil and gas royalties) does. We disagree with that approach because the issue is whether changes in production taxes pay for themselves. Other factors drive changes in the revenues produced in other ways. Each source should be addressed on its own.

But even using that approach fails to demonstrate a gain in revenues. Using Fiscal Year (FY) 2024, the most recent year for which there is finalized data, as a baseline, the Department of Revenue’s (DOR) most recent revenue forecast (Spring 2025) shows that even as production volumes are projected to rise by 44%, total unrestricted petroleum revenue from all sources is projected to decline by over 25% (from $2.47 billion v. $1.97 billion).

The revenue decline is even worse when looking at the five years suggested by Schierhorn and Jansen. Using DOR’s projections for FY2030, production tax revenues are projected at only a third of FY2024 levels ($322 million v. $975 million), and total unrestricted petroleum revenue from all sources is only two-thirds of FY2024 levels ($1.65 billion v. $2.47 billion).

What is going on? Two recent DOR studies help identify the causes.

The first study updates DOR’s fiscal analysis of Santos’ Pikka project. The second does the same regarding Conoco’s Willow project. Both demonstrate the different ways in which the revenue levels from production taxes are being affected.

The Pikka analysis demonstrates the impact of developing a new field by a company not previously active in Alaska. Here is DOR’s explanation.

All costs incurred before production begins lead to reduced future state tax revenue, since losses can be carried forward and deducted against production tax accrued after production start-up. … [While production is scheduled to commence in FY2026], Production tax revenue begins in FY2034, other than Landowner Royalty Interest Tax (LRI) under AS 43.55.011(i) [applicable to the portion of production attributable to private lands].

Prior to this, production tax before LRI is reduced to zero by a combination of lease expenditure deductions, deduction of Carried Forward Annual Losses, GVR, and tax credits under AS 43.55.24(i) (for GVR-eligible oil). In FY2034, the project loses eligibility for GVR, so the remaining credits and deductions only reduce production tax before LRI as far as the minimum tax floor. In FY2039, remaining Carried Forward Annual Losses are insufficient to bring production tax to the minimum tax floor, and from FY2040 onwards, no Carried Forward Annual Losses remain.

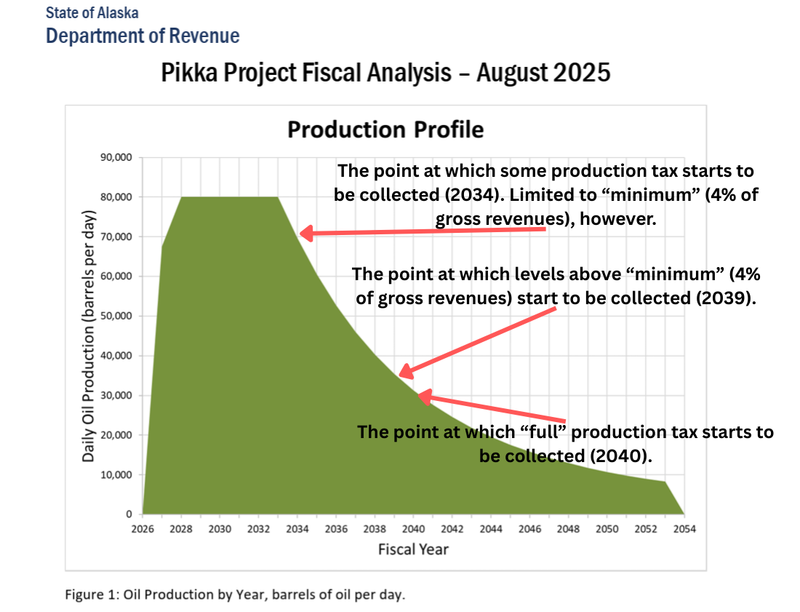

Here’s what that means in terms of points on the production curve, using the production profile included in DOR’s analysis.

Although the analysis projects first production in FY2026 and peak production from FY2028 through FY2033, no production taxes – not even the so-called “minimum” production tax of 4% of gross revenues – are collected until FY2034, seven years – and a significant amount of production – later. There is no make-up provision. Production taxes will never be recovered on the seven years of accumulated production.

The reason tax levels are reduced below the so-called “minimum” level (4% of gross revenues) and, indeed, to zero for the first seven years, is the provision in SB21 covering oil qualifying for the so-called Gross Value Reduction (GVR). As explained by DOR in the Fall 2024 Revenue Sources Book:

The gross value reduction (GVR) allows a company to exclude 20% or 30% of the gross value for that production from the tax calculation. Qualifying production includes areas surrounding a currently producing area that may not be otherwise commercial to develop, as well as certain new oil pools. Oil that qualifies for this GVR receives a flat $5 Per-Taxable-Barrel Credit rather than the sliding scale credit available for most other North Slope production. As a further incentive, this $5 Per-Taxable-Barrel Credit can be applied to reduce tax liability below the minimum tax floor assuming that the producer does not seek to apply any sliding scale credit. The GVR is only available for the first seven years of production ….

As DOR’s analysis indicates, even once production taxes start to be paid, they are projected to remain at the “minimum” level for another five years, until FY2029. Again, there is no make-up provision. The difference between full production taxes and the “minimums” will never be recovered on the additional five years of accumulated production.

Only once the GVR period expires and the previously accumulated Carried Forward Annual Losses are exhausted will “full” production taxes be realized by the state. DOR’s analysis, however, projects that this will not occur until sometime during FY2040, fourteen years after first production and at a point when roughly 75% of the projected volumes have been produced.

Even these projections may prove optimistic. As those who follow North Slope oil field developments are aware, Santos is already well into preparing for the so-called Pikka Phase 2 Project. Because under SB21, the oil tax credits generated by Phase 2 can be taken against Phase 1 production, “full” production taxes may not be realized until well beyond even FY2040. Indeed, as we will explain shortly occurs at Conoco’s Willow project, they may never be realized during the life of the field.

Separately, DOR’s Willow analysis demonstrates the impact of the development of a new field by a company already active in Alaska. The results are different from those at the Pikka project. Here is DOR’s explanation of Willow:

Before production begins, the development leads to reduced state tax revenue, since capital expenditures can be deducted against production tax accrued elsewhere on the North Slope. … Positive production tax impacts begin in FY2029, with the operator expected to pay below the minimum tax floor from FY2026 to FY2028 inclusive and at the minimum tax floor for the remainder of the analysis period.

As modeled, the operator does not enter an annual loss situation at any point for production tax purposes and therefore does not earn Carried Forward Annual Losses under AS 43.55.165(a)(3). If such losses were generated, they could be available as lease expenditure deductions against state production tax once the field begins production. In general, interaction between various components of the complex production tax system, including impacts of other investments and production, Gross Value Reduction (GVR), per taxable barrel credits, and the minimum tax floor, cause significant annual variation in production tax revenue. …

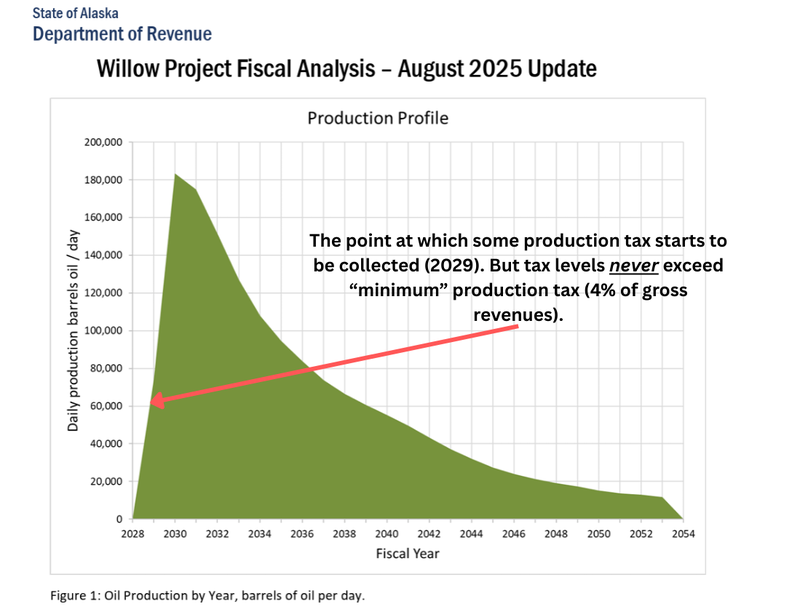

Here’s what that means in terms of points on the production curve, using the production profile included in DOR’s analysis.

The differences from Pikka largely relate to the fact that, as a company previously active in Alaska, Conoco has substantial ongoing production elsewhere on the North Slope. As a result, Conoco is able to utilize the type of credits and other deductions applied in the early years of Pikka, even earlier, to reduce its tax obligations in its other fields, even before beginning production from Willow.

It’s not that Conoco is receiving less benefit from Willow than Santos is from Pikka; it’s that Conoco is realizing the benefit earlier and across a broader volume than Santos. Indeed, a significant share of the reduction in production tax revenues reflected in DOR’s projections over the next several years, even before the start of Willow, is due to deductions for the expenditures being made at Willow.

Even once production taxes start to be paid, DOR projects that, due to ongoing activity within Willow and elsewhere, Conoco will remain at the minimum tax floor from FY2029 over the remaining 25 years included in its analysis. Production tax revenues from Willow will never rise above the “minimums,” and the difference between full production taxes and the “minimums” over the entirety of the production will never be recovered.

As we explained in an earlier column, SB21 is badly broken in the sense that state revenues from oil production aren’t increasing as production rises; indeed, state revenues are actually falling. We agree that the Alaska oil tax code should provide a sufficient incentive for the continued development of Alaska’s resources, but as the proponents of SB21 originally (and continue to) claim, Alaskans should share in the fiscal benefits of that development as it occurs. As production – and producer revenues – rise, so should Alaska’s revenues from that production. Alaska’s share should not be deferred until years later, or, as DOR’s analysis of Willow suggests (and as may occur also at Pikka as Phase 2 and other developments occur), to the point at which the state’s full share is never realized.

As we explained in another column, because these problems will only become bigger as additional fields are developed, the Legislature badly needs to fix production taxes now, before we continue to “drill, baby, drill.” Delay will only result in more and more production going untaxed, or taxed only at “minimums,” with the differences never recovered.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

ConocoPhillips is deducting willow project expenditures from their state production taxes even as the willow project is on federal land and the state stands to gain nary a dime in royalties from it.

Is it illegal to deduct costs from profits in state production tax law?

ALASKA HAS SO MUCH OIL AND GAS LOCKED UP WITH BAD POLICIES THAT RUN INVESTORS AWAY. THE TURNING POINT HAS TO COME SOON. TAPNOTTAX AND DRILL BABY DRILL, THE ROYALTY WILL MAKE UP FOR LESS TAX, LESS REGULATORY BURDENS AND LESS BONDS.

Ummm, Dan. There is no state royalty on production from federal lands, which is where most of the additional production comes from.