Readers of this column and other op-ed pages will know that the Legislature and others are in the midst of an intense debate over the structure of the Permanent Fund (Fund). Consistent with Article 9, Section 15 of the Alaska Constitution as currently written the Permanent Fund maintains a two-account structure, with the principal of the Fund (sometimes referred to as the corpus) held in one account, and the “income from the permanent fund” (sometimes referred to as the “earnings”) held in a second. By statute, the second account is called the “Earnings Reserve Account.”

Under the Constitution, withdrawals from the Fund are limited to the amounts maintained in the Earnings Reserve Account. The remainder of the Fund – the “principal” or the “corpus” – is off limits. Under the Constitution, that portion of the Fund “shall be used only for those income-producing investments specifically designated by law as eligible for permanent fund investments.” Those funds may not be used to supplement general fund revenue.

Some have proposed a constitutional amendment that would change that structure to provide for a single account, with an annual draw made from that account for the benefit of the general fund, regardless of whether the Permanent Fund is generating earnings sufficient to cover it. We and others have warned that such an approach could enable the withdrawal of funds which, under the current constitutional provision, are treated as part of the principal, potentially reducing the ongoing earning power of the Permanent Fund significantly.

Advocates of the change, on the other hand, argue that it is necessary to maintain a consistent flow of funds from the Permanent Fund to the general fund. They raise the concern that, absent the change, the Earnings Reserve Account may not contain sufficient funds to cover the annual percent of market value draw (POMV) on which the government is increasingly dependent to cover current spending. They argue that, depending on timing and size, such shortfalls could wreak havoc on the government budgeting process.

As we’ve explained in previous columns, we believe that preserving the corpus is of significantly higher priority than maintaining a consistent flow of funds from the Permanent Fund to the general fund. We also believe that changing the current two-account structure would undermine two important incentives that should strongly motivate the Permanent Fund Corporation (PFC), the manager of the Permanent Fund.

One incentive under the current structure is to minimize costs in order to maximize the level of earnings. The second incentive is to optimize returns, again to maximize the level of earnings. As we’ve explained in previous columns, we are concerned these incentives would be undermined if the Legislature is permitted to draw the same amount from the Permanent Fund regardless of the level of earnings it produces.

As the debate has continued, we have learned more about why some believe that, under the current structure, the Earnings Reserve Account may not contain sufficient funds in the future to cover the annual POMV draws. One involves some numbers that, thus far, have been missing from the debate.

In a recent column in the Alaska Beacon, Angela Rodell, a former CEO of the PFC, explained her view of the problem as this:

The formula allows for a 5% annual draw based on the average total market value of the entire fund — both the principal and the ERA. However, there’s a fundamental problem: While the draw is calculated using the full value of the fund, the money can only be taken from the ERA. The Legislature is legally prohibited from touching the principal, which means the full value of the fund is theoretical when it comes to actual cash available.

This creates an imbalance that threatens the very sustainability the Percent of Market Value system was designed to protect. Here’s why: Realized gains from investments, like selling a stock at profit, flow into the ERA, where they become available to spend. But unrealized gains — paper increases in asset values — primarily remain in the principal. The problem is that most of the fund’s growth has been in unrealized gains, which are locked away. Meanwhile, the Legislature continues to draw 5% of the average total fund value every year — but only from the ERA.

This means the ERA is being drawn down faster than it can be replenished.

On the surface, Rodell’s comments don’t make much sense. The specific problem she outlines – the lack of earnings converted to cash – wouldn’t disappear under a one-account structure. There would be as great a need for cash to fund the POMV draws under the one-account structure as under the two-account structure.

Either way, there is a need to convert as much earnings to cash as is required to fund the annual POMV draw. Because the cash would flow to the Earnings Reserve Account, that step would also solve the problem she identifies under the two-account structure. No constitutional change is needed.

Instead, what appears to be driving Rodell’s concern is a second issue she does not mention. Under the current structure, there are two cash calls on the Earnings Reserve Account. The first, as referenced by Rodell, is to fund the POMV. The second, under current law, is to fund what is called “inflation proofing.” In addition to the POMV draw, under AS 37.13.145(c), each year, “the corporation shall transfer from the earnings reserve account to the principal of the fund an amount sufficient to offset the effect of inflation on the principal of the fund during that fiscal year.”

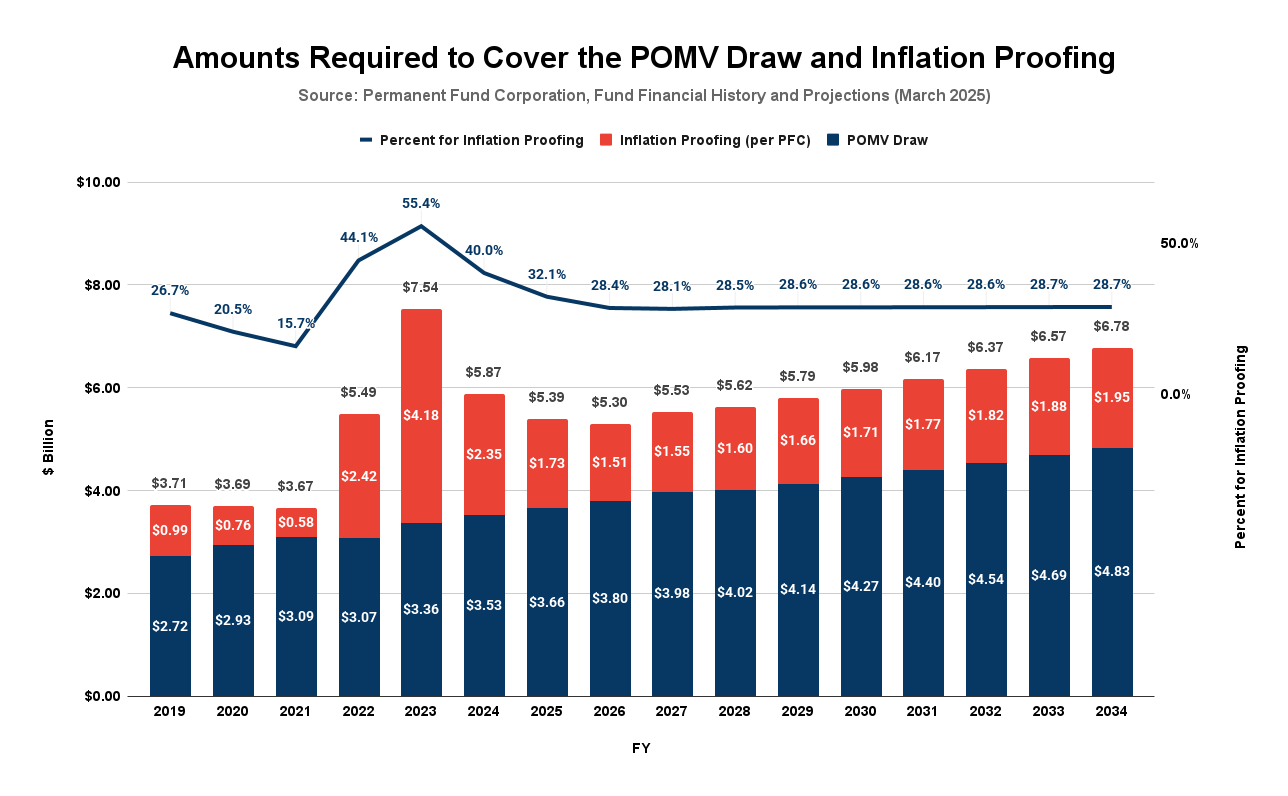

The combined effect of both cash calls is what appears to be threatening to overdraw the Earnings Reserve Account. The amounts required for inflation proofing are not trivial. Here are the past and projected amounts for each since Fiscal Year (FY) 2019, the first year of the POMV draw:

From FY19 through FY24, funding inflation proofing has required approximately $11.27 billion, or 37.6% of the total cash call on the Earnings Reserve Account. While the amounts are projected to decline over the remainder of the current forecast period (from FY25 through FY34), they are still projected to average roughly 29% of the total cash call over the period.

In theory, cash calls should not be a problem even at such levels. The PFC’s stated goal over time is to achieve a total return equal to the rate of inflation plus 5%. Because the POMV draw is also set at 5%, reaching the objective should produce sufficient funds to fund both the POMV draw and inflation proofing.

As we have discussed in previous columns, however, the PFC has not been achieving its objective in practice. Moreover, even when it has, the total return has not been realized in all cash. Instead, as Rodell’s piece references, a portion of the return has been in “unrealized gains – paper increases in asset values.” What is draining the Earnings Reserve Account is making a cash call at the levels required to cover both draws when the Fund has not been achieving returns at those levels, and even when it has, a portion of the return has not been in cash.

The second issue – that a portion of returns is not in cash – is easily handled, however, and does not require a revamp of the current Constitution. The POMV draw needs to be paid in cash because it is used, in turn, to pay out Permanent Fund Dividends (PFDs) and help cover the costs of government services. Both uses require cash.

While, historically, the amounts required for inflation proofing have also been paid in cash, there is no fundamental need to do so. Instead, they can be covered by crediting unrealized gains toward that obligation. Indeed, that is precisely what those proposing the constitutional amendment contemplate would happen under the one-account approach. The only cash required under that approach would be to cover the POMV draw. Inflation-proofing would be covered mostly, if not entirely, through asset appreciation.

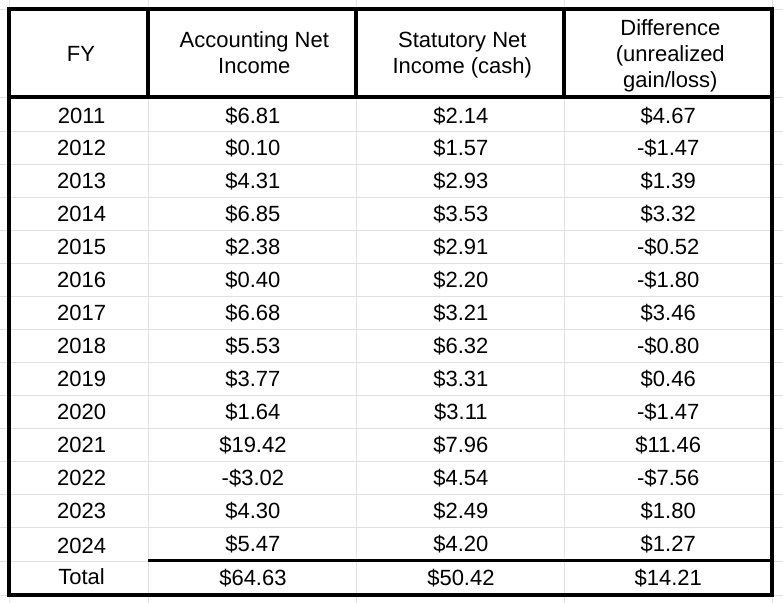

The division between the cash and non-cash portion of the annual returns can be visualized by looking at the difference between what the PFC reports for Statutory and Accounting Net Income. Statutory Net Income (SNI) is what the PFC receives in interest, dividends, real estate, and other income, plus realized gains (or losses) on the sale of assets, minus what it pays to cover operating expenses. Accounting Net Income reflects the sum of SNI plus unrealized gains (or losses) on invested assets.

In short, SNI reflects the portion of the Permanent Fund return realized in cash. The difference between Accounting Net Income and SNI reflects the portion of the Permanent Fund return realized in unrealized gains (or losses). As background, here are the annual amounts reported for those two sources by the PFC on its History & Projections reports from FY11 through FY24, the most recent available:

Over the period, the portion of the returns realized in cash has totaled $50.42 billion; the portion attributable to unrealized gains has totaled $14.21 billion, or 22% of the total.

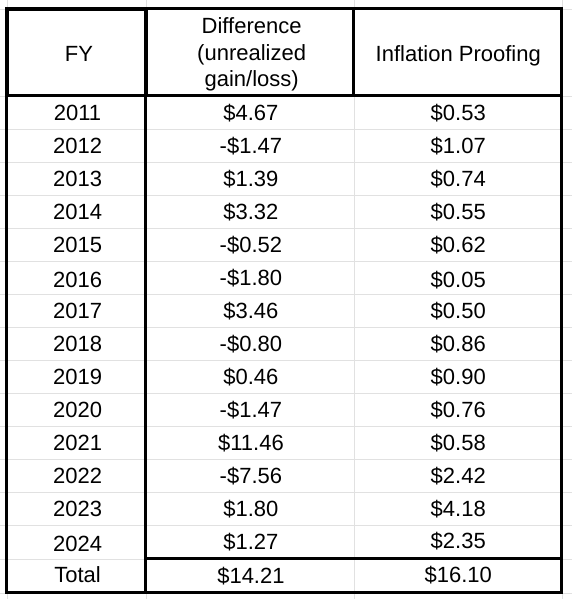

Again, using the amounts reported by the PFC on its History & Projections reports through FY24, here is the level of unrealized gains compared to the amounts required for inflation proofing over the same period:

While there are differences on a year-to-year basis, the overall totals are remarkably close. Over the period, the portion of the Permanent Fund returns recorded as unrealized gains equals nearly 90% of the amounts required for inflation proofing. If those had been credited toward the inflation-proofing obligation, only the difference, or roughly $1.9 billion, would have been required to be paid in cash. That would have amounted to less than 4% of the $50.4 billion in cash earnings realized over the period. The remainder would have been available to meet the draws required to be made in cash.

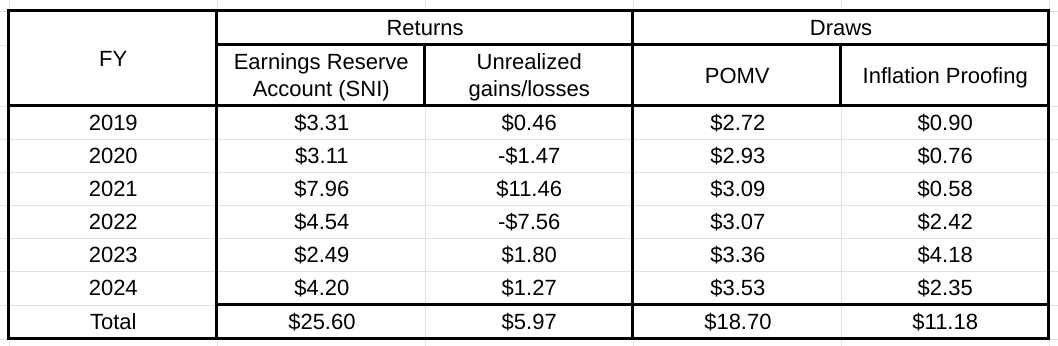

The following numbers focus specifically on the period since FY19, when POMV draws began:

Over the six year period, the amount earned by the Fund in cash ($25.6 billion) has more than exceeded the $18.7 billion required to cover the POMV draw. Despite bouncing up and down over the period, the amount earned by the Fund in unrealized gains has also ended up in the black and, if credited toward that purpose, would have covered more than half of the amount required for inflation proofing. The remainder required from the Earnings Reserve Account would have been limited.

The only reason the Earnings Reserve Account has declined over the period is that it has been used to cover both the POMV and inflation-proofing draws. If the unrealized gains had been credited toward inflation-proofing, the Earnings Reserve Account would have shown growth over the period.

In short, the concern that, under the current two-account system, the Earnings Reserve Account is in danger of being drained is hugely overblown. The Earnings Reserve Account has and is projected to continue to have enough cash to cover the POMV draw. The thing that is draining it is using it also to cover inflation proofing.

But the Earnings Reserve Account doesn’t need to be used for that. Because inflation-proofing is a non-cash requirement, the portion of the overall return arising from unrealized gains can – and should – be attributed to that purpose. Looking at the Fund’s history, such an approach would cover nearly all of the obligation.

The current two-account approach, which both fully protects the corpus and creates important incentives for strong PFC performance, does not need to be – and, as a consequence, should not be – changed for that or any other reason.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

You can’t have $81billion sitting there without the vultures and other scavengers fighting to get their teeth into it. It’s really that simple. When it’s gone, they’ll disappear.

Thank you for illuminating the interplay between “market value” and cash requirements. Much appreciated.

Thank you to Brad Keithley for this thoughtful and important analysis. It should be mandatory reading for all Alaskan leaders. During my 16 years as a legislator, we always honored the statutory dividend formula. We also honored the constitutional budget reserve three-quarter vote requirement to balance the budget. As Co-chair of the Senate Finance Committee in charge of the Operating Budget (one of the lowest per capita spending budgets in state history) I spend a huge amount of time, starting at the very beginning of sessions, working with minority leadership and individual members to achieve that three-quarters vote to adopt… Read more »