This week we take a first look at Governor Mike Dunleavy’s (R – Alaska) proposed FY23 budget in an effort to establish a baseline for future discussions about it on these pages and elsewhere.

While others tend to start similar reviews by diving deeply into the budget covering the next immediate fiscal year, our initial look normally focuses more on the 10-year Plan required to be published as part of each budget cycle. That perspective enables us to evaluate whether the proposed budget, in fact, is “sustainable” over the long term, or just another in what seems, over the past decade, to have become an endless stream of one-off “fiscal plans” relying on various budget gimmicks just to get through another year.

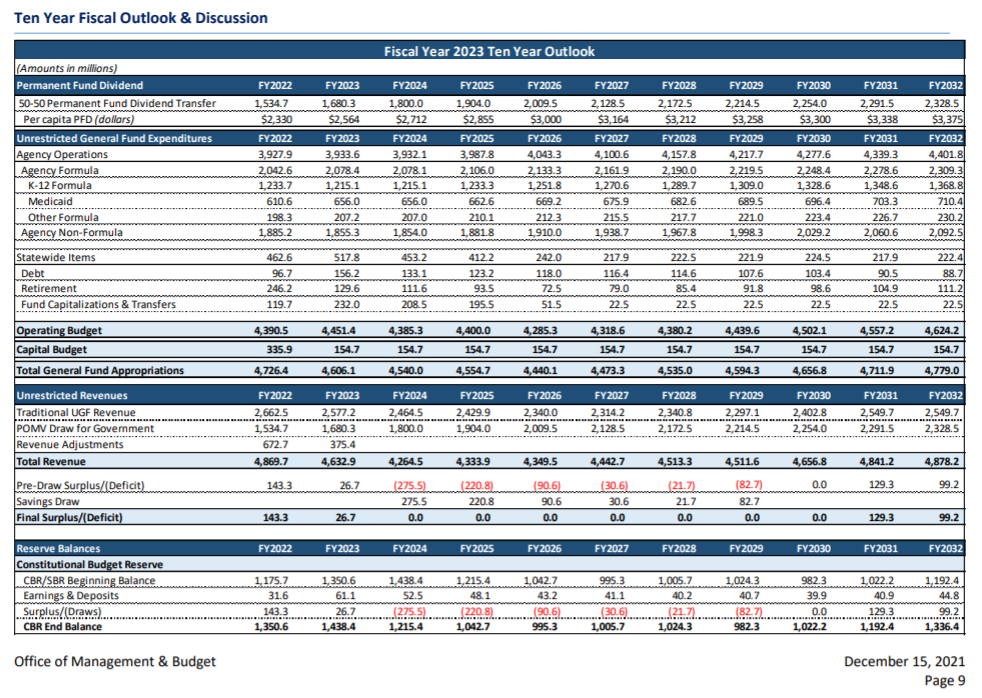

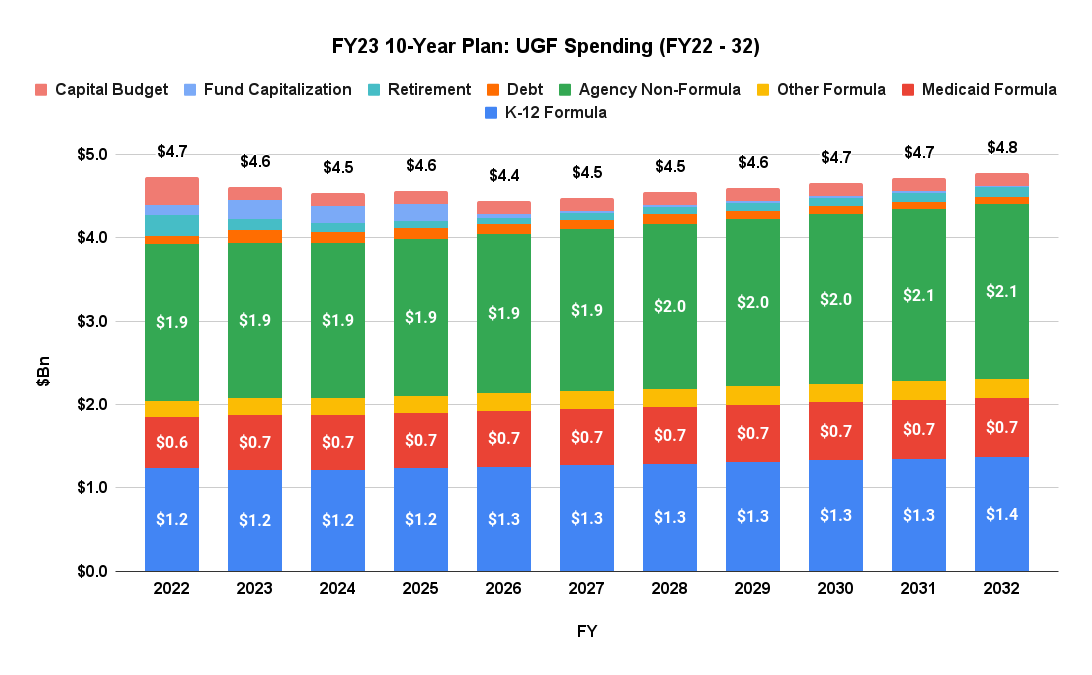

This is the Administration’s proposed FY23 10-year Plan.

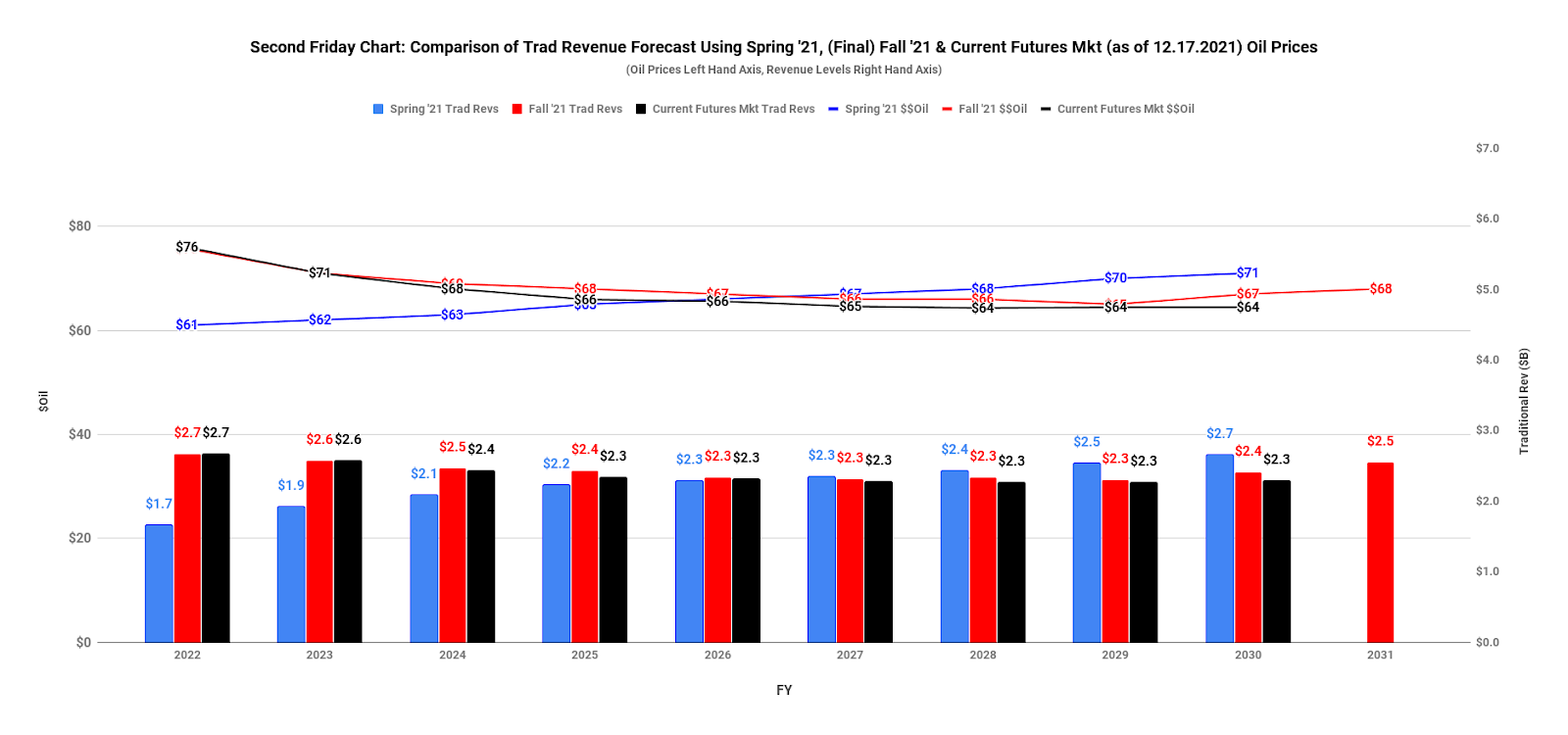

This year we started our review with the oil revenue projections, which in turn are based on the projections contained in the Department of Revenue’s Fall 2021 Revenue Sources Book.

We started with these because, as we explained in a previous column, we had serious problems with the oil revenue projections contained in the Administration’s previous, Preliminary Fall 2021 Revenue Forecast (Preliminary Forecast) published to some public relations fanfare at the end of October. While the Preliminary Forecast used then-current futures prices as the basis for the first two years of its projection, the prices used for subsequent years were derived arbitrarily by escalating the previous year for inflation. The result varied significantly from the prices for the corresponding period reflected in the futures market, substantially overstating market-based revenue projections.

The FY23 10-year Plan mostly corrects for that, using futures prices current as of the date of its publication as the basis for all of the years for which prices for Brent futures are available on the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), Brent’s most widely traded platform. Only the last three years of the forecast, FY30, 31 and 32 – years for which there are as yet no futures contracts on ICE – continue to use the inflation adjustment technique. At least as of last Friday – when we normally do our weekly comparison of market prices against forecast – the traditional revenues reflected in the Plan generally track the market as far as it goes

Of course, as we discussed in another previous column, oil prices aren’t the only factor involved in determining oil revenues. Production levels also play a role. Given the current level of Conoco’s activity on the Western North Slope, at first blush we don’t find the Administration’s projections in the FY23 10-year Plan out of line, but will have more to say about those in a subsequent column.

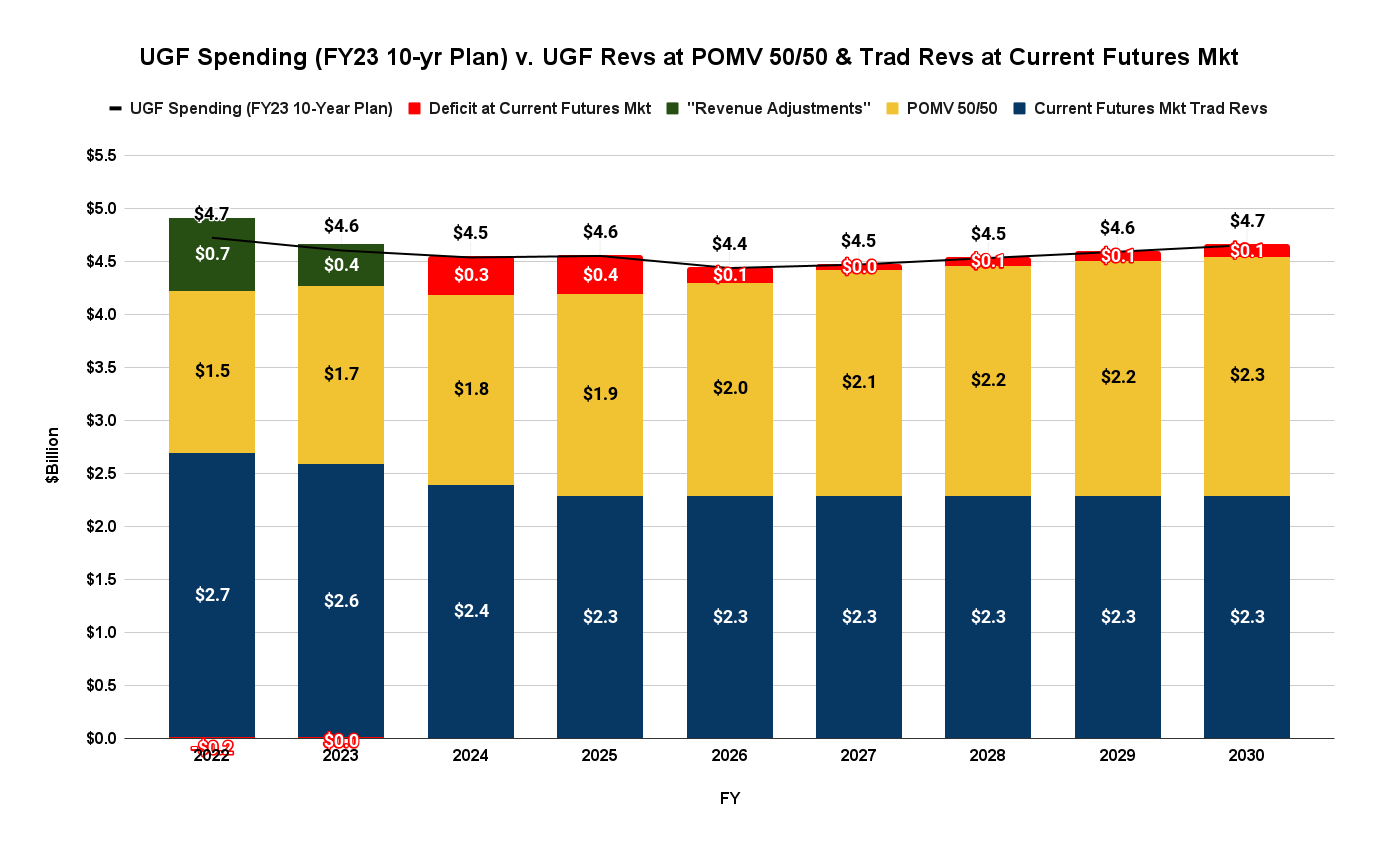

While oil revenues are significant, they are not the only source of revenue. The FY23 10-year plan also includes revenues projected to be available from the POMV draw (after deducting the Governor’s proposed POMV 50/50 PFD) and, for FY22 and 23, “federal COVID-19 relief funds designed to replace unrestricted general fund revenue.”

We layer those on top of traditional revenues calculated at current futures market price levels, here:

We generally agree with the projections of these components. At first glance the POMV draw appears to be consistent with the Permanent Fund’s most recent projections over the same period (which in turn are based on “2021 Callan capital market assumptions and median expected returns (the mid case)”) and while some will argue with the manner in which the unrestricted federal funds are spent, they are, in fact, available to help support the UGF budget.

Even on its face, however, the Administration’s FY23 10-year Plan is not sustainable, in the sense that projected long-term revenues are sufficient to cover projected long-term spending.

By relying on CBR draws to balance, the FY23 10-year Plan itself admits that projected revenues don’t meet projected spending levels from the expiration of unrestricted federal support in FY23 through FY29. And the deficits for FY24-27 would be even deeper if the $200 million projected as the “State match” for the additional funds anticipated to be received from the recent federal infrastructure bill (mentioned in the last sentence of the text on “Capital Investments”) were included in the calculations.

On top of that, the balance shown in FY30, and slight surpluses in FY31 and 32 are due only to applying an upward inflation adjustment to the price of oil. If, instead, the price of oil was held to the trendline derived from the years prior, a common technique for projecting prices beyond the end of a published series and one we use in calculating the projected price for FY30 in the chart above, even the surpluses turn to slight deficits.

The Administration attempts to gloss over these continuing deficits by arguing that “the CBR [Constitutional Budget Reserve] is projected to have a balance healthy enough to bridge short-term revenue shortfalls for the foreseeable future.”

But even if that is the case in the near term, running continual, year-after-year deficits is not sustainable over the long term and, as importantly, does not leave future generations at anywhere near the same savings levels this generation has consumed over the last decade. That not only fails the age-old admonition that each generation should leave future generations at least no worse off than the situation passed on to them from prior generations, it also is inconsistent with Art. 9, Section 17(d) of the Constitution – which contemplates that withdrawals from the CBR ultimately are to be paid back.

But these facial problems with sustainability pale in comparison to those that arise once we start digging into the spending levels proposed in the Plan.

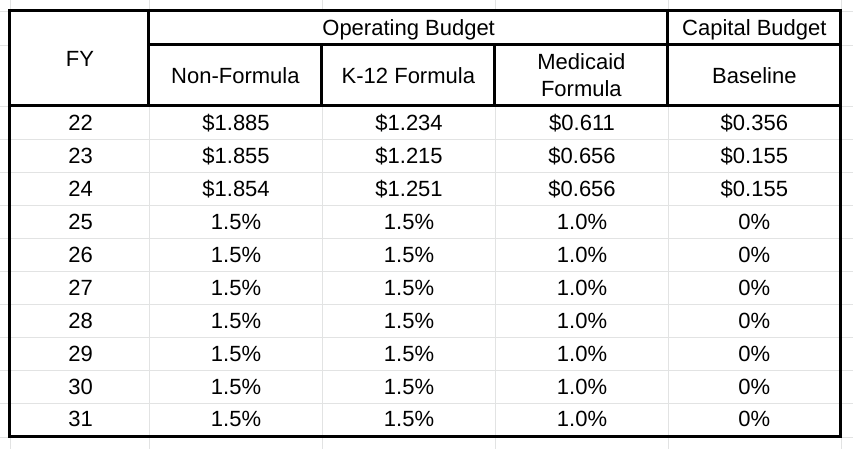

The method the Administration uses to make the FY23 10-year Plan even approach balance is to significantly suppress projected future spending levels. Attempting to overcome the problems the Administration encountered in 2019 when it advanced deep spending cuts, the FY23 10-year Plan instead proposes to achieve long-term balance by assuming very low rates of growth for most spending categories, and then only after holding spending flat through FY24.

Walking through the FY23 10-year Plan reveals the following annual adjustment factors underlying the major spending categories:

Combined with lower “Statewide” costs largely driven by changes in the amortization of retirement costs and the final payout of reimbursable oil tax credits, the overall result of these ultra-low growth rates is to limit the overall change in UGF spending from FY22 ($4.73 billion) through FY32 ($4.78 billion) to only about $50 million, or 1%. On an annualized basis, that’s an annual growth rate throughout the entire 10-year period of only 0.1%.

Compared to the current general inflation rate of roughly 7% and even the long term Fed “average inflation target” of 2% (also used in the Callan projections for the PFC), sustaining such a low overall growth rate over an entire decade is highly implausible, especially since the Administration does not appear to propose to make any changes in the underlying statutes that help drive spending growth.

Even adjusting the Administration’s proposed FY23 spending levels to a still low 1% annual growth rate, spending would reach $5.1 billion by FY30, resulting in a deficit against projected revenues of $400 million.

Looking at the Administration’s prior track record on such forecasts only confirms the implausibility of the forward spending levels projected in the FY23 10-year Plan.

In its FY20 10-year Plan, for example, the Administration projected FY22 UGF spending of $3.93 billion. In its FY21 and 22 10-year plans, it adjusted that to $4.04 and $4.31 billion, respectively. Now that we are there, however, and the Administration is confronting reality, it projects FY22 spending at $4.73 billion, fully 20%, 17% and 10%, respectively, higher than its previous projections.

Of course, the reason the Administration isn’t more realistic about future spending levels is because it wants to avoid discussing how it proposes to pay for them. But pretending the elephant in the room doesn’t exist doesn’t make it go away.

Instead, by failing to propose alternative revenues to address these likely long-term budget shortfalls, what the Administration implicitly is setting up is a continuation of the ongoing experience of the last several years – ever deepening PFD cuts, the alternative that has the “largest adverse impact” on 80% of Alaska families and the overall Alaska economy. As we have seen over the last five years, failing to develop a more equitable, lower impact alternative leads to continued PFD cuts by default. The Administration may say it wants a “full” PFD, but it isn’t taking the necessary steps to achieve it.

As readers of our previous columns might expect, we have some problems with that. As a result, in future columns we will continue to look at various aspects of the Administration’s proposed FY23 budget, including its impact on the overall Alaska economy and Alaska families, and various alternatives to better position Alaska going forward.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

We can never admit that a “non-renewable” resource (like oil) eventually is depleted nor that our primary source of revenue is now the return to the Permanent fund. What a great time to fire the very successfully fund manager to avenge another Dunleavy vendetta. And perish the thought that we might means test the PFD. What will have the “largest adverse impact” on 80% of Alaska families and the overall Alaska economy” is the complete erosion of the ability to build, let alone sustain, our infrastructure and social safety net apparently so that Mike Dunleavy and others in his income… Read more »

While we’re thinking about means testing the PFD, let’s consider means testing the tax-free services that come from the same source. Our collective insistence that our only possible sources of major revenue are oil and Permanent Fund earnings is absurd.

We need to focus on the spending side of the budget, not revenue. There are so many ingrained expenditures that are supported politically by interest groups, that I really don’t know how we can solve our budget problem. Many of these programs create additional program spending. We have literally created spending that has created social problems that then create more social program spending. Take “Homelessness,” We have spending programs that are already creating the next generation of homeless. There are no efforts to deal with root causes or to eliminate homelessness…only to throw money at symptoms. …no political will to… Read more »

Anchorage’s homeless population has not changed significantly in the last 10 years,how to manage costs are changing. As our population ages how to address mental and physical health issues will require spending some money. The social conservative model of private faith based care is woefully inadequate

David, it sounds like you’ve spent too much time listening to pundits who get paid to make stuff up with the goal of pissing people off. (Hey, it’s a job.) If you’re truly interested in homelessness, you might acquaint yourself with the work of the Anchorage Coalition to End Homelessness. They are definitely making an effort to deal with the root causes of homelessness using solid data and evidence. But prepare yourself to be shocked. The causes are myriad and complicated, and not what your post suggests you might think they are. 70% of state services & infrastructure are funded… Read more »