Sometimes the inspiration for these weekly columns comes from comments made by readers. This week’s column is one of those.

In response to our column last week, one reader said this:

Everyone seems to miss the obvious. There will be at least 400,000 barrels of oil per day MORE coming through the pipeline over the next few years. There will be plenty of revenue for government expenses without the need for taxes.

While optimism is always welcome, this seems highly excessive.

As we discuss further below, the projection of an additional 400 MBD (thousand barrels per day) from the North Slope “over the next few years” significantly outstrips the projections made by the Departments of Revenue (DOR) and Natural Resources (DNR) in their most recent, Fall 2021 Revenue Sources Book and Spring 2022 Revenue Forecast. Combined, those agencies not only seem to be in the best position to assess future production levels, they have, if anything, a strong incentive to err on the high side. And their current projections reflect far lower volumes.

Moreover, last month highly regarded oil industry analysts Wood Mackenzie published a new report focused on where the oil industry is headed globally: Energy super basins: Where the renewable, CCS and upstream stars align. In that report, WoodMac had this to say specifically about Alaska, which tends to move things even lower down the optimism scale:

Hard-to-decarbonise basins likely to be left behind

Some of the traditional super basins are not well placed for a more sustainable future. Their paucity of renewables and limited CCS potential will cause investment to fall and the corporate landscape to shrink, especially under our AET-1.5 scenario.

Larger disadvantaged examples include West Siberia, most other Russian basins, Venezuela, Alaska and parts of Central Asia. Here, the high cost of renewables and/or limited access to these technologies are the main problems. Many smaller basins in Southeast Asia are also challenged.

Disadvantaged basins face a flight of capital and a product that is harder to sell as consumers increasingly shun high-carbon options. The leading international oil companies will be among the first investors to leave. Some national oil companies and private firms with less onerous emissions targets may be happy to pick up any opportunities left behind. But the writing is on the wall. All companies must eventually back away from higher-carbon resources.

Host governments may try a range of different incentives in a bid to stem the tide. Fiscal terms, regulation and policy must all work to optimise the integration of upstream, CCS and renewables as far as possible. But unless governments can address the underlying issues, they will face growing political and social resistance to any attempts to prolong the life of high-carbon basins.

The reader’s comment, however, did make us curious about how much additional production would be required to balance the budget over the next decade without the need for additional revenues.

It’s a lot.

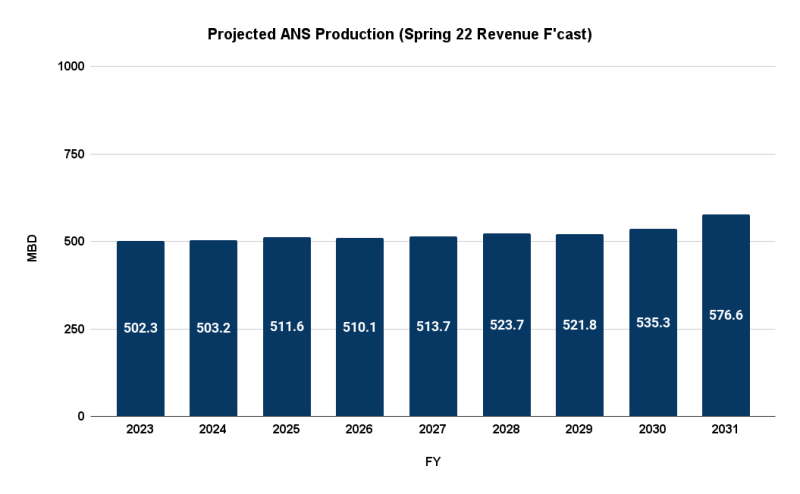

Here’s the projected production levels included in DOR/DNR’s most recent forecast.

According to the more detailed field analysis included in DOR/DNR’s similar, Fall 2021 projection, by 2031 roughly 140 MBD – or 25% – of production already is projected to come from “projects under development and under evaluation that are outside of [existing] areas, including Alkaid, Guitar, Narwhal, Pikka, Placer, Smith Bay.”

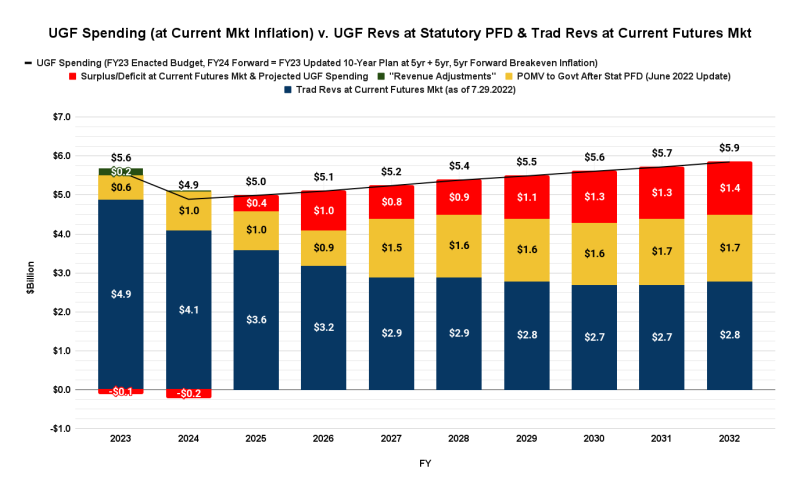

At those projected production levels – and using the most recent oil future prices – here is what the outlook for the “current law” (statutory Permanent Fund Dividend) budget looks like over the same span, using our most recent “Goldilocks charts”:

At currently projected revenue and spending levels, deficits (red, at the top of the bars) begin in FY 2026 and build throughout the remainder of the current decade and beyond.

So, what additional production levels would be required to close those deficits.

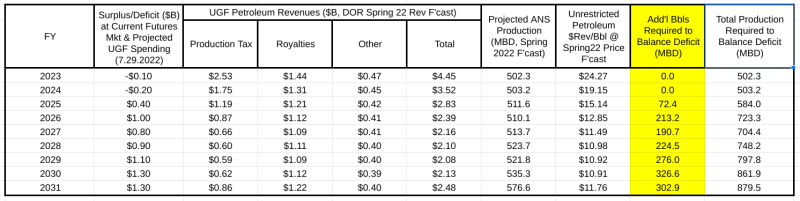

A baseline for the levels can be roughly estimated by calculating the per barrel amount projected in the Spring 2022 Revenue Forecast to be received by the state as unrestricted revenue over the relevant period and then dividing that into the deficits projected above.

Here’s the calculation:

(For those wanting to pop out an enlarged version of the chart, go to this August 5, 2022, column on our Substack page.)

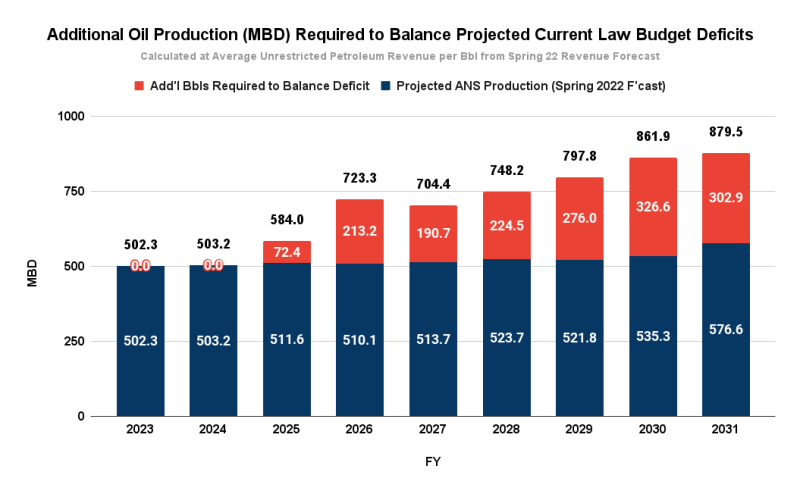

Or, put in summary chart format, this:

In order to offset projected deficits by FY2031, baseline production volumes would need to increase over currently projected levels by roughly 303 MBD. And that is in addition to the 140 MBD from “projects under development and under evaluation that are outside of [existing] areas” already included in DOR/DNR’s base amount. Combined, those two categories represent more than 50% of what FY2031 production would need to be.

Even to offset projected deficits in FY2026 – just three years from now – baseline production volumes would need to increase over currently projected levels by roughly 213 MBD, or slightly more than 40%.

And the actual, additional volumes would likely need to be even more.

The use of the “unrestricted petroleum revenue per barrel” in the calculation above assumes the additional volumes would reflect the same split among federal, state and new production as projected to be realized at the levels included in DOR/DNR’s Spring 2022 Forecast.

Because federal volumes do not generate royalty for the state, and new volumes qualifying for a “Gross Value Reduction” (GVR) under the state’s oil tax code pay a lower production tax rate, a heavier share of those components in the additional volumes would reduce the overall revenue received from them by the state.

Because a significant share of any increase in production above the levels projected by DOR/DNR would likely come from federal lands, new production qualifying for the GVR reduction or both (new production from federal lands), the “revenue per barrel” generated by the additional barrels likely would be materially less and thus, even more production would be required to produce the level of additional revenue required to close the projected deficits.

Certainly, increased volumes – and increased revenues at whatever level – are welcome. But the question is whether those additional volumes are sufficiently realistic to be relied on for fiscal planning purposes.

As we explained in a previous column, over the past decade Alaska has used up most of its fiscal reserves (the Statutory and Constitutional Budget Reserves), to paraphrase Samuel Beckett, “waiting for the Godot” of one or more of spending cuts, increased production or a long-term, sustained increase in oil prices. Like Beckett’s Godot, none of those have arrived, and as we explain in the column, if anything, Alaska now needs to be refilling its fiscal reserves, not relying on them even further as back up in the event overly optimistic production projections fail to come to fruition.

As a result, there is very little, if any, margin for error remaining in the state’s fiscal planning process. The state needs to be relatively secure that any additional production volumes are likely to be there before staking its fiscal future on them.

To be blunt, given DOR/DNR’s own outlook and the additional concerns resulting from the Wood Mackenzie report, deferring other fiscal steps waiting on an additional 400 MBD “ship” to come in is irresponsible. Not only does it require having faith that an additional 302 MBD, on top of the already projected 140 MBD – or combined, roughly an additional 90% of current production levels – will be flowing by FY 2031 (i.e., in eight years), to avoid building up deficits in the meantime it requires nearly half of that (213 MBD) to begin flowing in the next three years alone.

No one should take that bet.

In the previous column to which the comment we discuss here was made we explained why taxes were a better fiscal option for both 80% of Alaska families and the overall Alaska economy than continued PFD cuts. The comment didn’t take issue with that, but rather argued that presumably neither is needed in view of the coming production increases.

If the production levels predicted in the comment – and related revenues – materialize it will be easy enough at that point to reduce or eliminate any taxes adopted in the meantime. But if they don’t, without adopting lower impact, more equitable alternatives in the interim, the only realistic option available to offset continued deficits will be continued, deep PFD cuts, just as has happened the past seven years.

In short, middle and lower income Alaska families and the overall Alaska economy will continue to bear the brunt of interminably – and likely again unsuccessfully – waiting on yet another fiscal “Godot.”

As we said above, any increased volumes and revenues are more than welcome. Indeed, we hope they happen.

But middle and lower income Alaska families, as well as the overall Alaska economy, shouldn’t be left twisting in the wind waiting for them to arrive.

Brad Keithley is the Managing Director of Alaskans for Sustainable Budgets, a project focused on developing and advocating for economically robust and durable state fiscal policies. You can follow the work of the project on its website, at @AK4SB on Twitter, on its Facebook page or by subscribing to its weekly podcast on Substack.

If the State needs to generate about $1.4 billion in annual revenue, it could institute a flat 8.5% income tax on the first $50,000 earned. A regressive tax that puts all the burden of paying for State services on the bottom half of earners would get rid of the pretense that any politician cares a rat’s ass about anything other than enriching themselves. The Federal Government just passed a bill that gives $52 billion in corporate welfare plus another $25 billion in tax credits to Corporations like Intel ($19 billion in annual net profit) and Qualcomm ($12 billion in annual… Read more »

Hmmm, just ballparking, but the regressive slope of that tax wouldn’t be far off what we see with PFD cuts. That may be something to explore in a future column to help continue to drive the point home about the extreme regressivity of of PFD cuts.

We need a flat tax on ALL personal / household income. Above Eric suggested only taxing the first $50K of income letting those that make more not paying the same % as low income workers. I believe we should tax everyone at the same rate. I’m not sure what that flat tax # should be. In the past I have been told 5%, however state spending has gone up since then so the tax may need to be higher just to maintain current spending levels.